The patrimonial value given to ruins: the unusual, vaguely explained, and hardly registered constellation of architectural behemoths that are sprinkled through Sicily may be hardly prized, yet a new art project seeks to bring them into the fold. “Incompiuto Siciliano”, a rather tongue-in-cheek title in the naming convention of architecture and its pantheon, is the name given to these incomplete buildings, nearly 350 of them.

Financial boondoggles of official and unofficial corruption during the last half-century or so, 160 of them are in Sicily, these incomplete water towers, hospitals, sports centers, and recreational building projects that rewarded those who conceived of them and washed money with them.

Quizzically they dot the countryside, giving communities colorful and incomplete stories to tell, and they may not contribute to history in the same manner as more famous structures that the country is known internationally for.

Now a public art project seeking to adopt these orphaned buildings, the organizers of the “Incompiuto Siciliano” (Incomplete Sicilian) project say they are locating, registering, studying, and preserving them. Now they seek to regale these empty shells, these brutalist towers in the rolling green, and welcome them into communities.

Calling upon the calligraphic prowess and the talent for the written word of the Mexican painter Said Dokins, organizers say he was asked to intervene, conclude, or redefine one of these incomplete buildings. Today we bring you his exhausting works that cover the outward-facing visages of this confrontational arrangement of modern century fragmentation.

“It is made up of four Kubrickian monoliths that form a cross, but that represents a trick, a whirlwind of power, money, and politics,” says the press release. Never functional, they are nonetheless structural. By delving into the area’s history and that of Trapani, a small city on this Italian island of Sicily, Said creates his own complex tribute.

Below the images are descriptions of the project provided by the artist.

Part – 1 The Prisoner

The “X”, conformed by gold and silver letters on a deep greenback, is presented as a symbol of cancellation, a way to cross out the logic of Incompiuto, through the re-writing of two ancient texts where the political language expands across time. The first one is the heartfelt call of a trapanese prisoner in Tunisia. It’s the last letter from Alberto Gaetani to his sister, dated in 1776, asking her to intercede for his life so he could go back home. The second text is a Trapanese Facio Communist manifesto, in which they described the rights workers should have access to. Their revolutionary demand, without a doubt, resists all that the Incompiuto stands for.

Part – 2 The Dialectal Poet Of Trapani

Dokins takes the words from the Trapanese poet, Giuseppe Marco Calvino, bringing to our time his poem “U seculu decimu nonu“, a sharp critic on power abuse released more than 200 years ago. The artist plays with the contrast between the monumentality of his calligraphy in white and gold, which attributes to the text a sense of dignity and a voice of authority denied to the popular language used to write this poem, originally in Trapanese dialect.

Part – 3 The Slaves

The artist takes a series of writings from the 18th century that contains a list of names, along with their physical characteristics and the work they did. It was a slave inventory. Dokins rewrites those names, making them appear in some sort of binnacle, a huge reticular design that resembles the motherboard of a computer, refer to the new cataloging and control systems, new ways to perpetuate the slavery logic in contemporary social relations.

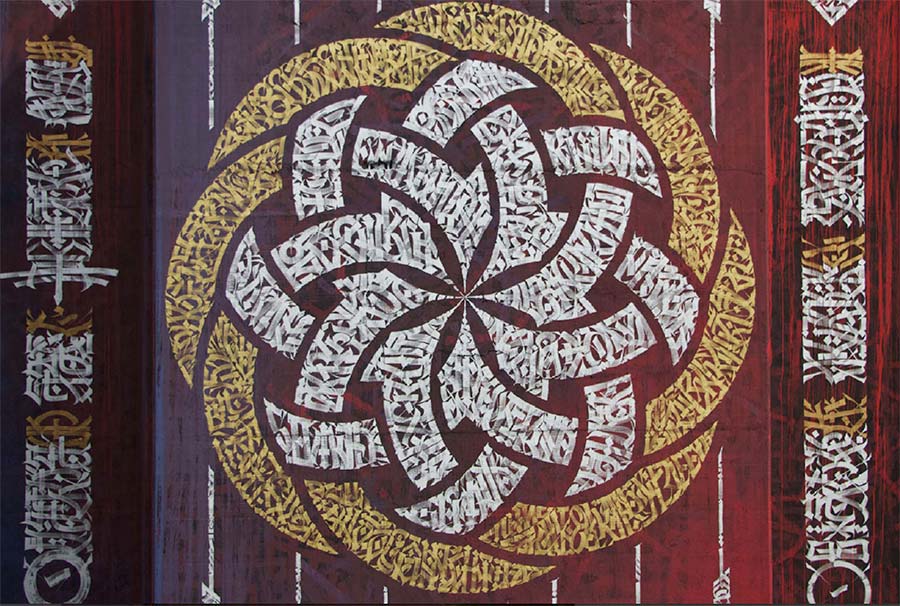

Part – 4 The Rose Window

Through the stylization of the iconic rose window of the church of Sant Agostino in Trapani, where symbolic elements of the three principal monotheist religions – Catholicism, Judaism, and Islam- can be found coexisting in the same sanctuary, Said Dokins turns the profane, an abandoned concrete wall, in a sacred place. The juxtaposition of traditions and cults reflected in the rose window, it’s an example of the cultural diversity that converges in the Sicilian territory, with its tensions and clash. The composition is constructed by the repetition of the sentence: “Everywhere I write is a sacred place”. Writing becomes a ritual act that serves the artist to dislocate the separation between the sacred and the earthly.

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY