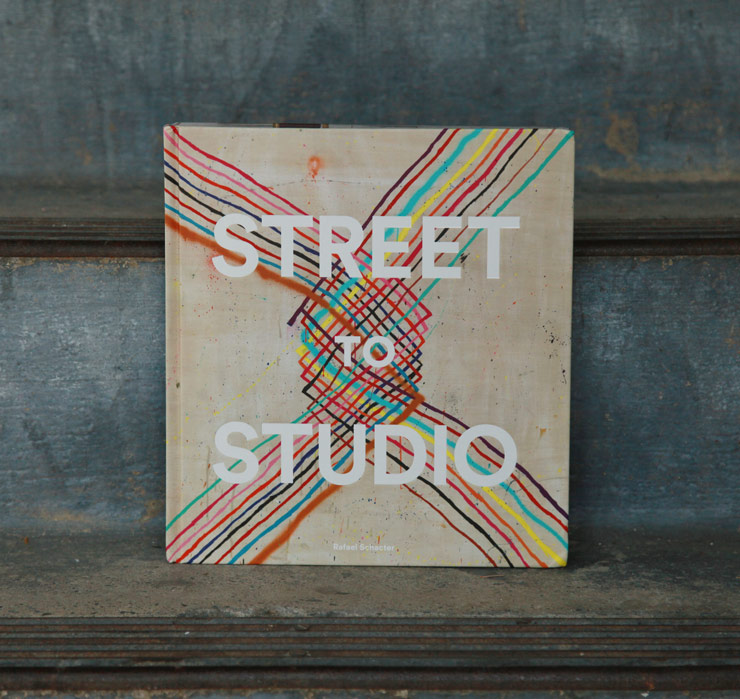

“These are artists who are thus not slavishly reproducing their exterior practice within an interior realm but who are, rather, taking the essence of graffiti – its visual principles, its spatial structures, its technical methods, its entrenched ethics – and reinterpreting them with the studio domain,” says author Rafael Schacter in his introductory exposition for his book Street to Studio where he offers a unique assessment derived from his 10 years of researching the foundational, conceptual, methodological, and ethical considerations that impact the original graffiti/Street Art scene as well as where it is going.

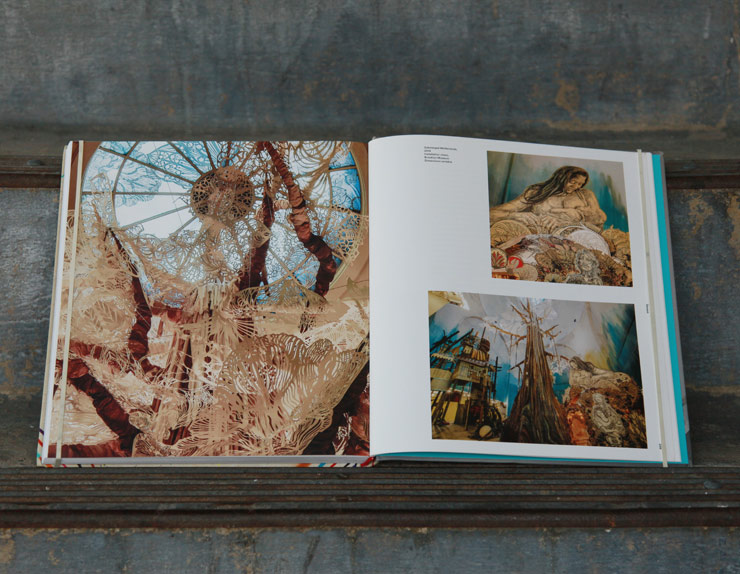

Rafael Schacter. Street To Studio. Lund Humphries Publishers. London, 2018.

The presentation is impressive in the craft and depth of field; the 40 artists whom he has chosen to profile have elements of each of these considerations to one degree or another as they move from street culture to more formalized ways of analyzing their works. Whether figurative, conceptual, performative, iterative, abstract, ephemeral, or purely digital, Schacter endeavors to find a common thread in a wide field of work and influences that have as their common denominator a regard for the practices of art in the streets.

It may be difficult for some readers to see the streets from here; perhaps it is not a measurement of relative biographies or works through storytelling as much as it is an examination of methods and practices. Often it could appear to be a name-checking of alliances with recognized contemporary artists, schools of art practice, and an anchoring to experiences as student of formalized institutional structures rather than the streets that help define the artists – criterion which ironically have been used to bar consideration of many early graffiti writers as relevant artists, with the effect of stigmatizing them.

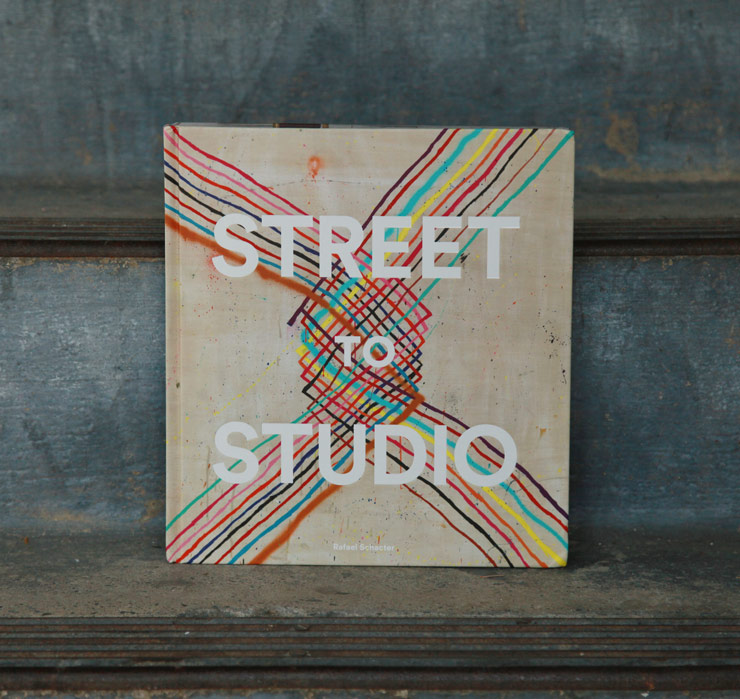

Rafael Schacter. Street To Studio. Kaws. Lund Humphries Publishers. London, 2018.

There are not stories of economic or structural adversity here – although one can argue that these may be equally formative realities that affect one’s art practice. You won’t find many references to attending Public School 141 or the local community college or working as a bike messenger.

Instead there are many finely educated artists here with backgrounds in formal art theories – an MA in Fine Art at Central Saint Martins, an MFA at Universität der Künste Berlin, or London’s Central Saint Martins, Oslo’s National Academy of Art, Paris’ Saint Denis or Madrid’s Complutense. Being a part of the Mission School of 1990s San Francisco is what helps ratify a work as Fine Art, for example, even though switching the nameplates next to certain pieces may cause you to place the work in a number of possible categories or potential origin.

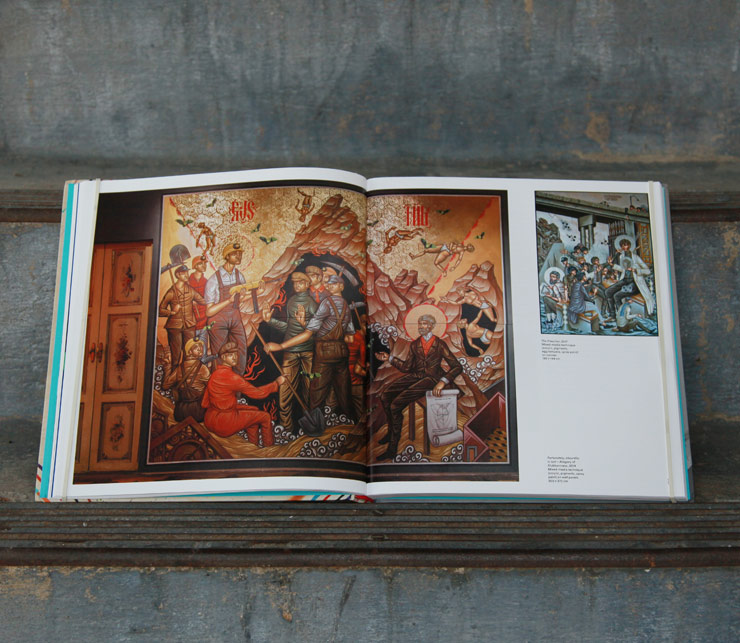

Rafael Schacter. Street To Studio. Stelios Faitakis. Lund Humphries Publishers. London, 2018.

The inclusion or exclusion of specific details in an artists journey or resume is the authors prerogative and is in service of supporting a view of the work. As part of our daily discourse where we receive texts from artists, PR folks, and historians, we enjoy listening to how people and their art are described by themselves and others; what cultural signifiers are used, what associative “branding” is employed, and to note the differences that appear as they get closer to commercial or institutional success. Many of these artists here are nearly mid-career studio artists with connections to street practice, a substantial track record, and have taken great risks to challenge their work and their own perceptions.

Quoting McCormick again, “If we are to take graffiti and street art seriously, as not simply a method but a mandate, let us acknowledge studio practice as part of this process – but, equally importantly, understand the compatible, essential roles that action, observation and introspection play in progressive social art.”

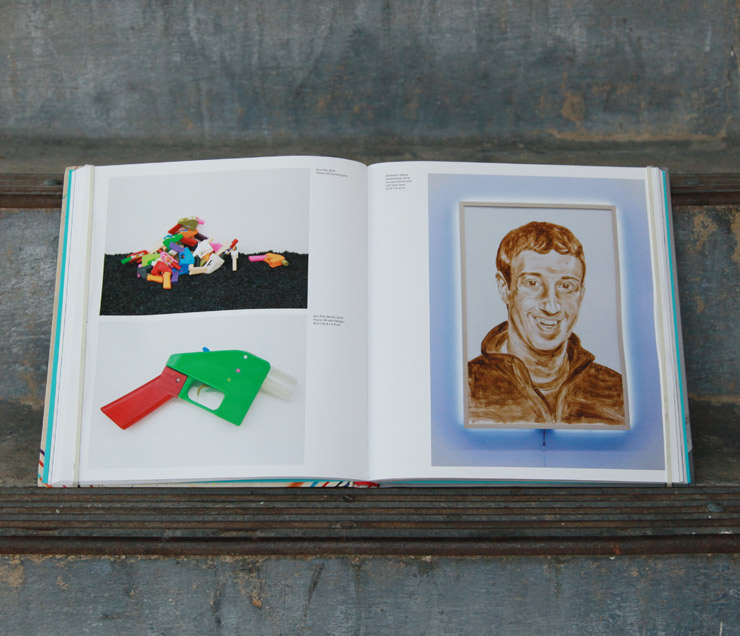

Rafael Schacter. Street To Studio. Katsu. Lund Humphries Publishers. London, 2018.

Excuse the tangent: In our own discussions here online and offline for the last decade we’ve noticed a certain “whitening” of the landscape as we get closer to certain environments like fine art or contemporary art. In the ongoing class war that is human life on Earth, the assured divine nature of the resource winners is ever buffeted by a self-created system of rewards and penalties and cleverly clouded demerits – and you can see this at art fairs and galleries some times. While many advents of style and practice may emanate from more grassroots origins, those originators have not always successfully claimed authorship of those great ideas once they have permutated into textbooks that tell the history.

Graffiti and Street Art have often been maligned, marginalized, and dismissed rather openly and subtly by many of the current class of museums, press, academics, collectors, and those aspiring to be them during much of its evolution, even if its techniques and conventions are imitated and appropriated. Now less tentatively embraced by adventurous collectors and institutions, there is still the trouble of how to present the work; currently afoot is a rebranding as Contemporary Art that imparts a crisp veneer of coolness without the association with less desirable traits.

You know which traits.

Rafael Schacter. Street To Studio. Barry McGee. Lund Humphries Publishers. London, 2018.

We have even been asked by some artists to stop calling them “graffiti writer” or “Street Artist” because they no longer want to be associated with the label, preferring “painter” or “contemporary artist” instead. Part of this is self-marketing, yes, and the aging of the terms that doesn’t quite encompass their current work. We can’t help thinking that part of it smacks of classism and classic eurocentric racism.

In the broadest manner of description, it’s generally accepted today that the hallowed halls of academia have held centuries of Eurocentric art evolution in the highest regard and dispensed with the contributions of most everyone else not willing or able to stroke the narrative of white straight male supremacy – this is understandable tribe-like behavior meant to insure a narrative about relative importance and in furtherance of these guy’s power.

Sorrily, it has often also been a disabling and narrow view that has lead many to miss and mis-characterize absolutely amazing contributions to culture and the canons, and we are all poorer as a result. The original graffiti artists cared little about these institutional views and looked instead for opportunities to be seen and heard by their peers and the public.

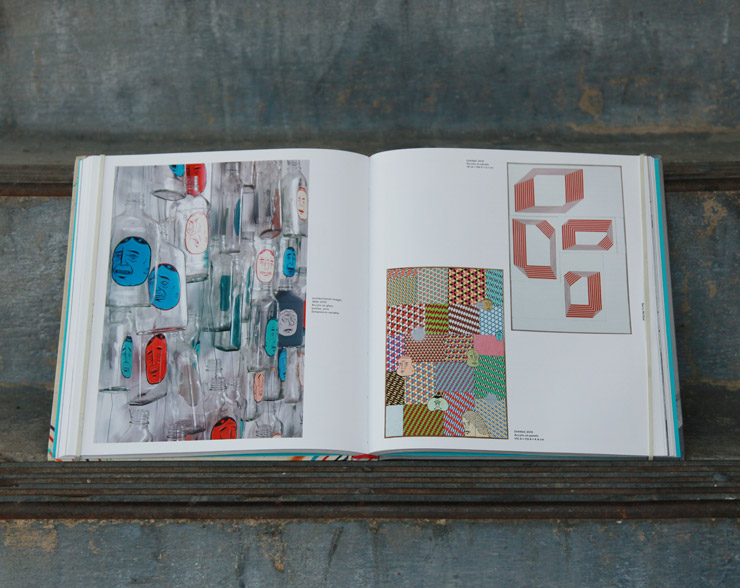

Rafael Schacter. Street To Studio. MOMO. Lund Humphries Publishers. London, 2018.

These observations are not directly related to the author or artists presented in Street to Studio but you may safely surmise that some of this work would be so far removed in traditional associations with train bombing and b-boys that many would say the relationship is thin, or tenuous – and it is sort of remarkable how refracted the field becomes.

It has been a continuous peregrination over five decades of course – this movement between the street and the fine art world and the commercial interests – with graffiti writers spraying across canvas in the seventies, collectors like Wicked Gary gathering tagged stickers on cardboard; art school kids like Dan Witz arranging garbage across the sidewalk in New York’s East Village in between classes at Cooper Union.

“The reciprocal flow between studio and street continues today, with ever more complexity and mutual sway,” writes art critic and cultural observer Carlo McCormick in his introduction to Street to Studio, and Rafael Schacter has undertaken with a scholarly eye this unthinkable task of measuring that complexity. The results are a thoughtful and considered collection of individual histories and practices, supported by his own research on the evolving academic discussions that will define the era.

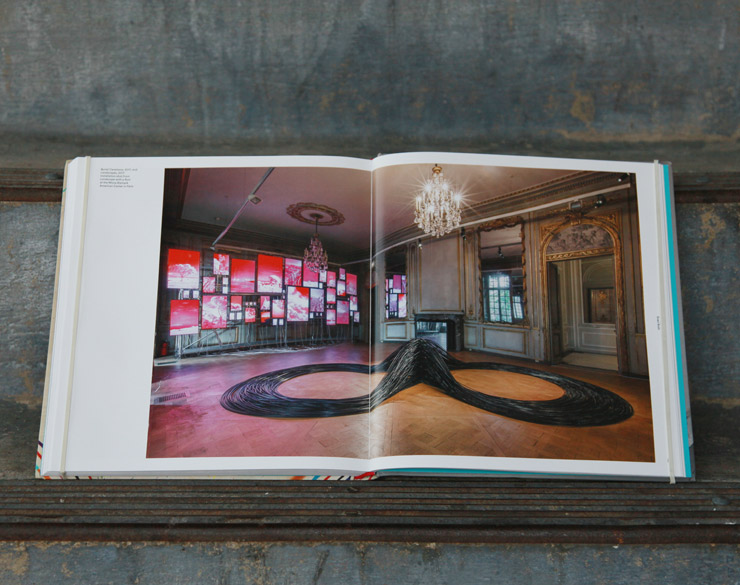

Rafael Schacter. Street To Studio. Evan Roth. Lund Humphries Publishers. London, 2018.

The graff-writing culture persisted; it evolved and nurtured and inspired a few generations and studio practices that followed. Street Artists work has spread across entire continents and into cities around the world without help from institutions, public programs, or academic approval. Now it merges with all our modern fashions in aesthetic and intellectual art-making yet it stands on its own – even as we grapple to document and describe it.

“The development of a distinct studio practice and institutional oeuvre is key to the text, even whilst this may disregard some important artists working today,” says Schacter regarding his methods of analysis for inclusion in this particular story.

“Overall, what was key was to provide a rounded selection of artists working in diverse formal and conceptual manners – artists pushing their practice with the realms of architecture and abstraction, performance and painting, digital art and new media, yet whose output provides a perfect exemplar of the dense possibilities that graffiti can provide.”

Today a generation of art students who grew up with the transgressive social politics of punk and hip-hop and wore wildstyle lettering and drips on their backpacks and clothing have their imaginations permanently sparked and have inherited an automatic expectation that their art could and should be staged on the street as well, illegally for extra points. Those practices expand and evolve and the current results are here. It appears to be a two-way street between outside and inside.

The spirit of graffiti is without doubt here. We just may not have realized how many forms it could take.

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY