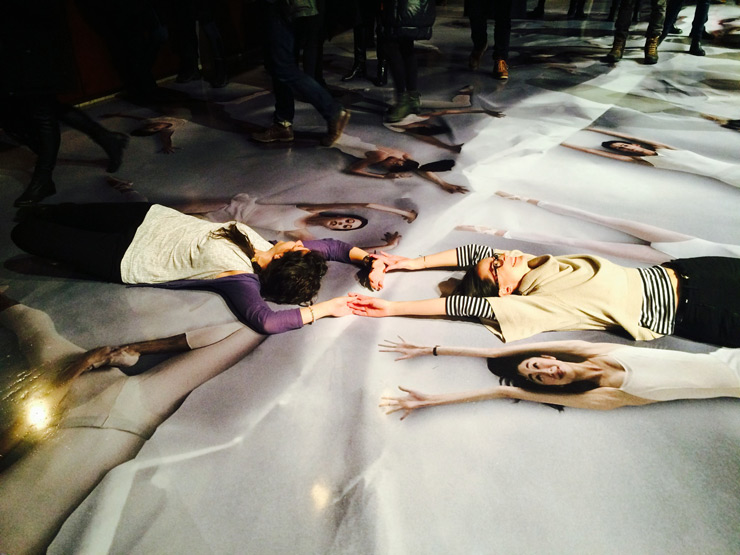

A big deal has been made about the so-called virtual experience of Street Art – made possible by ever more sophisticated phones and digital platforms and technology – producing a pulsating river of visually pleasing delicacies to view across every device at a rapid speed, and then forget.

Sit on the city bus or in a laundromat next to someone reviewing their Instagram/RSS/Facebook feed and you’ll witness a hurried and jerky scrolling with the index finger of images flying by with momentary pauses for absorbing, or perhaps “liking”. The greatest number of “likes” are always for the best eye candy, the most poppy, and the most commercially viable. It’s a sort of visual image consumption gluttony that can be as satisfying as a daily bag of orange colored cheese puffs.

This is probably not what art on the street is meant for. At least, not all of it.

Space Invader (photo © Jaime Rojo)

As we have been observing here and in front of audiences for a few years now, the 2000s and 2010s have brought a New Guard and a new style and approach to work in the street that we refer to as the work of storytellers. These artists are doing it slowly, with great purpose, and without the same goals that once characterized graffiti and street art.

London Kaye’s tribute to Space Invader. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

While there has been the dual development of a certain digital life during the last decade, these street works are eschewing the shallowness that our electronic behaviors are embracing. Even though the digitization of society has pushed boundaries of speed and eliminated geography almost entirely, it is creating an artificial intelligence of a different kind. In other words there really is still no substitute for being there to see this work, to being present in the moment while cars drive by and chattering pedestrians march up the sidewalk.

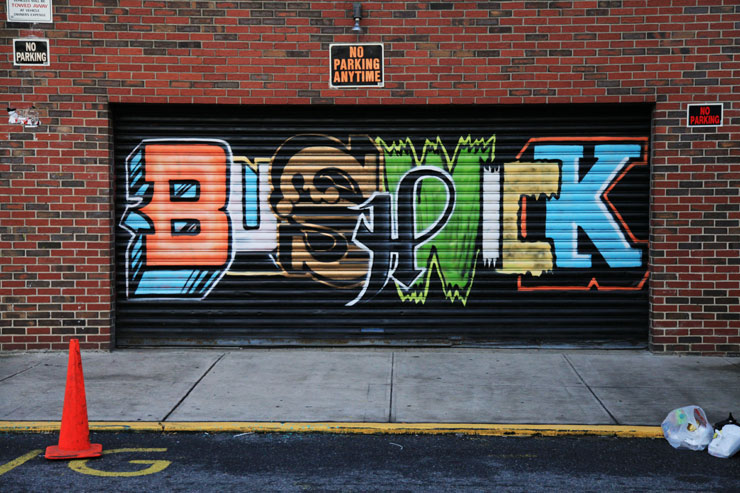

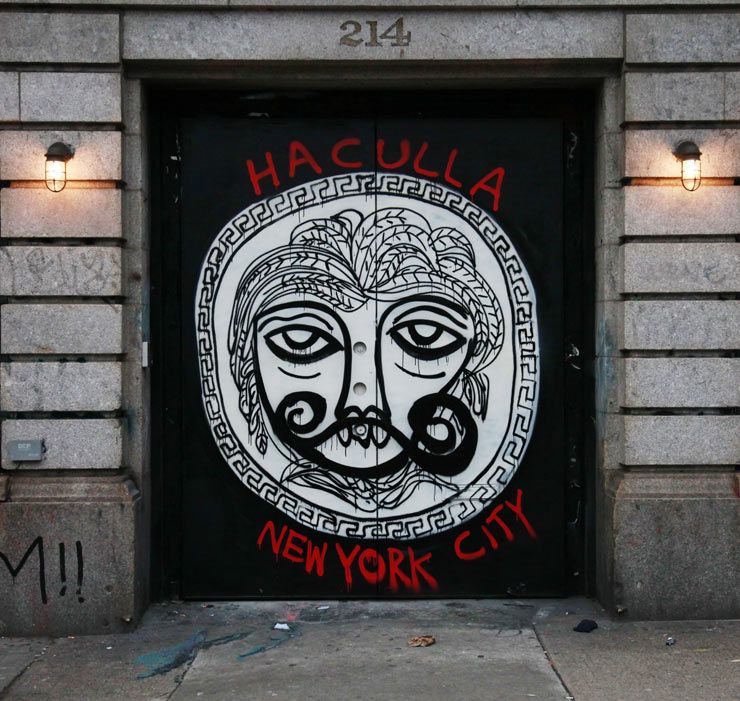

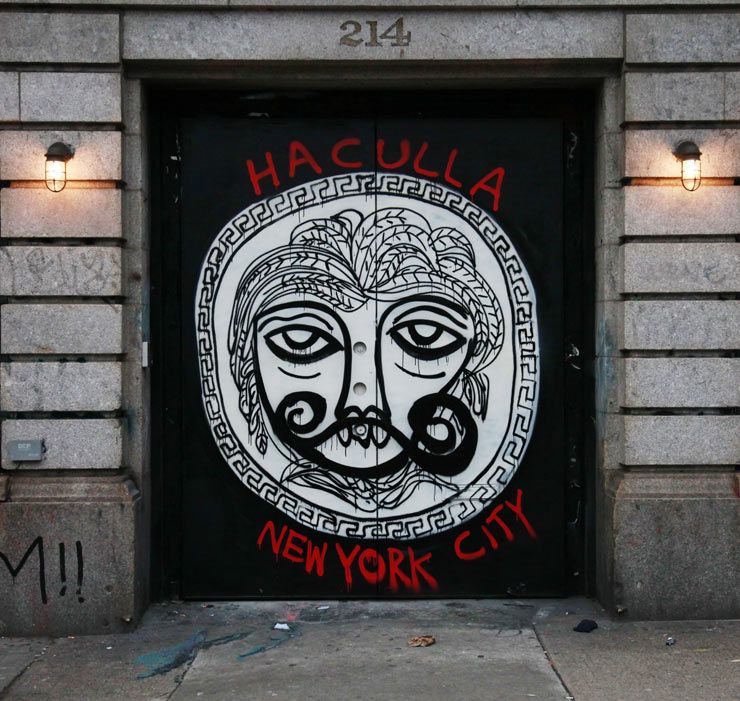

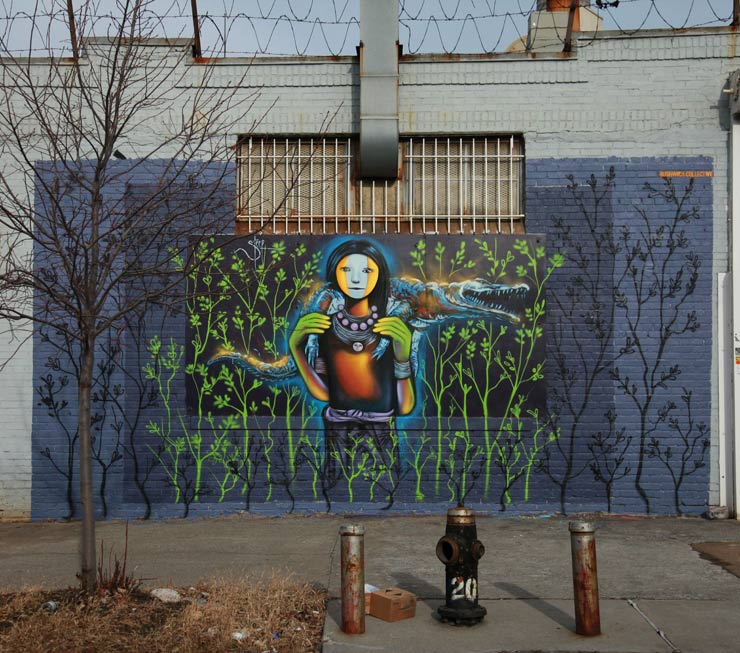

Setting aside the recent abundance of large commissioned/permissioned murals and the duplication/repetition practice of spreading identical images on wheatpasted posters and stickers that demark the 1990s and early 2000s in the Street Art continuum, today we wanted to briefly spotlight some of the one of a kind, hand crafted, hand painted, illegally placed art on the streets.

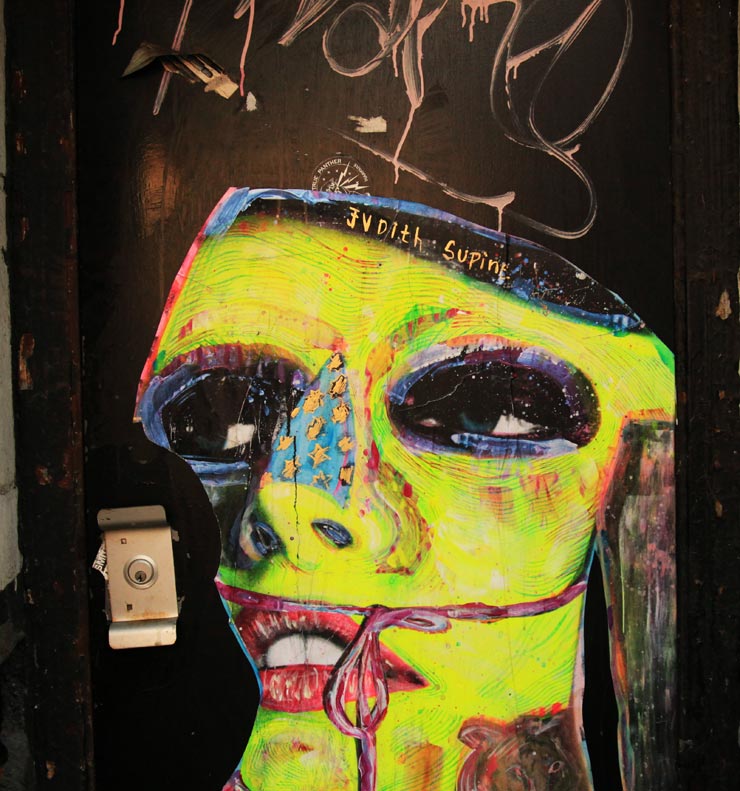

Judith Supine (photo © Jaime Rojo)

The materials, styles and placements are as varied as the artists themselves: Yarn characters attached to fences, tiles glued to walls, acrylic and oil hand painted wheat pastes on a myriad of surfaces, ink, lead and marker illustrations, carved linotype ink prints, clay sculptures, lego sculptures, intricate hand-cut paper, and hand rendered drawings have slowly appeared on bus shelters, walls, doorways, even tree branches.

They all have a few things in common: The artists didn’t ask for permission to place these labor-intensive pieces on the streets, they are usually one of a kind, and frequently they are linked to personal stories.

QRST (photo © Jaime Rojo)

We’ve been educating ourselves about these stories and will be sharing some of them with you at the Brooklyn Museum in April, so maybe that’s why we have been thinking about this so much. There is a quality to these works that reflect a sense of personal urgency and a revelation about their uniqueness at the same time.

If the placement of them is hurried the making of them it is not. The themes can be as varied as the materials but in many cases the artist informs the art by his or her autobiography or aspiration. And once again BSA is seeing a steady and genuine growth in storytelling and activism as two of the many themes that we see as we walk the streets of the city.

Jaye Moon (photo © Jaime Rojo)

Elbow Toe (photo © Jaime Rojo)

Mr. Toll (photo © Jaime Rojo)

Keely and Deeker collaboration. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

Square and bunny M collaboration. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

BD White (photo © Jaime Rojo)

El Sol 25 (photo © Jaime Rojo)

City Kitty (photo © Jaime Rojo)

Pyramid Oracle (photo © Jaime Rojo)

Bagman (photo © Jaime Rojo)

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY