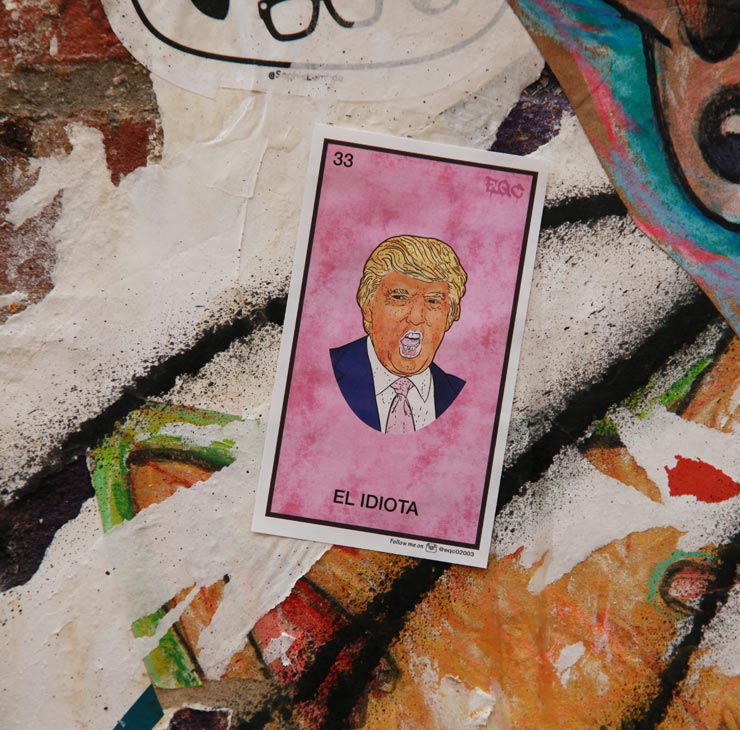

This is called disaster capitalism. It’s an actual thing – first gaining notoriety perhaps in Naomi Klein’s book “The Shock Doctrine”.

It involves taking advantage of a monstrous shock to our social and economic system while we are too preoccupied to stop them. People behind corporations actually “game” the future like this – methodically planning to force through changes to society that they always wanted but couldn’t find an acceptable justification for while you were looking. A crime committed right under your nose – while you are worrying about losing your job or paying your rent or your grandma getting sick from Covid-19.

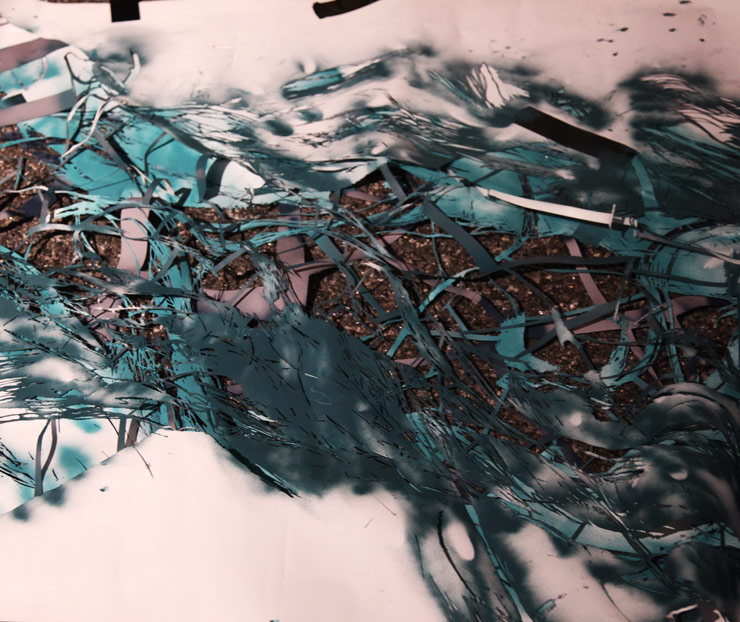

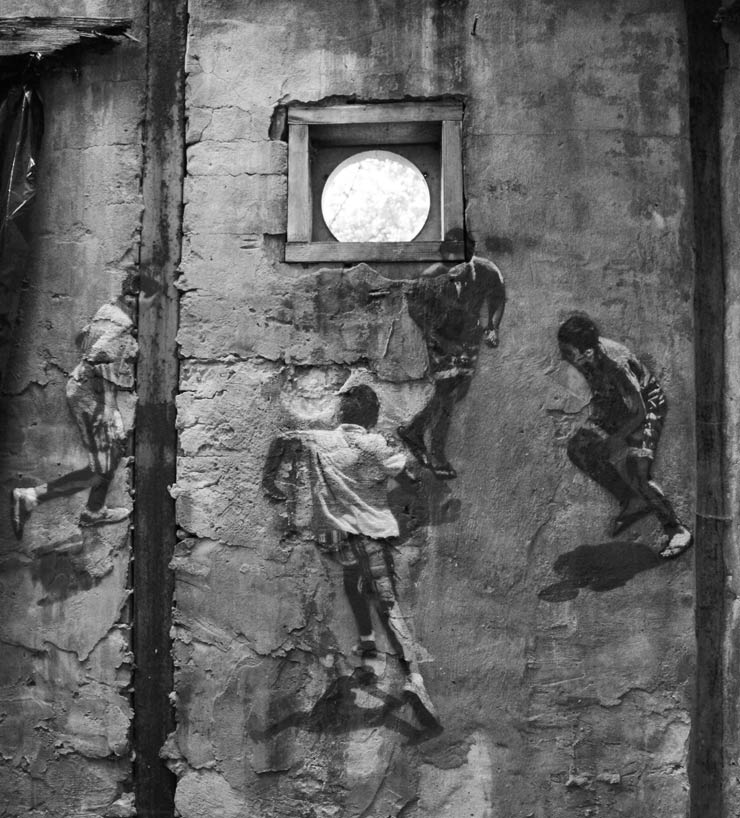

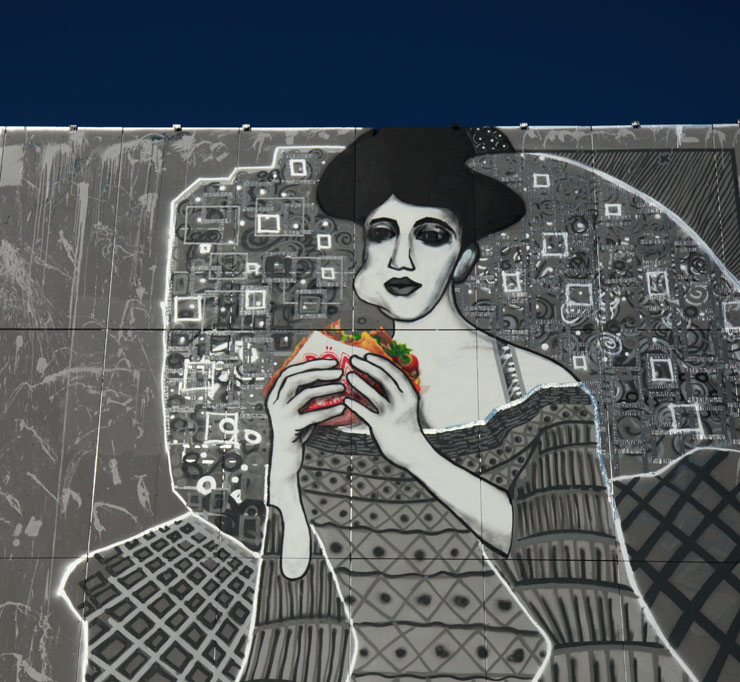

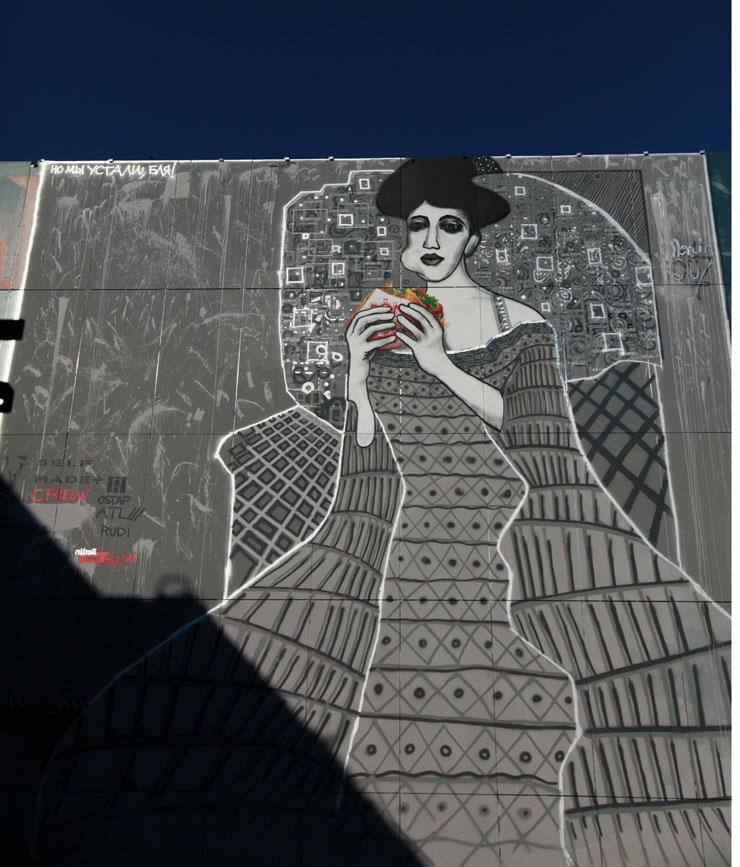

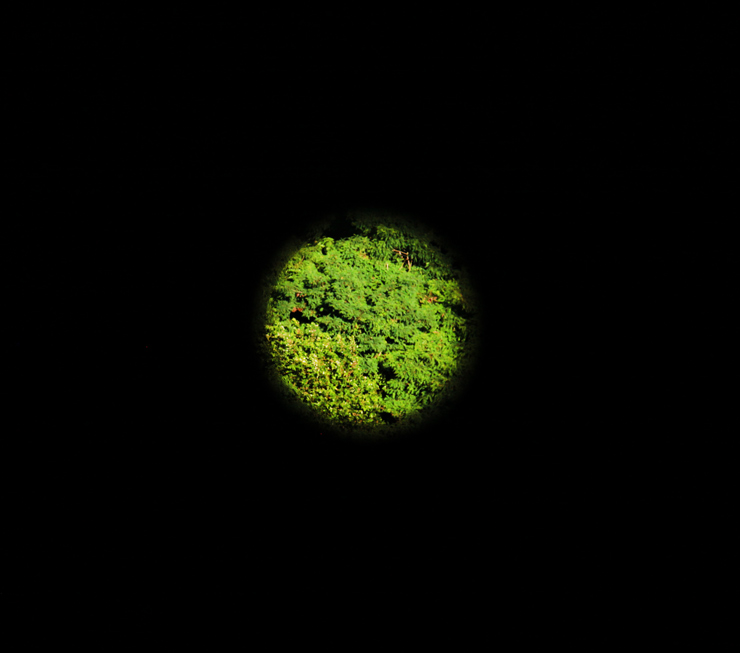

In the case of today’s story of a Brazillian Street Artist named Mundano, the earth, and soil that he used to paint his new mural comes from the region destroyed by a dam break of toxic sludge last January. With hundreds of townspeople and workers swept away by tens of millions of tons of toxic sludge and earth, the people of the area held searches for weeks after and had public meetings full of accusations and fury. They also had funerals.

A similar dam owned by the same company had failed only three years earlier, and many more dams like this are holding immense reservoirs, or poison underground lakes, across Brazil – each potentially breaking apart and poisoning land, water, wildlife, and communities for decades after.

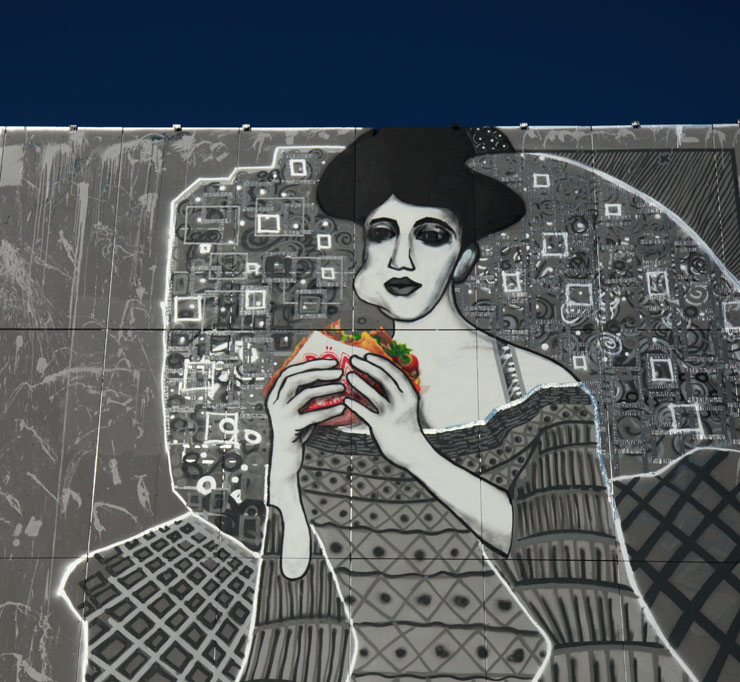

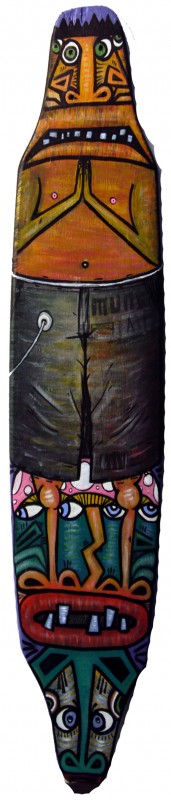

Mundano’s mural honors the workers killed in this man-made environmental disaster and he tells us that the 800 square meter piece references another painting Brazillian modernist called Tarsila do Amaral. Painted in 1933, her work titled “The Factory Workers,” depicts a sea of stern faces with gray clouds rising from factory smokestacks in the background. Mundano says he’s proud of his mural, of the mini-documentary here, and of his neighbors and country people who have raised attention to a situation that appears corrupt, and well, toxic to life.

“In January 2019, Brazil has suffered one of the worse environmental crimes of its history,” says Mundano, “when Vale do Rio Doce’s mining dam broke, contaminating the Paraopeba River with a sea of toxic mud, and killing everything that was in the way, including almost 300 people who lost their lives that day,” he tells us. We talk to him about artists using their work to educate and raise awareness to advocate for political or social change, a term often today called ‘artivism’.

Brooklyn Street Art: With reason, there’s a lot of anger against the government and the owners of the mine about this fatal catastrophe. How did you get involved?

Mundano: The environmental and social causes are a big part of my activism or artivism, and I’ve always been a critic of the exploitation of lands for mining purposes. We have over 200 mining dams operating today in Brazil under the risk of breaking. In the last four years we had two of the biggest catastrophes of our country, both in the state of Minas Gerais; Mariana in 2017 and most recently in 2019 in the city of Brumadinho, where a “tsunami” of toxic mud contaminated the Paraopeba river with 12.7 million cubic meters of sludge, dragging everything that was on the way, including almost 300 people who lost their lives.

As an artivist it is really important for me to be present and see what happened with my own eyes, feel the pain of the victim’s families, follow closely to the inquiry and use the platform and reach that I have as an artist to help these people find justice, and most importantly to put pressure on governments and big companies so that they’re held accountable, preventing this from happening again.

Brooklyn Street Art: What is the role of an artist should be in his/her community? Should art respond to social needs?

Mundano: For over 13 years now, I’ve been practicing artivism in several cities across the globe. My actions and the art I create need to have a bigger purpose. For me, art has the power of bringing reflection into society and impact people’s lives, make them think and reflect on their part in society. That’s how I see my art and how I believe I can contribute to bigger causes. I wouldn’t say it’s every artist obligation, but with these huge global challenges naturally we’re gonna need to become more artivists.

Brooklyn Street Art: The community felt betrayed and abandoned by those who were supposed to protect them. How did they get the strength to rise up and fight in the middle of their pain?

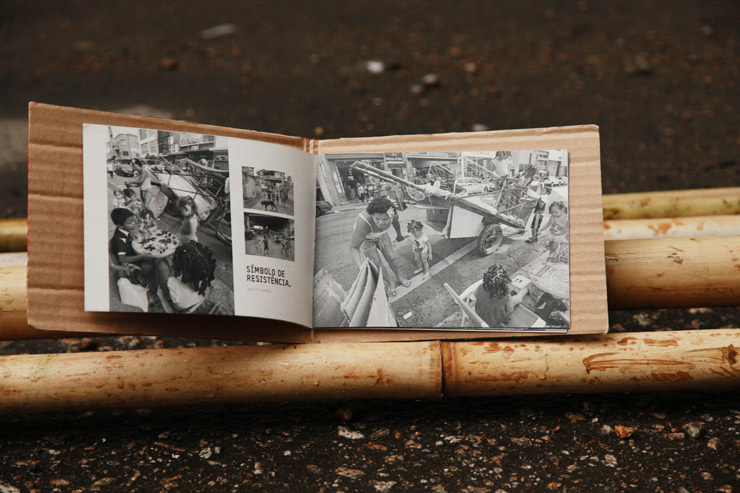

Mundano: I can’t speak for them but I feel that they don’t have other options than to fight for their rights. Brazilians are quite resistant to adversities by nature. One of the main subjects of my work is the cactus, a plant that, like a big portion of our population, survives with little and still manages to share beauty with flowers to the world. It is hard to see a whole city and it’s people destroyed by such a horrible crime, yet, it was such a strong image to watch mothers, wives, sons, daughters, and friends united, marching a year later, screaming for justice, not giving up on the memories of their loved ones. That gave me strength and inspired me to create my biggest and most important work up until today to honor them.

Brooklyn Street Art: Your mural honors and remember those whose lives were lost. Yet there’s some poetic beauty in it with the pigments you used to paint it. You made the paint from the sediment in the river and the earth around it. What were your feelings as you were painting these people faces these materials?

Mundano: The whole process of collecting the mud from the lakebed of Paraopeba River was delicate. I felt the need to talk to residents, local activists, and the families. It was important that I had their consent and that they understood my intentions. The mural was a way of keeping the subject alive, and to honor them in one of the biggest cities in the world, Sao Paulo. I believe that the respect I’ve shown was recognized as I started to receive messages from Brumadinho’s residents about the video, thanking me for the painting, and for me, that’s the biggest recognition of all, it made it all worth it.

Film by André D’elia

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY