C’est fini!

In 30 days Boijeot and Renauld slept with more of Manhattan than a Wall Street regulator. And the press was there to report it: The Huffington Post, The New York Times, Le Monde, the Today Show, Agence France Press (AFP), and a handful of art and design blogs all covered them from the street, intersecting with them at various points as they wended their way through Manhattan on their beds and chairs and tables for one entire month.

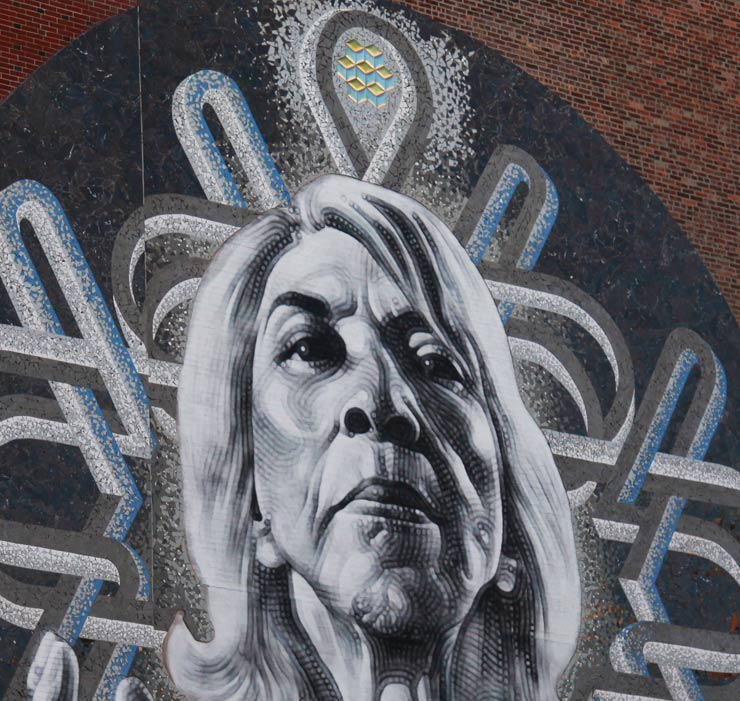

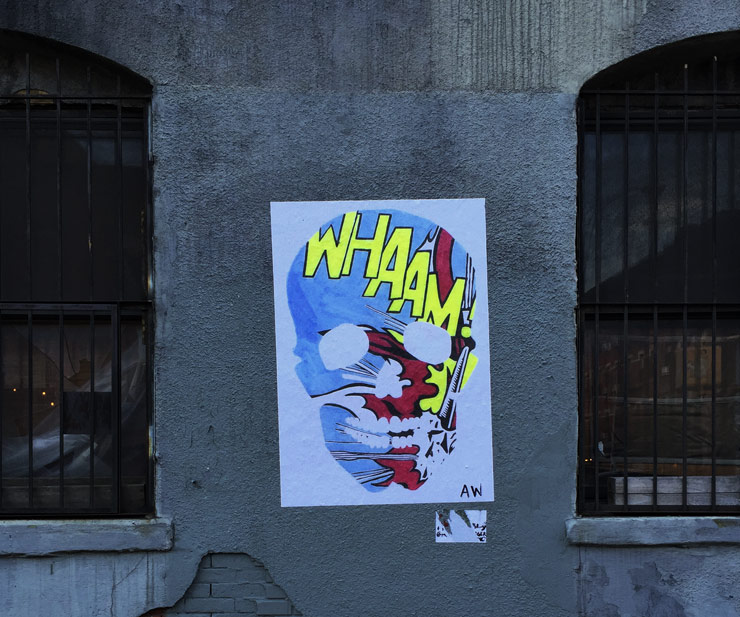

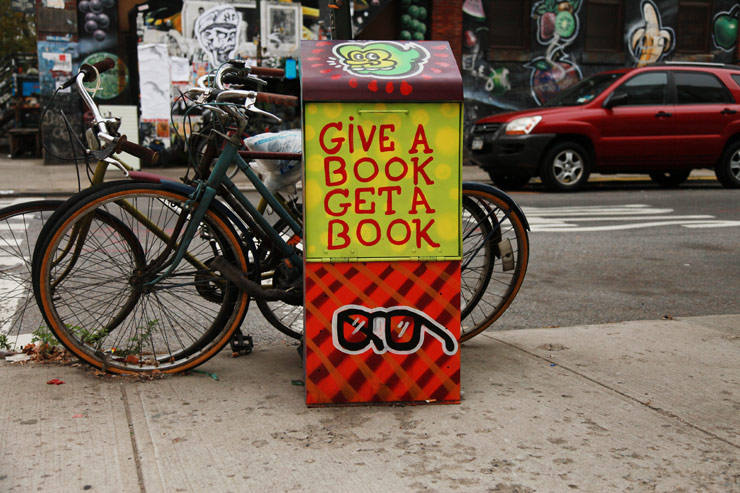

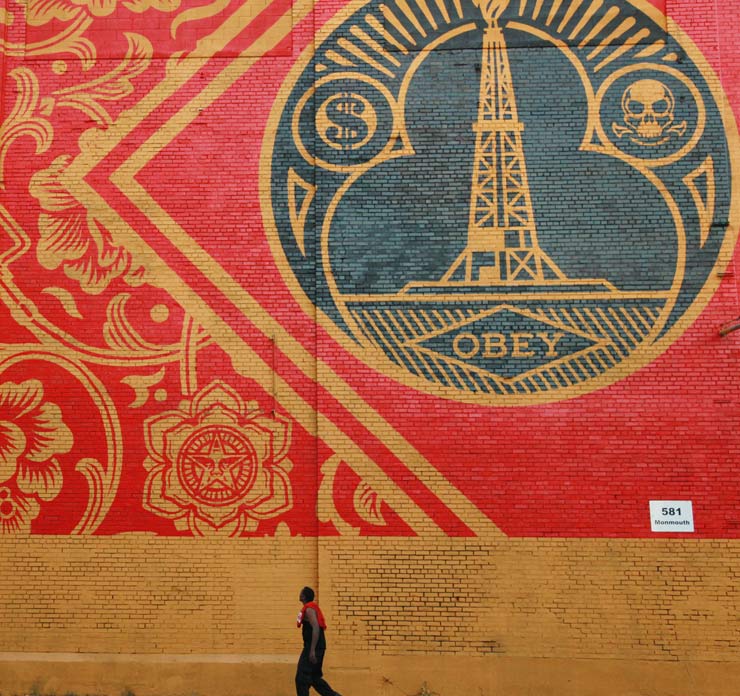

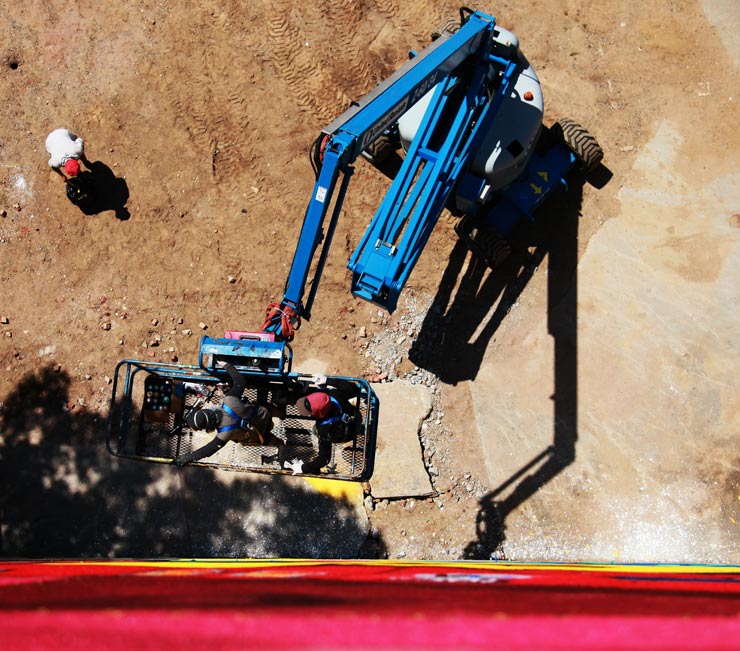

Boijeot & Renauld. Battery Park, Manhattan, NYC. October 24, 2015. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

A boisterous palm reader told Laurent that he couldn’t handle money and a sleek Tarot card reader told all three of them insights into their future. They were serenaded by an opera singer and a violinist, lectured by an art professor, visited regularly by an anchorman, argued with by an senior who wanted to leave his garbage on top of their table, doted on by smiling art school students and generous housewives, offered showers and house tours, proffered meals by chefs, accused of drinking alcohol and smoking pot (they did neither), and given a good show by junkies shooting up in Starbucks bathroom(s).

The two artists (Laurent Boijeot and Sebastian Renauld) and their trusty photographer (Clement Martin) each took turns fetching meals or water or fresh coffee or tobacco or to wash bed linens or get a hot shower at a gym or scoping out their next location a few blocks south. Taking exactly 30 days to live on Broadway from 125th street to Battery Park, Boijeot and Renauld say their days were usually busy, despite long stretches napping on beds and their central theme of sharing a cup of coffee with a stranger at the table.

Boijeot & Renauld. Battery Park, Manhattan, NYC. October 24, 2015. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

“The table was the most important part of the performance,” says Renauld as he describes the psychological grounding force of the simple pine rectangle around which the artists convened, and re-convened, and re-convened. People talked of their jobs, their families, their relationships, their aspirations and disappointments. The artists say that more than once they learned details of people’s lives that surprised them, pleasantly and otherwise.

Boijeot & Renauld. Battery Park, Manhattan, NYC. October 24, 2015. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

Police officers were friendly and even helpful once they understood the nature of the public art performance. In some neighborhoods some officers communicated back to their precincts details about the performance and they notified others who walked the beat that it was okay, with some even stopping by to say “hi” and take a photo. Most New Yorkers walked by nonplussed, uninterested, hurried. But invariably the questions would come; sometimes quizzically, timidly, other times demanding.

“What is this?”

“Are you protesting something?”

“Are you selling this furniture, how much is it?”

“Are you advertising for Sleep Ez?”

“Do you have a permit for this?”

“Can I sit here?”

That was their favorite question.

Boijeot & Renauld. Battery Park, Manhattan, NYC. October 24, 2015. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

Both artists insist that the “performance” on the sidewalk was to examine the interaction of New Yorkers directly with them in their al fresco kitchen.

“This is about the street being a place for sharing,” Boijeot says, “If we don’t use it for sharing our humanity then we really miss an important original meaning of the street.” He is the sociologist of the two, and if New Yorkers though that they were the observant ones, his descriptions of conversations and behaviors and mannerisms and attitudes quickly reveal that the artists may have subtly turned the table a number of times on Manhattan sophisticates.

Boijeot & Renauld. Battery Park, Manhattan, NYC. October 24, 2015. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

“So many people asked me if I had a permit – and I told them that it is legal to be in the street with your art and your furniture.” He laughs to remember the befuddlement. The artists learned that most didn’t fully comprehend their rights to free speech and association in public space. That was surprising.

In some conversations the issue of homelessness came up, with some New Yorkers asking them if their project was a commentary on homelessness, an idea they roundly reject. “It would be indecent to associate our project with homelessness,” says Renauld with some insistence, “because we are doing this easily and of our own freewill – but homelessness is not this.”

Boijeot & Renauld. Battery Park, Manhattan, NYC. October 24, 2015. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

The topic was raised a few times about their race and their French accents playing a big factor in the way mostly white Manhattan and its police regarded their performance. Surely if they were African American or of another background they would have received a different response?

The artists diplomatically demurred on the topic, saying that they did not feel familiar with the city enough to offer an opinion, but Renauld says they do not doubt that their skin color made the project easier for certain people to appreciate. “These are important questions to consider – along with homelessness, etcetera, but we don’t think it is our role to address them,” says Laurent, “That is the role of citizens and institutions.

Boijeot & Renauld. Battery Park, Manhattan, NYC. October 24, 2015. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

Lifting furniture and carrying each table, chair, stool, and mattress was tiring after a while and the feeling of performance was 24/7. Keeping clean was a challenge as was getting cell phones charged and figuratively they each slept with one eye open as pedestrians, cars and bicycles passed by all night, every night. Fierce rains pummeled them under plastic tarps and when those failed because of winds they spent a few hours looking out at the storm from inside an ATM lobby. Temporary handwarmer packs emanated just enough heat when the temperatures neared freezing, and sleeping fully clothed under a blanket was usually sufficient, especially if joined by a new friend.

The most surprising thing was when strangers would say “Thank you for coming here,” or “Welcome.” These were not the stereotype of New Yorkers they had learned from movies and stories.

Boijeot & Renauld. Battery Park, Manhattan, NYC. October 24, 2015. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

What did they see that was not something to write home about? Without a doubt, private building security guards took the cake; caustic mini generals with an exaggerated sense of power and an underwhelming sense of humanity, or the law. Like the two guys who woke them at 5 a.m. on 38th street to tell them to get out of the sidewalk because they didn’t want homeless sleeping there when office people were arriving to work – and they threatened to call the police. “I said, ‘Call them, I hope you call them right now because they will come and tell you that it is legal for people to be here,” They didn’t call.

Another guard menacingly pointed up to a window and said the tenants did not want to see the sight of them there. Then there was the doorman of a well-heeled building in the Wall Street area who woke them to tell them they were blocking the entrance. “The lobby was under renovation and people were going in and out of the side doors,” says Sebastian. “I looked at the orange construction tape draped across the front door and said to him ‘I know you are making a joke!’”

Boijeot & Renauld. Battery Park, Manhattan, NYC. October 24, 2015. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

So finally after more blocks than they could count, Boijeot and Renault and their camera man Clement made it to Battery Park on Saturday night. Two days before their friend Geraldine had arrived from France for her first time in the States. She has been on many of their other performances in European cities like Berlin, Brussels, Zurich, Venice, Paris, Basel, Dresden, and their hometown of Nancy, and she wasn’t going to miss this opportunity to be part of their first US performance.

As the sun was setting on the glistening harbor a quintessential “New York Moment” arrived; a sailing ship pulled up to shore alongside the park and Clement inquired with the shipmates if they might have a ride in the harbor. He must have been persuasive because within moments Clement and Geraldine were headed across the bay toward the Statue of Liberty –sitting atop the artists bed on the main deck.

Boijeot & Renauld. Battery Park, Manhattan, NYC. October 24, 2015. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

The view of Lower Manhattan was breathtaking for her, overwhelming for him. “I looked up at the skyline of Manhattan from a distance and it was like all of the pressure of the street was released, and I felt exhausted,” says Clement. So he laid down and napped for an hour of the two hour ship ride.

After a final dinner at an extended table with new and old friends they dined on Mexican beef, beans, and rice from a chain restaurant nearby, followed by store-bought red velvet cake and hot coffee. The midnight breeze blew quite chilly and a little sharply.

The artists pushed the three beds together, inviting everyone to join them under cover for the last overnight sleepout. Jokes, cigarette smoke, portions of songs and poetry were all foisted into the air while artists and guests looked at the open sky and that little green lady from France out in the bay. Only 6 hours to sleep before this performance was over.

And three weeks till Tokyo.

Boijeot & Renauld. Battery Park, Manhattan, NYC. October 24, 2015. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

Boijeot & Renauld. Battery Park, Manhattan, NYC. October 24, 2015. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

Boijeot & Renauld. Battery Park, Manhattan, NYC. October 24, 2015. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

Boijeot & Renauld. Battery Park, Manhattan, NYC. October 24, 2015. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

Boijeot & Renauld. Battery Park, Manhattan, NYC. October 24, 2015. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

Boijeot & Renauld. Battery Park, Manhattan, NYC. October 24, 2015. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

Boijeot & Renauld. Battery Park, Manhattan, NYC. October 24, 2015. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

Boijeot & Renauld. Battery Park, Manhattan, NYC. October 24, 2015. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

Boijeot & Renauld. Battery Park, Manhattan, NYC. October 24, 2015. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

Boijeot & Renauld. Battery Park, Manhattan, NYC. October 24, 2015. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

All furniture made by Boijeot and Renauld in Brooklyn with machinery and facilities provided by local businessman Joe Franquinha and his store Crest Hardware.

Sincere thanks goes to Joe Franquinha “The Mayor Of Williamsburg” and proprietor of his family owned business Crest Hardware for his enthusiastic support of this project. Joe has always been an ardent supporter of the arts and the artists who make it and he came through again this time. Thank you Joe.

<<>>><><<>BSA<<>>><<<>><><BSA<<>>><><<>BSA<<>>><<<>><><BSA

Please note: All content including images and text are © BrooklynStreetArt.com, unless otherwise noted. We like sharing BSA content for non-commercial purposes as long as you credit the photographer(s) and BSA, include a link to the original article URL and do not remove the photographer’s name from the .jpg file. Otherwise, please refrain from re-posting. Thanks!

<<>>><><<>BSA<<>>><<<>><><BSA<<>>><><<>BSA<<>>><<<>><>

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY