“Bodies Of Knowledge”

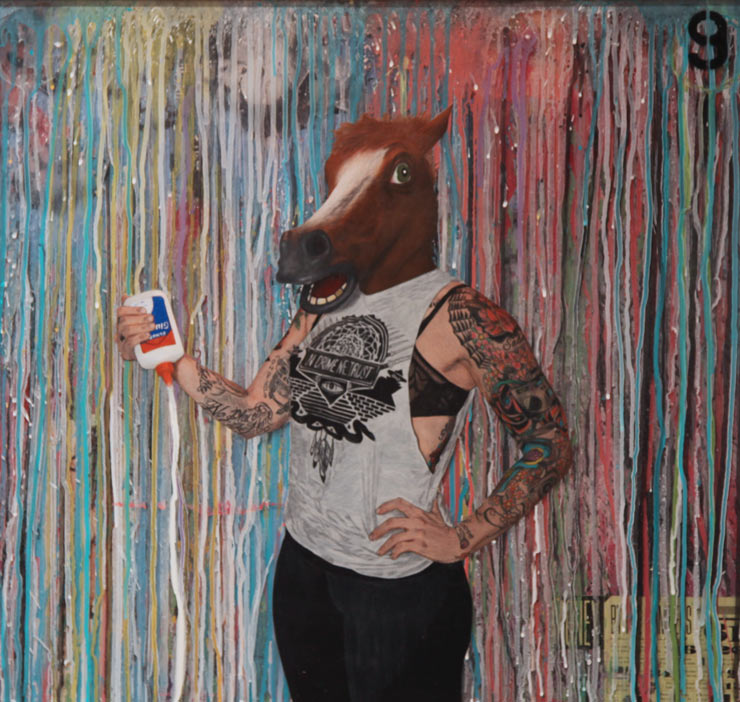

People have tried to make a case for blatant sexism in the percentage of women represented in street art. The argument of discrimination can only go so far, usually because the practice is largely anonymous and viewers are drawn to what they like, a selection process that has little to do with curation and mostly to do with showing up.

That was not the main concern of the Guerrilla Girls—they had already been accepted at and attended art school and expected the same opportunities as their male counterparts. The issue was gallery and museum representation, and the topic of privilege came into focus. They took it to the streets since arguing with well-financed art galleries and institutions requires thinking outside the box, if you will.

In general, the Guerrilla Girls didn’t come from the streets. They came from art schools and MFA programs, opening nights of student group shows, and long conversations about history and theory. Post-college and competing for the attention of gallery owners and museum curators, they became aware of the limitations of a privilege that appeared to extend primarily to males. According to their genesis story, a 1985 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art galvanized growing feelings of activism: its so-called “International Survey of Recent Painting and Sculpture” of 169 artists contained about a dozen women and few people of color. It wasn’t a mistake—it was a message.

The newly forming Guerrilla Girls read it loud and clear: you’re invited, but primarily as decoration.

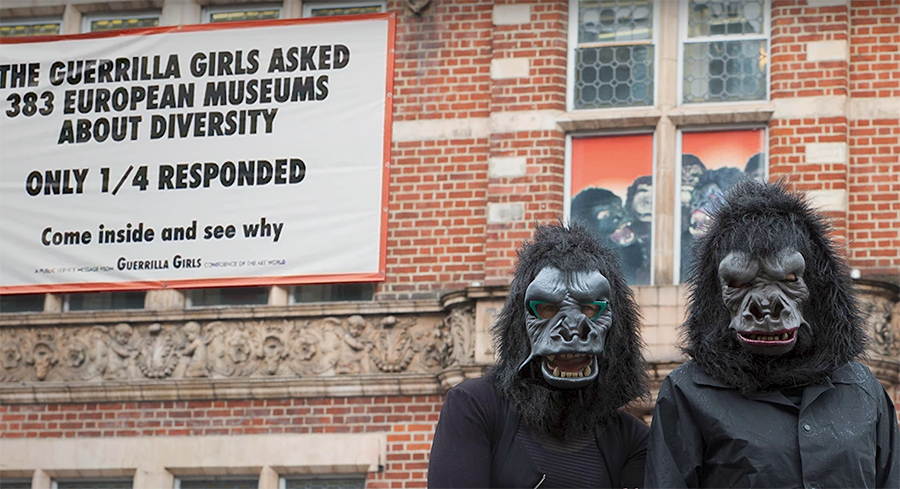

Gorilla masks on, dead women’s names adopted, and fists full of stats. If the art world wanted them silent, invisible, and grateful, the Guerrilla Girls made themselves unavoidable.

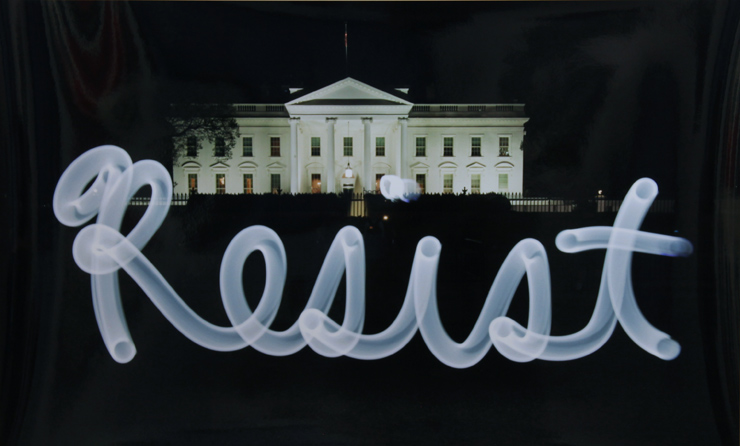

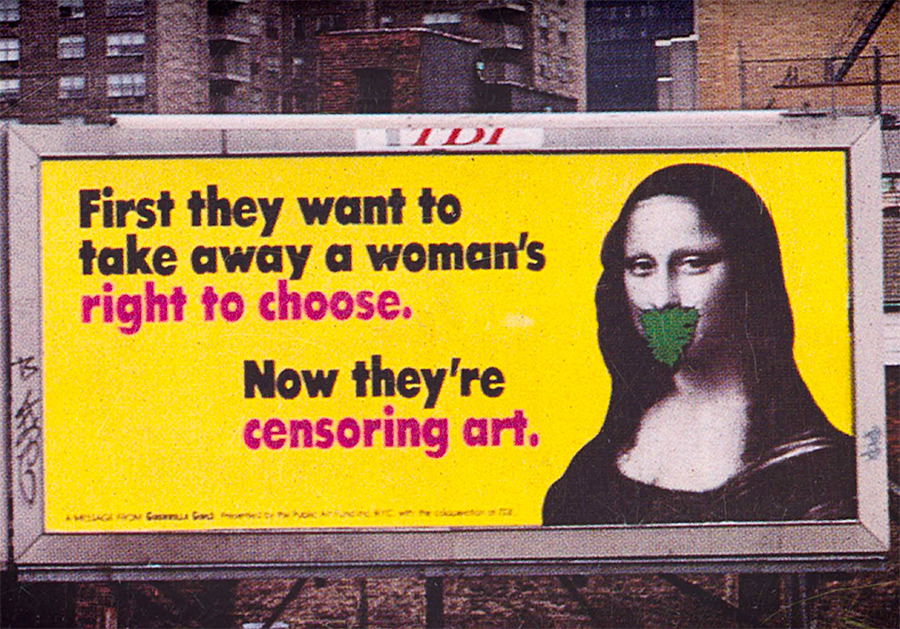

They took the fight to the street. Not with spray cans or stencils, but with wheat-pasted posters and billboard hijacks. They weren’t painting trains or tagging rooftops, but instead bases of light posts and SoHo walls and East Village gallery windows, blasting hard truths in bold type and asking questions the so-called art world didn’t want to hear: “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met?” The public space was their gallery, the street their showroom. Like the best street artists, they sidestepped permission and gatekeepers, relying on timing, location, and gut-punch wit to spark conversation and outrage.

Their background gave them access that others didn’t have. These were not outsiders trying to break in—they were insiders who got fed up and decided to cause dialogue and self-examination. It’s fair to ask why it took the exclusion of these particular women—many white, mostly well-educated—to spark such a visible rebellion. Black artists, Indigenous artists, and lower working-class artists had been sidelined for generations with far less ability to fight back. But the Guerrilla Girls, to their credit, did not pretend to have invented the problem. They made it their job to expose it. And they got people talking.

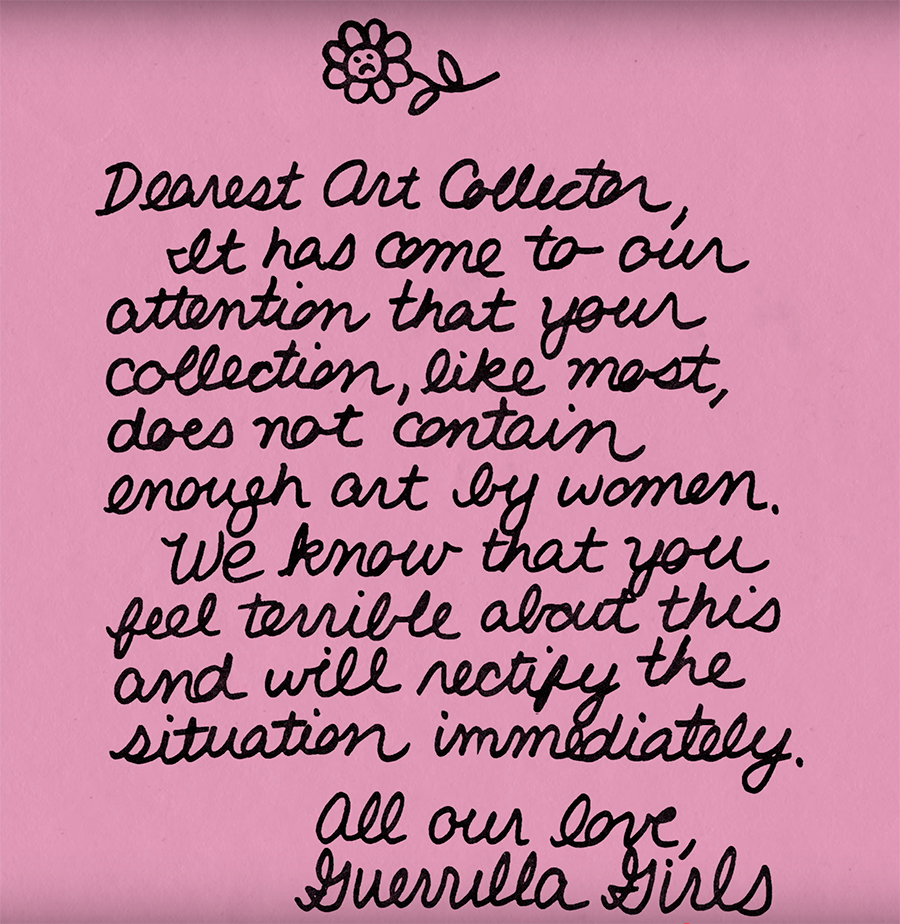

Their materials were simple: cheap black-and-white posters, loud fonts, unflinching numbers. It was lo-fi, hard-hitting, and anti-precious. In this way, their work mirrored the ethos of street art—accessible, immediate, and meant to be seen by everyday people, not just gallery-goers. While they didn’t use spray paint or wheat-paste murals in the traditional sense, their tactics aligned with the subversion lineage we see from billboard hijackers, adbusting collectives, and the Situationists’ “détournement.”

Like early graffiti crews, the Guerrilla Girls thrived on anonymity and collective identity. Their names were borrowed from forgotten or ignored women artists, their faces hidden by gorilla masks. The point wasn’t fame (well, not individual fame), it was force. By stripping away their identities, they pushed the message forward, not the messenger—a move that runs counter to the signature-heavy culture of graffiti writers, contemporary art, and celebrity-driven activism.

In the Art21 video featured here, one founding member recalls the moment things changed: “We were marching in a picket line in front of the Museum of Modern Art, and we realized not one person going into the museum cared.” That moment of invisibility led to a radical change in strategy—from polite protest to sharp, street-level provocation. Another member puts it even more plainly: “The more we looked at the numbers, we realized that there was a systematic elimination of women and artists of color from the so-called mainstream of the art world.”

Their critique wasn’t just about representation; it was about the money behind it, the power that shapes it, and the silence that protects it. From museum trustees to art collectors, from critics to curators, no one was safe from their data-driven, sarcastic broadsides. And as the video reminds us, they struck a nerve: “It wasn’t somebody else’s problem. It was my problem.”

Today, they are canonized in some museums that they once dragged through the mud. Their posters hang in frames. Their critiques have become part of the official curriculum. But their relevance hasn’t dimmed. If anything, the Guerrilla Girls remind us that the art world’s old power structures are more adaptive than we think. They know how to absorb critique and turn it into branding. And yet, the Guerrilla Girls remain difficult to digest completely—still masked, funny, and sharp. And still making trouble.

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY