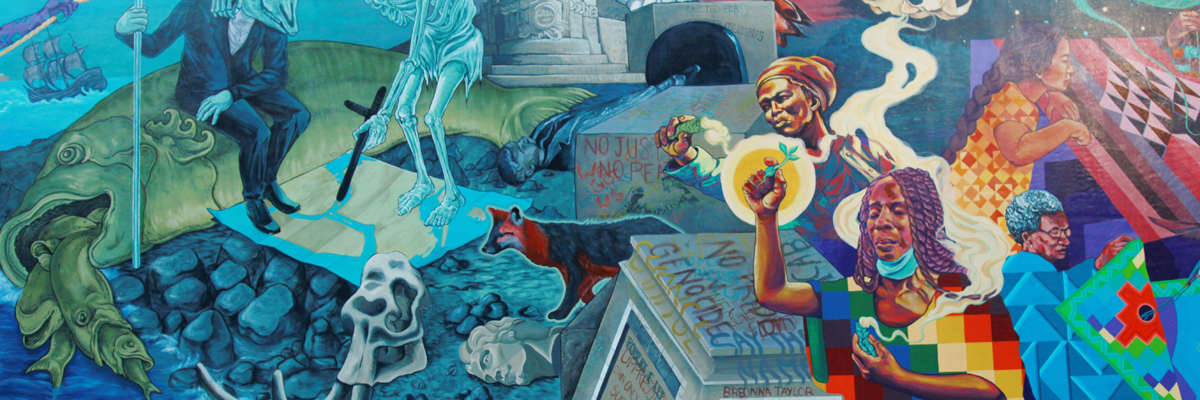

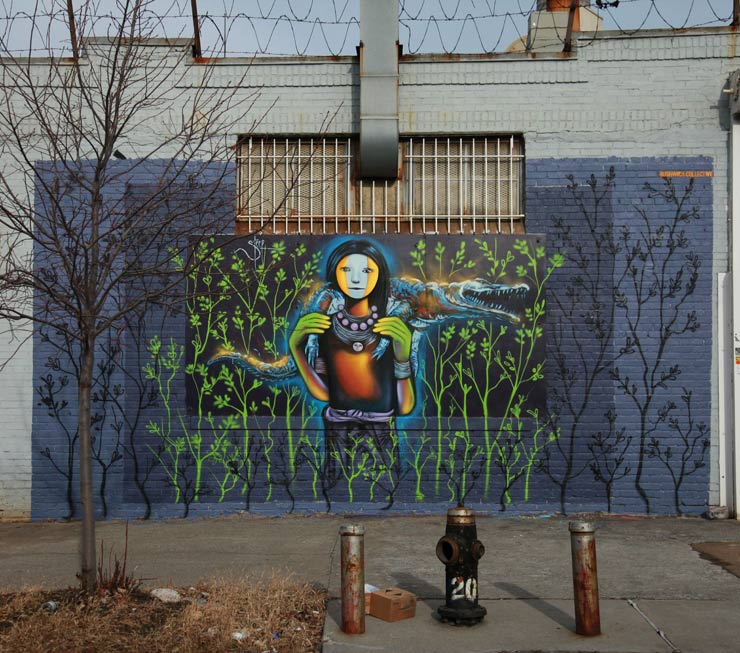

Steering away from potentially inflammatory political content or street beef of the past on this high-profile wall with a New York street art/graffiti history, the current occupants of the Houston Bowery Wall are more focused on allegory, and community. Featuring a fleet of volunteers and a mural full of history and aspiration, Raul Ayala thinks of this wall as a teachable moment. The artist employed many of the 21 days that this mural took to complete to do just that: teach.

With ten talented young artists/activists from the locally-based Groundswell NYC community organization, Ayala planned and painted various phases of the mural together while under the gaze of curious New Yorkers who paraded by hour after hour while the artists painted. Included in that team were Gabriela Balderas, Charlize Beltre, Brandon Bendter, Junior Steven Clavijo, Jennifer Contreras, Maria Belen Flores, Hafsa Habib, Cipta Hussain, Karina Linares and Gabriel Pala.

Ayala describes the piece as “opening a portal,” and you quickly realize that it is a portal of the mind to imagination and inspiration. “For me, building imagination and sharing knowledge alongside a younger generation of artists is a great manifestation of the fruits of this shift,” he says. “With this mural, we are also bringing inter-generational participation into a future that honors our past while actively creating a different path of existence.”

BSA talked to Raul about the mural and his experience painting it. Below is the interview:

BSA: At both ends of the mural you have depicted two masked characters. One on the left is wearing what seems to be an Aztec mask with the skyline of Manhattan in the background as he pulls down a monument. The one on the right is a black man at the moment when he is either about to put an African mask on or at the moment when he’s taking it off. Could you please describe the significance of both characters and how they relate to each other in the mural?

RA: Masks have always been a part of culture and are the recipients of many powerful archetypes; they are a space of connection to different realms of existence. In recent times, due to the pandemic, the mask has become necessary protective gear and is part of the current cultural landscape. With the masks depicted in the mural, I wanted to drive the conversation towards a more ample understanding of the mask as it relates to specific cultural heritages. Black, brown and indigenous solidarity is a constant effort in my practice. I strive to practice solidarity in the themes I paint and also in the way a lot of my murals are made. I think of mural-making as a learning space, where I get to have conversations with my peers and my students. African and Indigenous (Wirarika/Huichol) inspired masks have a lot in common, as one of the proposals for the idea of “opening portals” that is the overarching theme of the mural.

There is also a symbolic connection. In the Andes, where I come from, the Jaguar is a very powerful spirit animal related to water. The Black Panther as a representation of Black Power has a lot of cultural relevance as well and I wanted to hint to those connections. Many passersby have referenced one of the masked people as Chadwick Boseman. Even though it was not necessarily my intention, I love that people -especially younger generations- read that on the mural.

BSA: There’s a skeleton with his arm around a skull character in a suit holding what seems to be a scepter. What are these two doing in the mural and who are they?

RA: The whole mural is an allegory of our current times. For me, part of the work that needs to happen is to address systemic oppression and white supremacy as prevalent forces that are endangering our relationships to each other, to our ancestry, and to the natural world. The two characters represent these forces. There are also a lot of symbols relating to these structural powers: There is a big fish eating small fish and an Icarus falling, both as cautionary tales of a late capitalist society and its extractive, individualistic strategies.

BSA: Can you talk about the women that are making a quilt? Who are they? What do they represent? Why are they making a quilt?

RA: Textile arts at large, including practices like Quilting Bees have been spaces not only of resistance and resilience but also spaces to pass on knowledge between generations. I wanted to depict a pluricultural, multigenerational circle of women. I believe these are great examples of the kind of relationships that will sustain and create health in these times. Additionally, the designs are another type of “portal.” They are traditional symbols in different cultures; the women in the back are creating a “tree of life,” a traditional African American quilting design. The women at the fore are holding a Chakana, which is a very important symbol of the Andean cosmogony.

The central character is dressed in a Whipala, an emblem that represents indigenous peoples from the Andes. The animals that are coming out of the designs (with the exception of the hummingbird, which is a migratory bird) were part of the ecosystem of that very location before colonization. I took the information from the Welikia Project, a map that overlays the city with the ecosystem of Mahannata before 1609. I would also like to acknowledge that my partner Fernanda Espinosa, an oral historian and cultural organizer has been a great help in imagining this side of the piece, and with who I often collaborate.

BSA: The flowers on the mural are very similar to the Moon flowers one sees in NYC in full bloom at night during the summer. Are these Moon Flowers?

RA: It is great to hear all the different readings the public has. In the end, it is about what people take and interpret themselves, I love that the flowers can also be Moon Flowers. I wanted to bring the idea of passing on traditional knowledge through generations. The plant depicted is Guanto, a plant that has been used as medicine in the Americas for millennia.

BSA: The female character holding a seed or a seedling. Can you talk about her and the seed she is holding?

RA: This is another allegorical character that is both using plants as medicine and holding the seed as a symbol. For me, it talks about the idea of the future. The title of the piece is “To Open A Portal,” this seed may be seen as a sort of key to that portal; a key that requires sustained care so the fruits of the labor can be enjoyed in a possible future.

In Kichwa, one of the indigenous languages of the Andes, we can say that we are living through a Warmi (female) Pacha (time/space) Kuti (shift). These seeds also represent that Warmi Pachakuti. In a way, this speculative approach to the future that has a strong female character at the center is an homage to Octavia Butler’s oeuvre. The figure above is also a historical character, Harriet Tubman. These are proposals to enter a new monumental landscape, not necessarily to depict one main person, but the sets of relationships and changes they have created through their actions.

BSA: How was your experience painting in such a prominent spot with so much noise and traffic?

RA: I really enjoy working in public space! The conversations that I witnessed and that the mural and activity sparked were very interesting. A lot of people told me that they see themselves in the characters and that was one of the biggest compliments I have received. There were also some people triggered by what was perceived as an attack on “white culture.” For me to question white supremacy and celebrate protests in the midst of an unprecedented pandemic, allow us to place this shift in the context of History. When monuments are brought down, a sort of portal to a different reality is being created. I see this seemingly aggressive act also as an opportunity to manifest different futures: when a symbol that stands for the values of civilization is put into question, domination and power imbalances are being contested too. This portal allows us to walk through the pain and find futures where we consider the way in which we are not only connected but also dependent on each other.

BSA: Your assistants were also your students. Where do you teach?

RA: While I am a visual artist, teaching has always been an important part of my practice and one that I center often. I started first teaching art in a project I started in detention centers in Quito many years ago. Since then, I have taught with multiple projects and organizations. With Groundswell, I have had the pleasure to teach for about 7 years. This project was in collaboration with them and it really was the only way it made sense for me to do this wall. I have been witnessing the growth of these young artists for some time now and I feel very proud of them and what we have done together. My responsibility as an artist is also to educate the younger generations of artists of color.

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY