Graffitecture: Typographic Blueprints, on view at STRAAT Museum from February 14 to May 18, 2025, explores the evolving relationship between graffiti, typography, and the built environment. Curated by Hyland Mather, the exhibition brings together four artists—SODA, Gary Stranger, Antigoon, and Georgia Hill—who each push the boundaries of letterforms, blending street-born spontaneity with architectural precision. With around fifty works and several installations, the show underscores how graffiti’s evolution extends beyond its rebellious origins, shaping contemporary urban aesthetics through language and form.

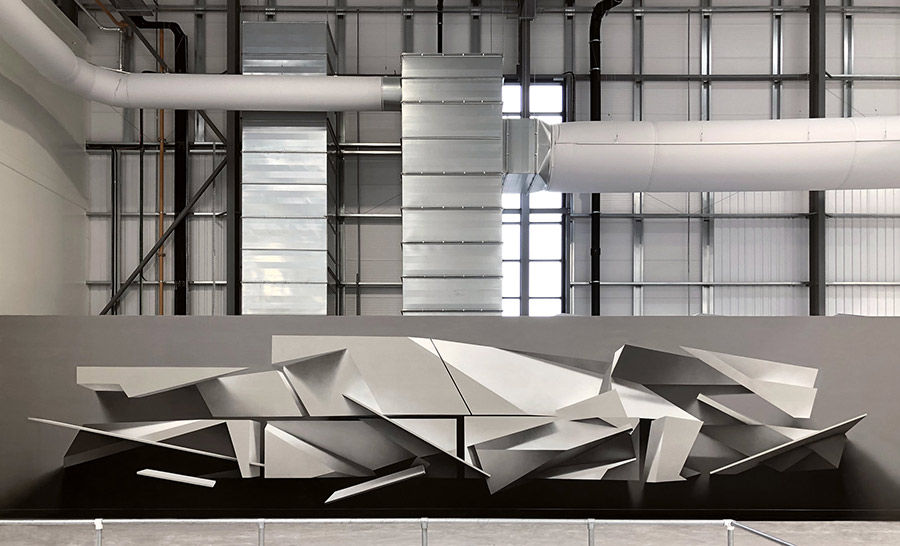

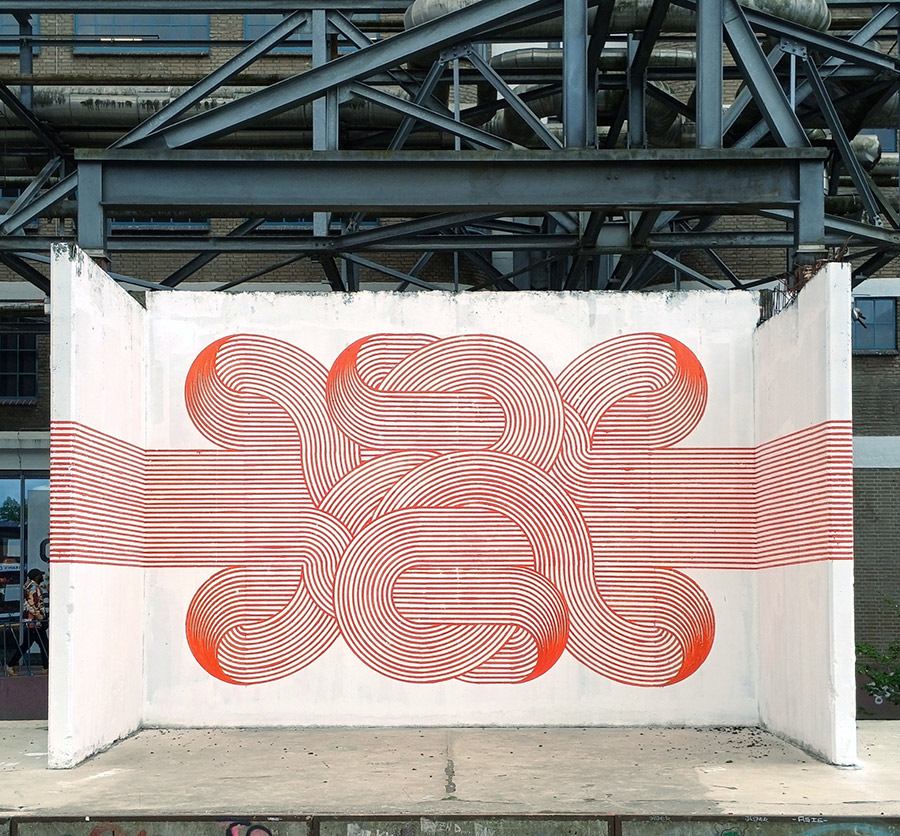

What unites these artists is their ability to challenge traditional notions of typography and its place in public space. SODA’s optical illusions introduce a trompe-l’œil effect, where depth and structure emerge from flat surfaces. Gary Stranger, with his graffiti roots in MSK, refines letterforms into architectural compositions that exude elegance and control. Antigoon’s machine-assisted process introduces an almost industrial approach, evoking the mechanics of urban construction. Meanwhile, Georgia Hill’s poetic monochromatic works harness language as both message and material, inviting reflection through carefully curated phrases. Together, they offer a dialogue between chaos and control, craftsmanship and spontaneity, underscoring how typography continues to redefine urban landscapes.

BSA spoke with Curator Hyland Mather and the four artists about their practice and the show.

BSA: As an artist known for assemblages of ‘lost objects’ and a curator deeply involved in street culture, how do you perceive the intersection of graffiti and architecture influencing contemporary urban aesthetics?

Hyland Mather: Well, to start, graffiti and architecture have always been in conversation…more than that, married. I mean graffiti happens on buildings. That part is as clear as it gets. But, graffiti isn’t just something on the built environment…it’s reacting to it, engaging with it, sometimes even fighting against it, protesting. And also, the rebellious or mischievous practice of graffiti is an ethos and attitude, and that’s a huge part of the allure and charm for the culture for both the viewer and the artists. So, not only does graffiti take place ON the architecture but also IN the cityscape, IN the architecture of the city in ways other artistic movements simply don’t.

In terms of contemporary urban aesthetics…which, we all know, is a moving target…I see the intersection of graffiti and architecture continuing to evolve in ways that go beyond just paint on structures. A lot of artists are playing with depth and layering, in ways that feel ‘in conversation’ with architecture. You’ve got geometric abstraction, precision lettering that mimics architectural lines, and even a kind of ‘graffiti expressionism’ (think NUG, or Revok, or even 108) where the movement and energy of tagging culture gets translated into something that engages with architecture more fluidly, without being so tied to strict letterforms.

More from our interview with the curator after the artists.

SODA

Brooklyn Street Art: Your work plays with three-dimensional illusions on flat surfaces, blending hyper-realistic and abstract forms. How do you approach the balance between abstraction and realism, and what challenges arise when scaling these concepts to larger works?”

SODA: That’s a great question. I tend to think abstractly when creating both my artworks and music. One of my main goals is to achieve a certain look and feel—something that appears hyperrealistic in detail, despite the limitations of the medium on canvas, certainly not on wall.

I aim to depict something that appears tangible, but within an abstract space—unreal, yet rendered with a sense of realism. However, when working with oil paints, I completely avoid hyperrealism. Instead, I focus on abstraction, using expressive brushstrokes and fluid compositions to create depth and movement. Light and shadow play a crucial role in shaping the geometry, while the mind instinctively fills in the details to form the bigger picture.

To me, abstraction and hyperrealism hold broad meanings. Their significance depends on how we perceive and approach them.

When creating, I use my own sound design as either a starting point for inspiration or as a parallel process. My approach remains abstract, even in music—where notes and rhythms follow a non-conventional, almost random structure. This randomness often leads to unexpected results, which can be more compelling than the initial idea. The same applies to my visual work, whether on canvas or walls—there’s always an intended direction, but the “unintended” elements often become a focal point.

On a larger scale, my work offers different spatial and design possibilities. Every piece presents its own set of challenges, from the initial sketch to the final execution. But to me, that challenge is an essential part of the process—an evolving interplay between control and spontaneity.

GARY STRANGER:

Brooklyn Street Art: Having started in graffiti in the 1990s, you’ve developed a distinctive freehand typographic style. How has that background influenced your work, and what drives your commitment to precision?

Gary Stranger: The graffiti I painted was heavily influenced by type. The characteristics and some of those letter forms have persisted through to the work I make today. The structure, rigidity, and legibility of my graffiti were important to me. I think a foundational understanding of letter form is vital if you’re going to paint good graffiti. I hope that understanding now informs my studio work in the same way.

I’m not sure I have a commitment to precision. I like order and I reflect that in my work. I am however trying to embrace the element of jeopardy in my current work. The nuances of the brush stroke and the imperfections of how the paint is picked up by the canvas are part of the joy now. Previously, I would have worked hard to eliminate these details.

I spent 25 years learning how to make spray paint do what I wanted it to, only to realise it was never the correct medium for the art I wanted to make.

GEORGIA HILL

Brooklyn Street Art: Specializing in type-based, monochromatic artworks, your pieces may reflect personal and poetic themes. How do you select the phrases you incorporate, and in what ways do you aim for your work to engage viewers on both individual and communal levels?

Georgia Hill: The phrases I feature in my works are collected over time, in a number of ways. Sometimes, I play with collaging words together, noting down misheard lyrics, or simply noting thoughts or phrases that play on my mind. I keep a long list of these and am always waiting for the right place to put them – whether that’s as a painting title, featured in an artwork, or ‘fit’ the facade I’m working with.

I hold onto these phrases because they reflect or stir something in me, but often have an ambiguous nature. I really like that they’re open-ended and a record of a fleeting moment for myself, but that people use their own experiences and contexts to build their own connections to the work, whether that’s on an individual level or reflects a sense of connection and community.

ANTIGOON

Brooklyn Street Art: Your work pushes the boundaries of material and process using custom-designed tools. What inspired you to incorporate these unconventional tools, and how do they influence the final aesthetic of your typographic forms?

ANTIGOON: I guess it all comes down to the computer-controlled machines I started building out of boredom after years of being a web designer. These were little pen plotters that drew my designs with pen and paper. They’re very neat and precise, which was really nice in the beginning because, apparently, I did a great job building them.

After playing around with this pen plotter for a while, the neatness became quite boring. I started to enjoy the little mistakes it made, like the little blobs of ink here and there, the less-pronounced lines, and the visible vibrations of the motors.

One time, out of curiosity, I started using charcoal instead of the usual pen on paper. For the first time, it became more of a collaboration between me and the machine. I had to change my design because the lines were a lot thicker than before, tape some metal brackets to the Z-axis to add the needed pressure, and babysit the plotter because the charcoal kept running out.

In hindsight, this sparked a new playground: Let’s feed this machine weird things. This collaboration is at times a battle – this is what really triggers me. The boundaries that come with using a certain material and a machine that’s actually not made for this are fascinating.

In the end, it’s all about the question: How can we make this work? Sometimes, I have to alter my drawings; other times, I have to add extensions to the machine, change the material a bit, or completely build a new machine. These challenges are what keep it interesting for me and, hopefully, for the audience as well.

BSA’s interview with curator Hyland Mather continues here:

BSA: In curating Graffitecture: Typographic Blueprints, what criteria guided your selection of artists, and how do their diverse practices contribute to the exhibition’s exploration of typographic transformation in public spaces?

HM: I obviously couldn’t include everyone—that’s always the first limitation, haha. But these four artists I think represent a good glimpse into something much broader that’s been happening globally. With these four artists I can help introduce this story to the visitors of STRAAT.

I wanted artists who manipulate letterform in unexpected ways, basically. Two of them, Gary Stranger (MSK) and SODA, came straight out of graffiti-writing traditions, while someone like Georgia Hill works more conceptually with language…like Barbara Kruger or Jenny Holzer but on the street.

Anyways, it just seemed to me that all four of these artists share a deep understanding of how typography and letterform interact with space.

BSA: Given your experience with found-object art, how do you see the concept of ‘reuse’ manifesting in the practices of the artists featured in this exhibition, particularly in their approach to typography and spatial design?

HM: Thank you for asking this. With these four, ‘reuse’ isn’t happening in quite the same way that I engage with lost physical objects in my own work. But there’s definitely a shared sensibility. I see parallels in how they repurpose visual language, reclaim surfaces, and reinterpret structures.

Graffiti has always been partly about taking what’s available and transforming it…buildings, bridges, train cars, power boxes…, and on and on. These artists are working from that tradition but doing what good artists should do and pushing the traditions. We see great examples from each of these artists in terms of rethinking letterform, reusing language, and reshaping typography.

There’s also a shared discipline in terms of approach. Like in my own work, I see a commitment to geometric abstraction, to working within a precise and often limited palette, and to an almost meditative focus on form. So while the materials are different, the mindset of taking what exists and flipping it into something fresh, I guess I would be speaking for them, but I definitely think we all share that.

BSA: How do you see the dialogue between traditional graffiti practices and contemporary design evolving, and what role do exhibitions like Graffitecture play in this progression?

HM: See, this is a good but tricky question…I mean how many young turks started off as graffiti writers and now work in cushy design industry jobs?…a nearly uncountable number, I think. Of course lines continue to blur … advertising for example, annexes more and more from graffiti and street art culture all the time. But, let’s not forget, traditional in your face name writing graffiti is still super strong and needed…repetition, name recognition, getting up, the whole ruckus…to me this part of the culture is in ‘non-dialogue’ with contemporary design. It can have an influence on the visual language of design, but the ruckus part of the culture will never truly be embraced by contemporary design, and thank fucking god, actually.

But anyway, to go back to how I started to answer this question … a lot of artists are applying design sensibilities and innovations to their street work. So instead of ‘Design always borrowing from Graffiti’, I like to think of it as ‘Graffiti sometimes stealing from Design’

The artists in Graffitecture, I see these artists as thinking about typography and letterform not just as a personal tag but as a system of communication, like a designer or an architect thinks of their work. Something that can be constructed or deconstructed, built or rebuilt. Of course this is not new, artists like DELTA have been exploring themes like this for a very long time, there are just now more examples of artists working like this in our global culture. An Exhibition like Graffitecture helps amplify the ongoing conversations between graffiti, design and architecture for our STRAAT visitors. We are so very proud to provide the venue and forum for such a cool and nuanced topic.

For more information about this exhibition click STRAAT

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY