Verona, Italy—known for Romeo and Juliet—is now also home to a very different kind of love story: one between food, public space, and antifascist resistance. At the center is CIBO, a street artist whose name literally means “food,” and who has made a career of turning hate speech into visual comfort food. His murals cover neo-fascist graffiti with pizza slices, cheesecakes, and bundles of asparagus, using humor and everyday symbols to defuse toxic ideology.

CIBO’s approach is clever—and disarmingly effective. Since he began his “recipe of resistance” over a decade ago, he’s been turning Verona’s walls into a living, evolving archive of antifascist art. Where others argue or censor, he paints tortellini. When fascist slogans reappear, he adds another layer—often building his murals like dishes, one ingredient at a time. It’s personal too, he will tell you: after neo-Nazis murdered a friend, CIBO says he doubled down, embracing public art as a peaceful yet persistent form of defiance.

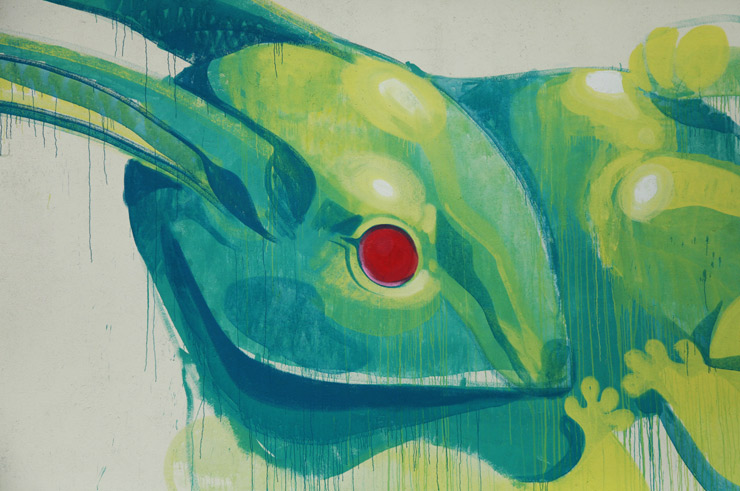

CIBO X MANTRA

This March, that individual mission became collective action. In an unsanctioned street art festival titled “Best Before. Street Art Against a Rancid Future,” CIBO invited 11 fellow artists—Claudiano.jpeg, Clet, Eron, Mantra, Millo, Ozmo, Pablos, Pao, Pixel Pancho, Plank, and Zed1—to collaborate on murals that replaced hate with imagination. The name? A cheeky reference to food expiration dates—reminding us that our tolerance for racism, nationalism, and repression should’ve expired long ago.

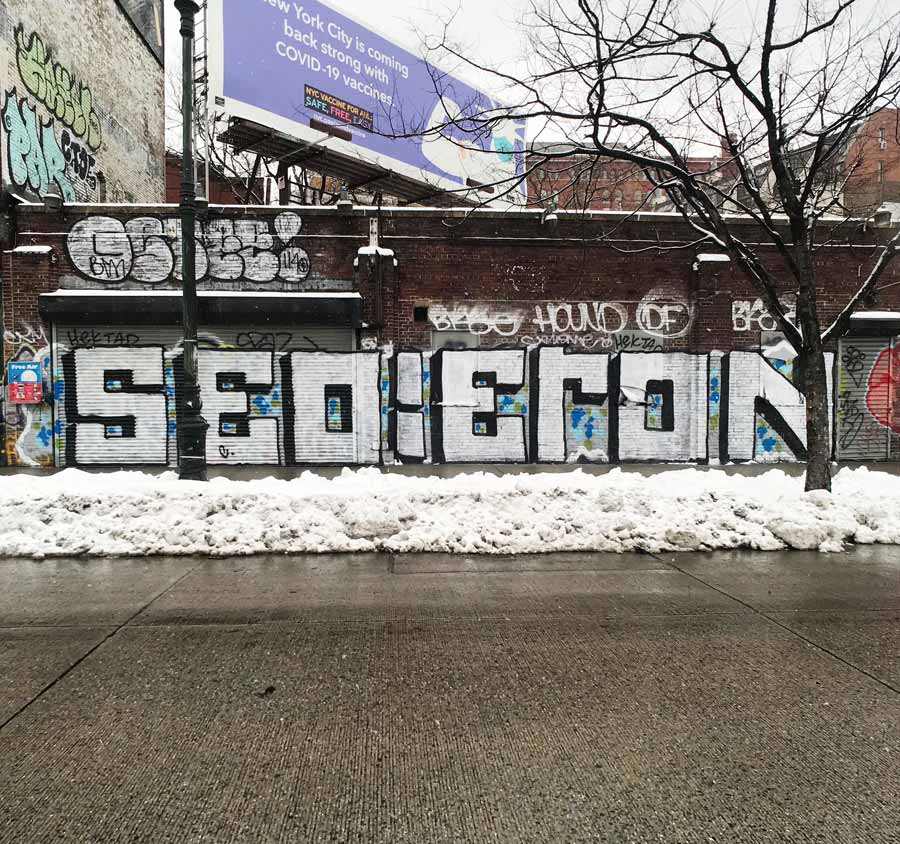

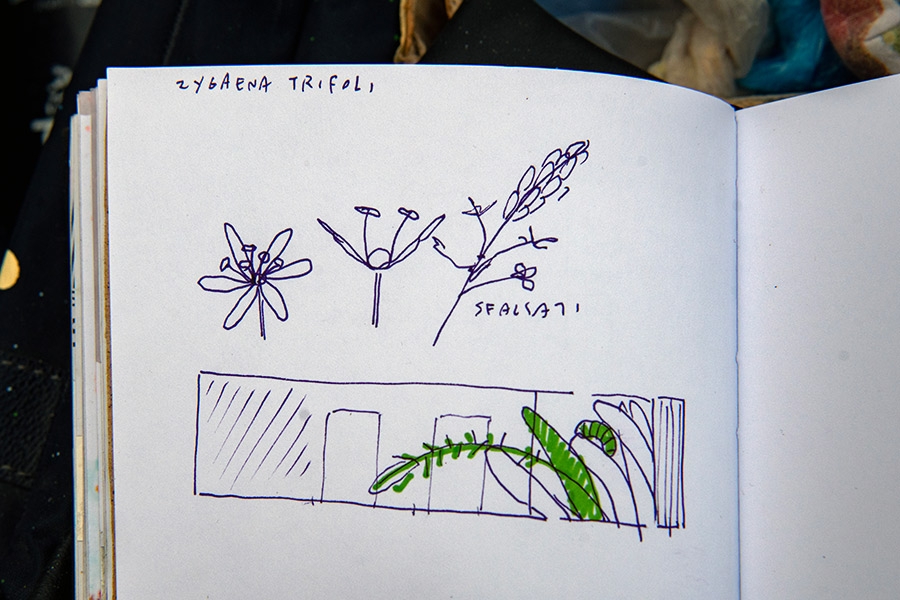

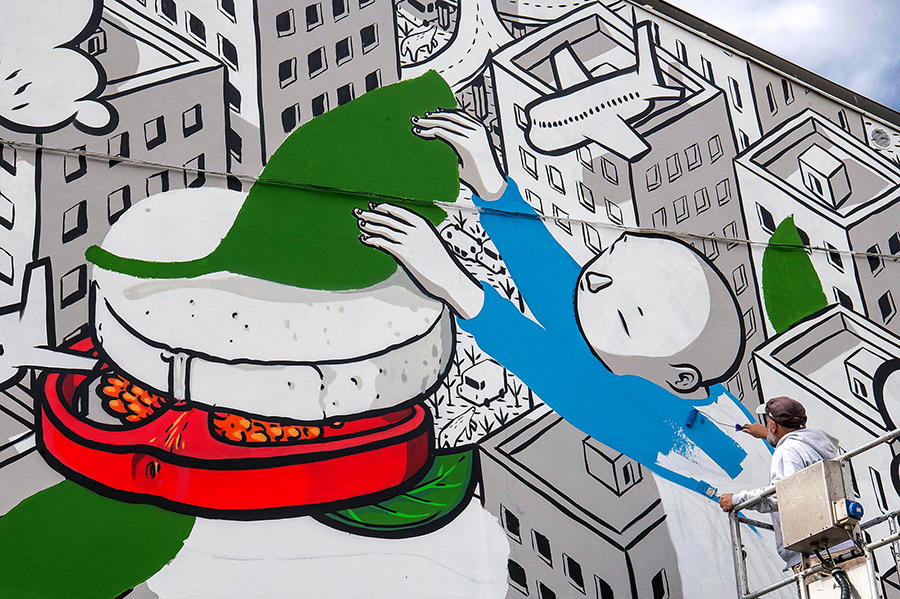

The result: a high-energy, low-profile intervention across San Giovanni Lupatoto and other Verona suburbs. These weren’t “art walks”—they were tactical takeovers. Artists painted four-handed pieces over vandalized walls: CIBO’s flying pizzas alongside Zed1’s surreal characters; asparagus stalks layered with Mantra’s naturalist flourishes. This wasn’t nostalgia—it was public protest, humor, and heart in action.

To ensure the work wouldn’t disappear unnoticed, Martha Cooper—the well-known NYC photographer who helped canonize graffiti with Subway Art—flew in to document it all. Her lens captured not just murals, but the camaraderie, tension, and resilience behind them. Now, over 50 of those photographs are on view at Forte Sofia, Verona, through June 29. Curated by Sara Maira—art strategist and activist—the exhibition is a powerful retelling of a grassroots moment turned collective memory.

We spoke with curator Sara Maira about the festival and the work of CIBO.

BSA: Please tell us about the name of the festival where CIBO collaborated with other artists in Verona?

Sara Maira: The festival and its current exhibition in Verona is called “BEST BEFORE. Street art against a rancid future.” It’s a call to action for the public—an act of artivism initiated by CIBO with the goal of inspiring people to stand up against closed-minded politics, nationalism, and obscurantism before it’s too late.

This is an artivist performance made possible through donations CIBO received over the years from patrons who supported his social commitment against fascism, racism, and hate.

BSA: What attracted CIBO to paint food on public walls? Why choose food as a subject instead of something else?

SM: “CIBO” in Italian is also a nickname for food, so it started as both a joke and a necessity. When he was young, he didn’t have much money to buy paint, so he used leftover colors that other artists didn’t want. Since food comes in almost every color, it became a practical solution. That’s how it began.

As he matured, so did his message. Food evolved into a metaphor—his way of talking about some of the most urgent problems we face today: the rise of neo-fascism and neo-Nazism, nationalism, discrimination, environmental collapse, short-sighted politics, and the widespread social regression we’re seeing worldwide.

He often uses this example: the Caprese salad has the colors of the Italian flag and is considered a traditional Italian dish. But if you examine the ingredients, none are originally Italian. Tomatoes come from Western South America and were first cultivated by the Aztecs. Spanish explorers brought them to Europe in the 1500s. Basil comes from India, and if you add olive oil—as Italians do—it’s originally from Syria. So what we now call “tradition” is actually a product of cultural exchange, migration, and cooperation. If we close our borders and minds, we risk losing that richness.

Every mural CIBO paints contains hidden messages like this. On the surface, it may look like a simple plate of food, but often it’s layered over a swastika or other hate symbol—visually erased but symbolically challenged. What looks colorful and inviting at first glance reveals itself to be part of a much deeper conversation.

BSA: What’s the significance of CIBO painting over hateful or racist messages on public walls?

SM: For him, it’s both an act of resistance and a form of public service. Covering up hate is just one part of his practice, but he sees it as one of the most essential—especially if you consider street art to be public art. This is where public art can make an immediate difference.

CIBO lives in Verona, a city in northern Italy that has long struggled with fascist ideology. That ideology never completely disappeared after WWII, and in recent years it has made a disturbing comeback—not just in Verona, but around the world. At first, CIBO simply responded to what he saw. He had spray cans in hand, he saw hateful messages on walls, and he began covering them up.

Then it became personal. Fifteen years ago, one of his friends was murdered by neo-Nazis. Since then, his work has become a mission—a colorful and peaceful revolution. It’s voluntary activism: an artist giving back to his community, trying to change the world one spray can at a time.

These people are violent; their language is violence. But CIBO’s language is beauty and art—and they’re not prepared for that. Usually, swastikas are covered with opposing political symbols, and the fascists are ready for that. They expect confrontation. But when they’re met with a painted piece of cheese or a slice of pizza, they don’t know how to react. They still come back and vandalize the murals, but CIBO has learned to use their hate as part of his art. He now plans his murals like recipes—every time they come back, he adds an ingredient. Over time, his walls become layered “recipes of resistance,” evolving performances in public space.

In the beginning, people walking by didn’t even notice the hidden messages—there was a sort of visual blindness. But after a few years, people caught on. They realized there was a problem and started sending him photos, asking him to restore or repaint walls. Eventually, some of them started taking action themselves.

BSA: Does CIBO get threatened by the people whose graffiti he covers with food murals?

SM: Yes, he receives threats often. People have sent him death messages. Once, a small bomb was placed on his car. He’s found swastikas painted on his door, and he’s no longer able to move around freely. That’s why he chooses to paint during the day, in public, with people around him. Visibility is his protection. Showing his face is part of his defense strategy.

BSA: Has CIBO gotten into trouble with the police for painting on illegal walls?

SM: Yes, that’s why he works with a lawyer. He’s been reported many times by politicians and law enforcement. But because he’s a recognized artist—and because he’s covering hate symbols—he has never been arrested or convicted.

CIBO X ERON

CIBO X CLET

BSA question for photographer Martha Cooper:

While going through your CIBO/Verona photos, we noticed that the police showed up a couple of times while he was painting with Mantra, and again while he was painting with Clet. Were the police officers hostile to him? Did the officers show up as a routine or were they responding to a complaint from a citizen?

MC: Not sure if the cops showed up because of a complaint or if they were passing by or what. They questioned the artists but allowed them to continue. They weren’t particularly hostile but not exactly friendly. I tried not to let them see I was taking their picture because I wasn’t sure if I was allowed. Cibo is well-known in Verona but he is mostly painting illegally. As I remember, only one of the walls was a permission wall but I don’t remember which one. Almost all of the walls were ones that Cibo had previously painted which had been gone over. One wall says something like “Thank you Fascists” painted by Cibo but I’ve forgotten what the story was. Sometimes the fascists leave Cibo notes. Attached are photos of him peeling off a note which reads “Tu aisegni noi roviniamo!” which, according to Google Translate means “You draw, we ruin”.

CIBO X CLAUDIANO

CIBO X MILLO

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY