The following essay by Steven P. Harrington and Jaime Rojo, co-founders of Brooklyn Street Art, appears in the book “Eloquent Vandals The History of Nuart”, edited by Martyn Reed, Marte Jølbo, and Victoria Bugge Øye and published in 2011 by Kontur Publishing. More information appears after the essay.

Freed from the Wall, Street Art Travels the World

The Internet and the increasing mobility of digital media are playing an integral role in the evolution of Street Art, a revolution in communication effectively transforming it into the first global people’s art movement.

While that may seem hyperbolic, just witness the millions of images of Street Art uploaded on photo sharing sites, the time lapse videos and full length films online, the hundreds of blogs, websites, discussion forums, chatrooms, Facebook pages, Twitter addresses, and phone and tablet apps dedicated entirely or partially to Street Art and graffiti and the multifaceted culture that grows around it. Thousands of people daily are populating the databases, compiling a mountainous archive of something once quaintly referred to as an ephemeral art. This said, the transformative story is that the images are now freed from their sources to float in the ether for anyone with a digital device to access. Within the space of a decade, art that once lived and died on a wall with a local population is now shared via digital capture and upload, gaining access to a worldwide audience. Immediately.

The multi-authored amorphous swirling whirlwind of street art, graffiti, public art, and urban art is simply too vast for any person to get their arms around or explain – yet our digital media tribes are enabling us to collect it, share it, and study it in larger numbers than ever imaginable. As artists and professionals for 25 years in New York, a city with a legacy of graffiti all its own, we have been extremely lucky to witness the blossoming of the current Street Art movement; to document it, analyze it, discuss it, and share it by real world means and virtual means with thousands of others. With the dual forces of high rents and corporate gentrification pounding the final nails into the coffin of the established creative neighborhoods in Manhattan, gritty bubbling new and youthful artist neighborhoods of Brooklyn became de facto showcases for the Street Art scene at the turn of the century, and we were shooting images and tracking its evolution from the beginning.

In concert with the Internet, all manner of art that occurs in the streets is being captured and shared, discussed, critiqued, celebrated or dismissed by people of searing intellect and those who cannot locate their own country with their finger if you spin a globe in front of them. As text has been loosed from print in this post Gutenberg Parenthesis world of Sauerberg, so too our local Street Art is freed from its wall. Going from “All City” to “All Timezones” has radically transformed how Street Artists perceive their work and their audience, with the concept of “place” profoundly altered.

Nuart became a focal point for many in the Street Art world in the early 2000s because of its highly curated nature and its expansive brand of personal interaction with public space. A hybrid of high-minded civic involvement and an art form with roots solidly in anti-authoritarianism, Nuart has presented a rolling roster of Internet stars and miscreants of the Street Art scene. It’s a highly unusual mix: quality experimental elements birthed by the interconnectedness of the virtual world, soon imitated by other entrepreneurial Street Art enthusiasts. With the help of the Internet this Norwegian port town of Stavanger is an international player in the Street Art scene, a by-invitation celebration capable of drawing a wide range of serious talent to create epic pieces in singular locations. When the images and videos of installations at Nuart are relayed through the forums and chatrooms and blogs and Flickr pages around the world, other cities begin rethinking public space and examining with a new interest the players in their own Street Art scene.

A large part of our understanding of art and its expression for generations has come from textbooks, lorded over by scholars and experts who were trained by others using similar texts passing along received knowledge and prejudices. For those rebels of the graffiti and Street Art movement who have never given much credence to formal education, the unbound and chaotic nature of digital communications actually feels more organic and trustworthy. In large part, with the exception of the formalism of the logical structure comprising the undergirding of the Internet, its explosive growth has been more intuitive and behavioral than left-brained or hierarchical. The beauty of a new Street Art piece on a nearby wall is electrifying to share with the digital tribe, and in so doing, it legitimizes ones status among peers and the work of the artist as well. With the innate desire to learn being regularly quenched by members of this tribe, collective intelligence is rising more quickly than any organized curricula could ever aspire.

Image Capture, Sharing, and Platforms

Graffiti and Street Artists have always benefitted from documentation of photographers like John Naar, Keith Baugh, Martha Cooper, Henry Chalfant, and James Prigoff, who are largely responsible for the capture and preservation of the historical knowledge we now have of graffiti in New York City during the 1970s and 1980s. Without the benefit of instant communication of these images, copies of Cooper and Chalfant’s book Subway Art and Charlie Ahearn’s movie Wild Style relied upon actual physical distribution channels and commerce to travel around the world and inspire young artists. “Viral” was a word associated with antibiotics.

As film turned to digital at the turn of the century and cameras and personal computers became far more affordable, the convergence of technology gave professional and amateur photographers the incentive to roam the streets hunting for street art and the ability to have the instant gratification of seeing their photos online. As in the early days of graffiti, Street Artists of the 2000s didn’t shy away from the attention photographers were giving to their work and a new symbiotic relationship between the street artists and web savvy photographers was born where certain artists would place their work where it was likely to be seen and photographed, and hopefully distributed online. Like the days of Cooper et al., digital photographers assisted many of the current stars of Street Art to gain exposure to an appreciative fan base and to increase their popularity during the decade.

With the introduction of the online image-sharing platform called Flickr in 2004, the already rapid spread of Street Art photography completely ballooned as fans from every city and town and hamlet began uploading their Street Art images to one location where everyone could coalesce around their common interest. With a database structure and system for tagging, images could be categorized, sorted and most importantly, searched. No longer reliant on the approval of gatekeepers or site curators, Street Artists gained autonomy and audience largely on their own terms and with the help of photographers who scoured the streets to capture their work. Of the current 6 billion or so images uploaded to the site since then, millions are of street art – a de facto common repository and shared research archive for artists, professionals, curators, collectors, and casual fans.

A new central nervous system in formation, Flickr and other lesser-known sharing platforms had a profound causational relationship to the dissemination of Street Art culture to a worldwide audience. You knew Melbourne and Bristol and São Paulo and New York had a Street Art scene, but Sacramento? Shanghai? Stavanger? In addition to images and videos, the platform provided common space for exchange of opinion, ideas, and news, fostering online and offline relationships and enabling Street Artists and photographers to pursue their work as a possible career route.

Photo sharing sites of course are not the only means for the worldwide distribution and formation of a common understanding of Street Art culture. Today’s digital biosphere includes primary content sites and blogs, aggregators (or self-described “curators”), peer-to-peer forums, Social Media, and mobile apps as part of the overall knowledge base, forming an increasingly common understanding about Street Art, it’s origins and it’s evolving expression in the public sphere. No one can doubt that this familiarity has only aided its popularity.

In one significant role-reversal, the online experience of Street Art has also altered the behaviors on the streets and once sacrosanct “rules” of the street have been turned on their head. Although it was once verboten to reveal a street location for fear of reprisal, now both street artists and fans geotag their images so they can be found on a map with any GPS enabled device. As mobile device use eclipses Internet use in the next couple of years and hardware and software becomes more flexible, sophisticated, affordable, and available, there is no doubt that more apps and platforms using mapping and GPS are likely to thrive. Whether through image sharing platforms or mobile apps, these systems of tagging are providing exact information for self-guided tours by fans and tour groups, peers, enemies, and of course, law enforcement.

Excerpts from additional subtopics of this essay:

Tribes and Co-Surveillance

“The growth of connectivity is producing a foundational change to the world of the Street Artist and his or her relation to society as a hidden and/or marginalized figure. Increasingly it appears that it is impossible to be socially isolated when you are so busy relating, even if anonymously. Unwittingly, the stereotypical vision of the outsider is melting as one is pulled into a collective environment where peers regulate and monitor the actions of one another and settle disputes or give encouragement and opportunities. The new digital world, once thought to be impersonal, is increasingly fluid, intuitive, and connected; enabling a near eradication of feelings of estrangement, ostracization, marginalization, and isolation for many people, Street Artists included.”

Reaching an Audience

“Arguably the act of spraying a tag or signing your name to your art can be called advertising or at the very least, branding; A Street Art purist who rejects any ideas of the advertising taint may instead put their work on the bottom side of a railroad tie, but we haven’t heard of it. Everyone understands that the primary motivation is to have one’s work seen, and thanks to the Internet and digital media, an ever-growing sophistication in self marketing is on display from Street Artists who are adept at making art, and even those who are not.”

Democratization, Homogenization and Gate Keepers No More

“A certain homogenization of recurring styles, techniques, and themes due to mass disbursement also has begun, creating certain elements of an international style with clearly traced antecedents. A common language, vocabulary, and terminology that began with print media and graffiti continues to grow and refine itself. An international galaxy of galleries and festivals, and increasingly, museums, expands and contracts with lists of overlapping names traveling from continent to continent in search of walls. Listed after the artist’s name in parenthesis is the abbreviation of their country but in practice the Internet has quickly enabled them to become virtually stateless. Thanks to instant availability, a 14 year old in a sleepy small town is schooling himself with YouTube right now and with luck and skill will inherit that state as well.”

~ Steven P. Harrington and Jaime Rojo, co-founders of Brooklyn Street Art

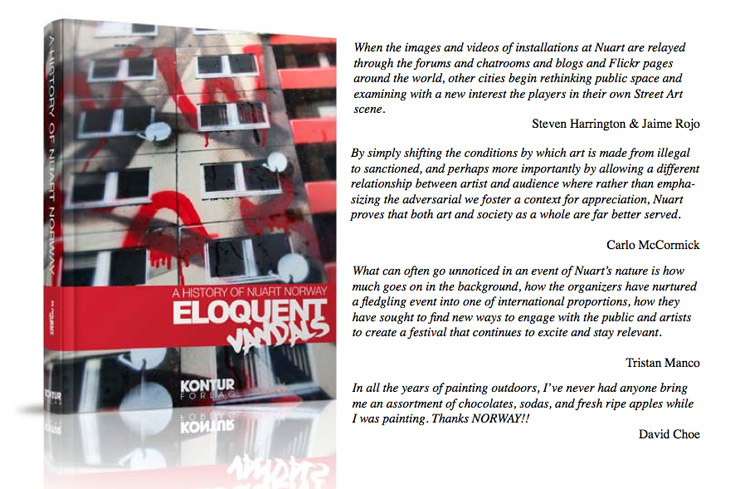

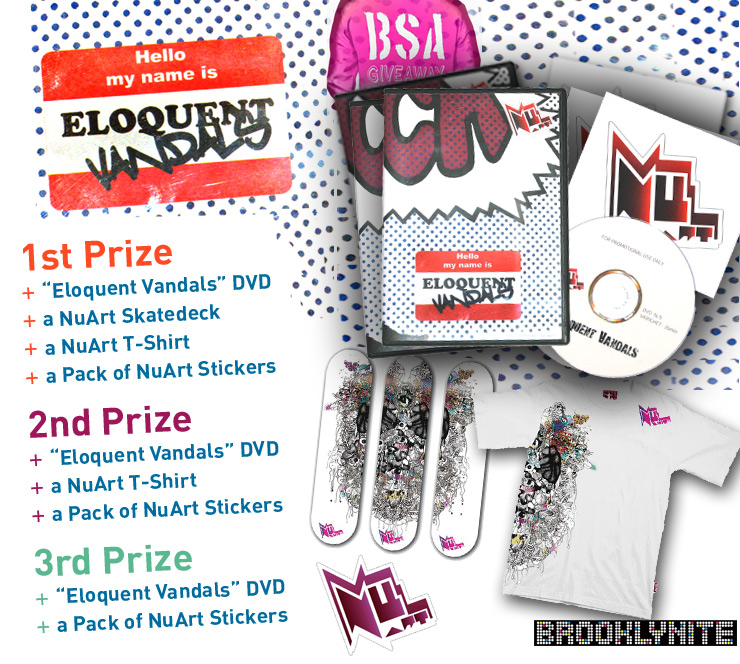

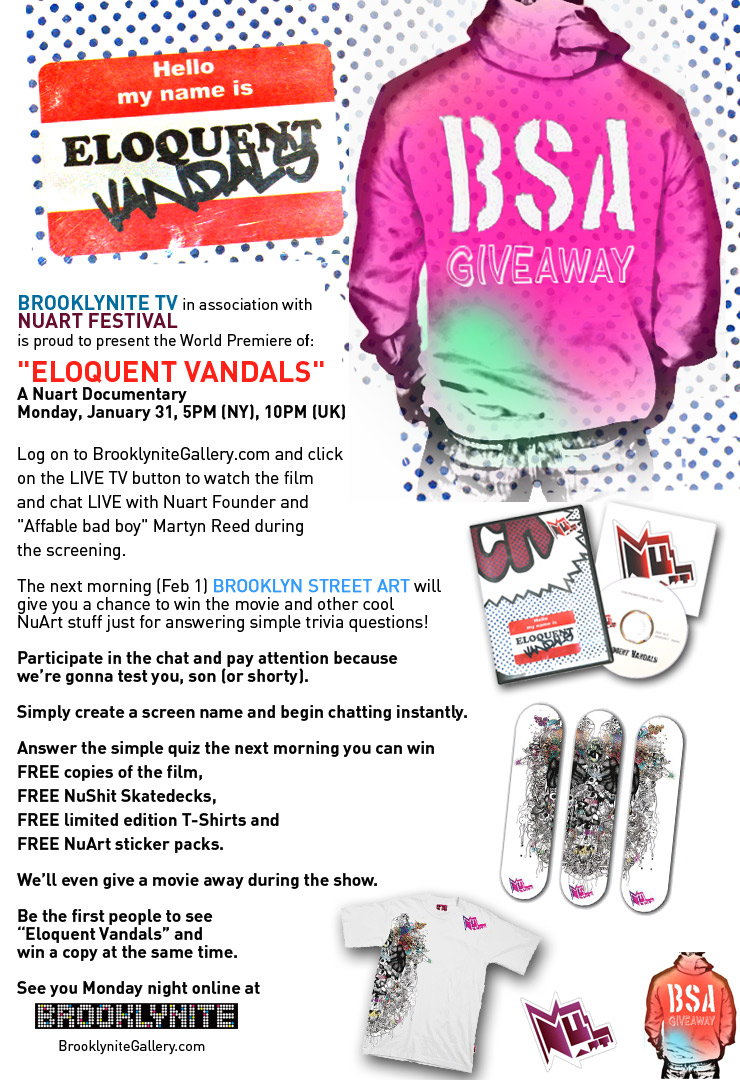

Read the full essay in:

ELOQUENT VANDALS “THE HISTORY OF NUART”

Available Internationally on Amazon

Buy Now, Norwegian : Platekompaniet

Editors: Martyn Reed, Marte Jølbo, Victoria Bugge Øye,

Features: 304 Pages, full colour, hardcover

Format: 21 x 26cm

Language: English & Norwegian

Publisher : Kontur Publishing

Eloquent Vandals is the definitive book on one of the worlds leading street art festivals featuring exclusive essays from some of scene’s biggest names. Over 300 pages of exclusive images including works by Swoon, Brad Downey, David Choe, Vhils, Blu, Ericailcane, Logan Hicks, Dface, Nick Walker, Judith Supine, Graffiti Research Lab, Blek Le Rat and many more…

Eloquent Vandals tells the story of how Stavanger, a small city on the West Coast of Norway gained a global reputation for Street Art. For the past six years, the annual Nuart Festival has invited an international team of Street Artists to use the city as their canvas. From tiny stencils and stickers to building sized murals, from illicit wheat-paste posters on the outskirts of the city to “Landmark“ pieces downtown, found everywhere from run down dwellings and train sidings to the city’s leading galleries and fine art institutions, Eloquent Vandals documents the development of not only Nuart, but also one of the most exciting art movements of our times.

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY