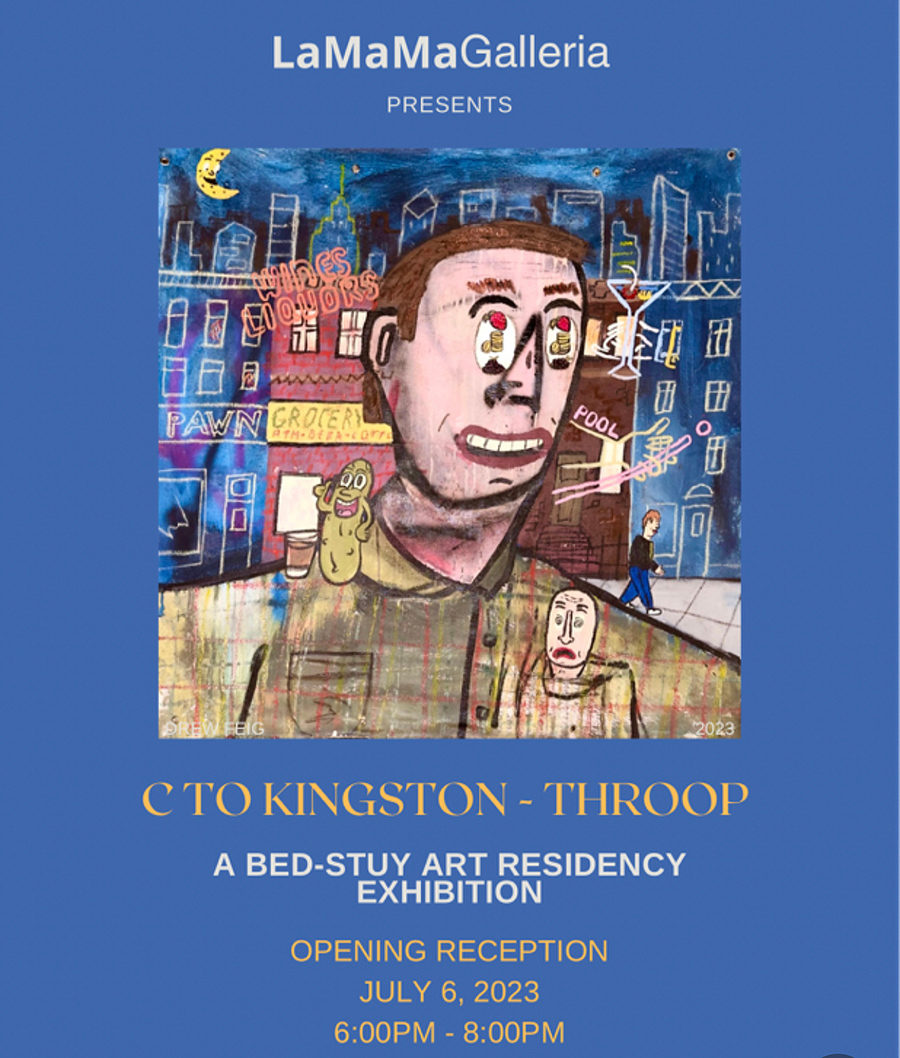

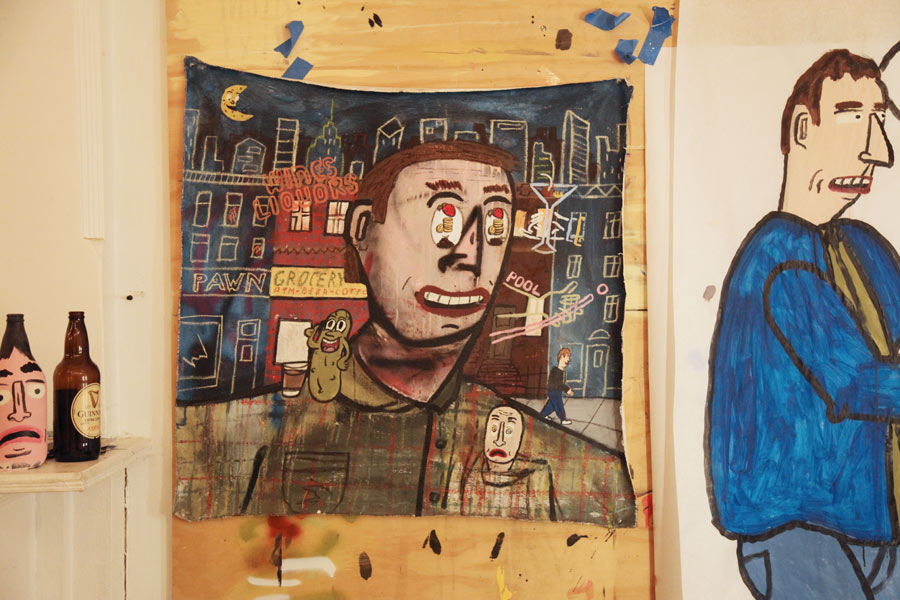

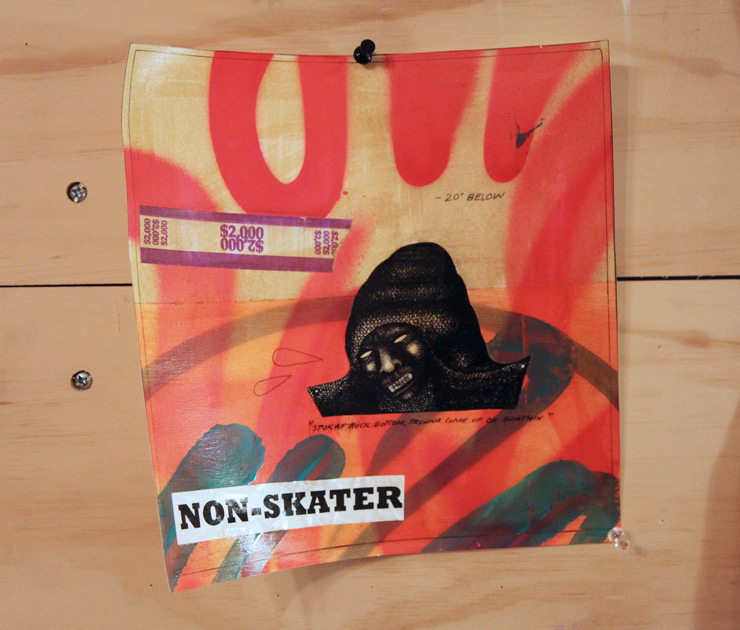

“There are a lot of royalty here with all these crowns,” we observe scanning over the fresh works taped and stuck to the walls in the front room of this Brooklyn brownstone at the Bedstuy Art Residency.

“Yes I’m always championing the underdog,” says Carlos Ramirez. “I’m kind of rooting for them.”

Half of the artist duo The Date Farmers with Armando Lerma and formerly an actual date farmer in the Coachella Valley in Indio, California, he knows what it is like to be an underdog.

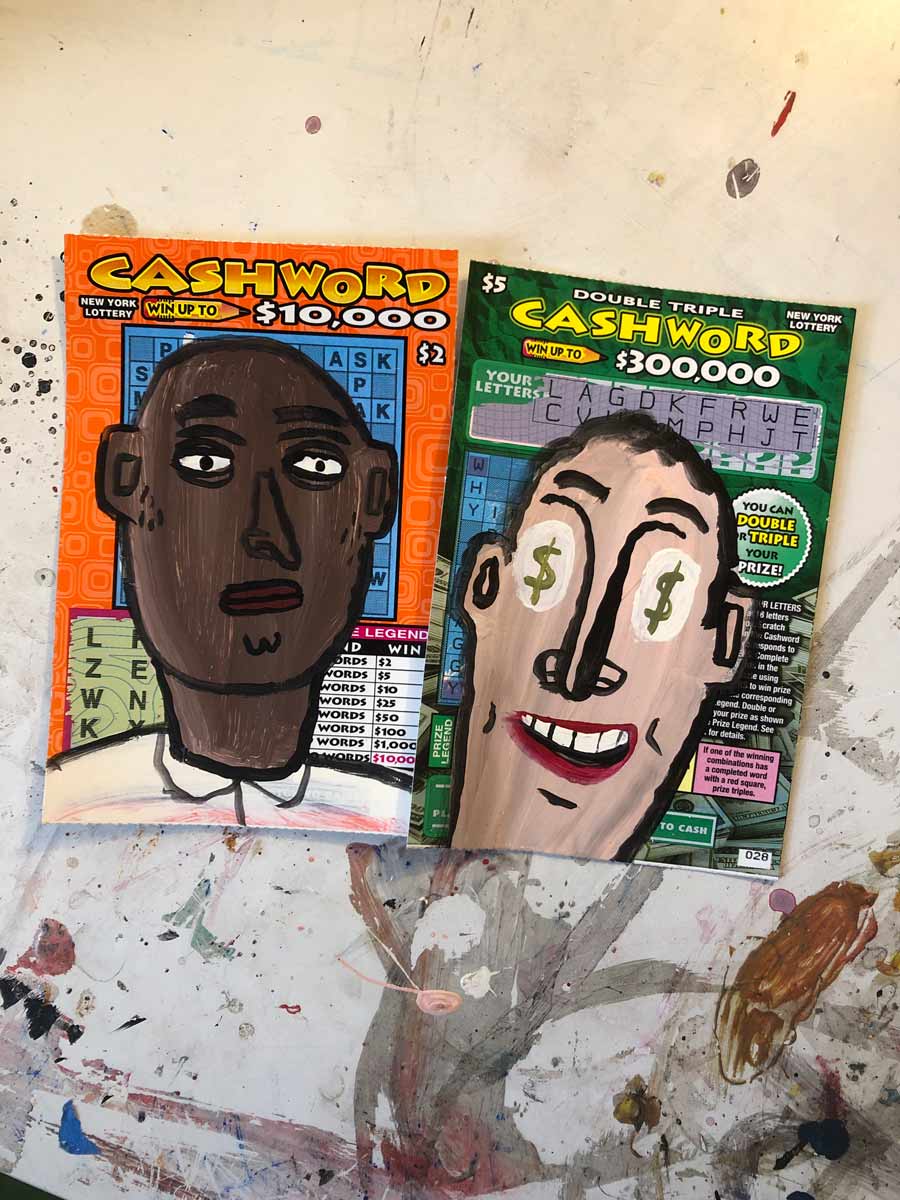

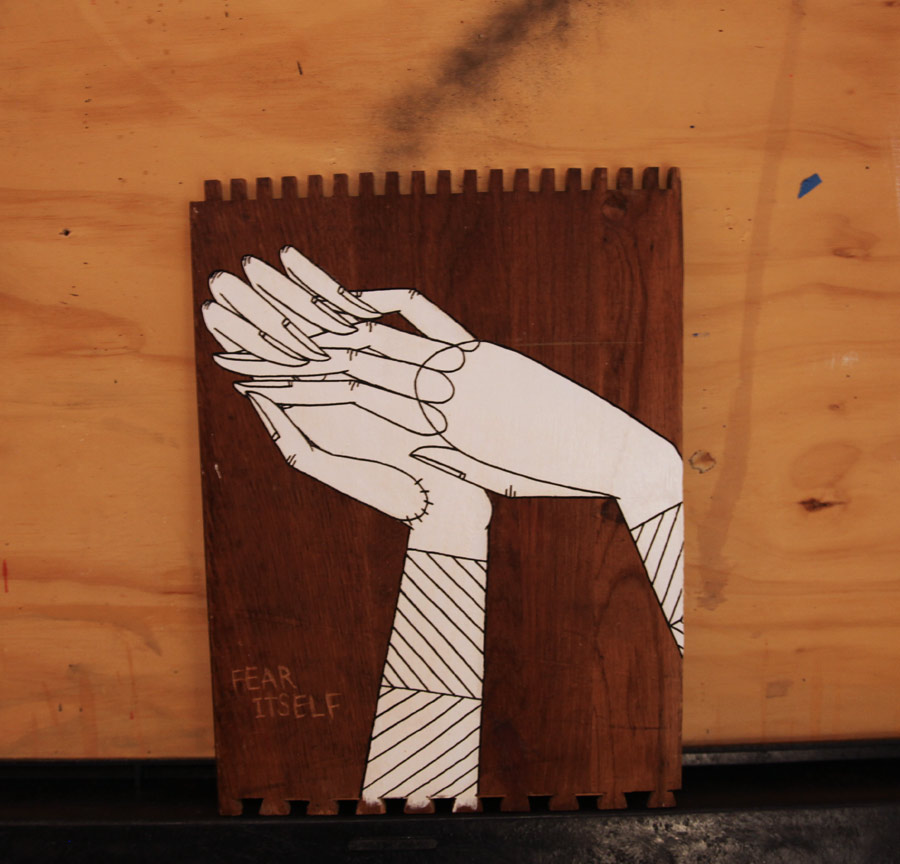

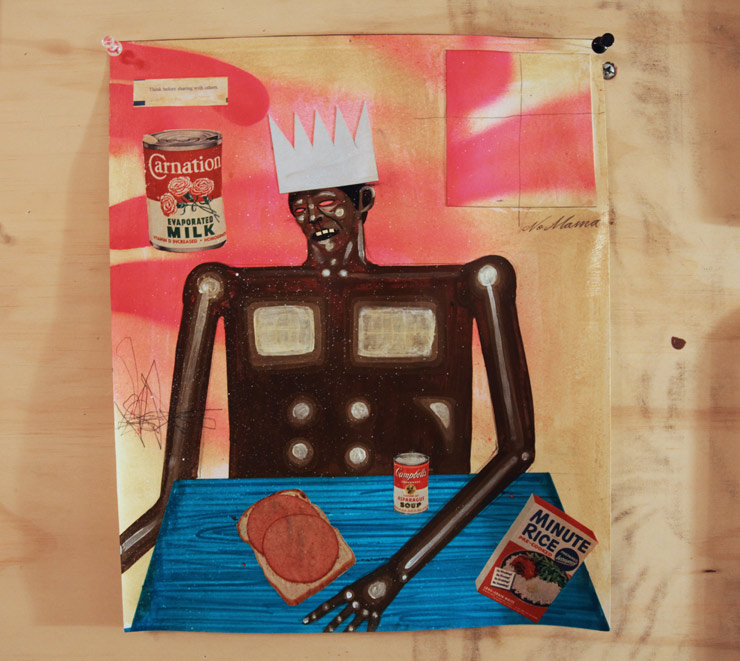

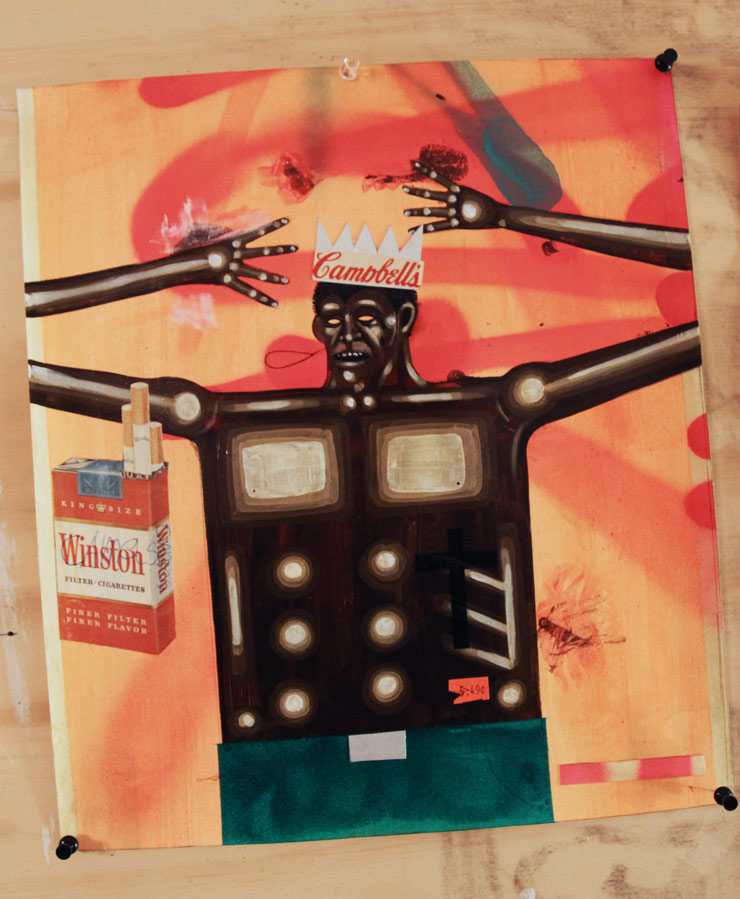

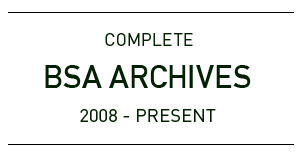

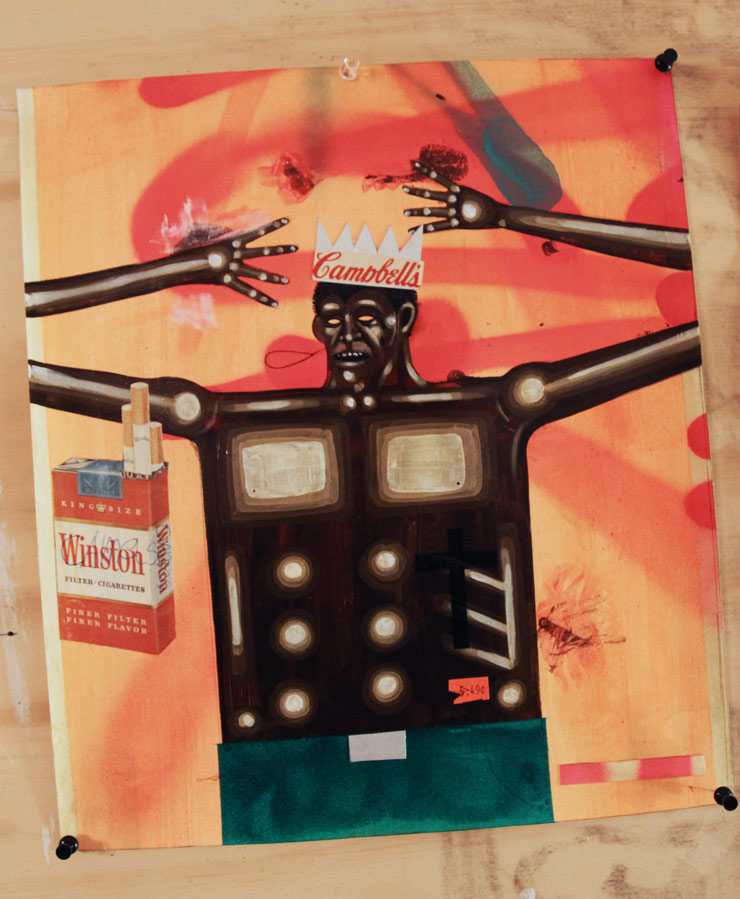

The symbols of power are around the room on these medium sized canvasses and small objects newly painted and collaged with hand-rendered figures and re-purposed logos. The 2-D crown sits jauntily atop the head of a man at a kitchen table that is scattered sparsely with a baloney sandwich, a can of Campbell’s soup, a box of Minute Rice. Probably not a king, Carlos wants this guy to feel empowered.

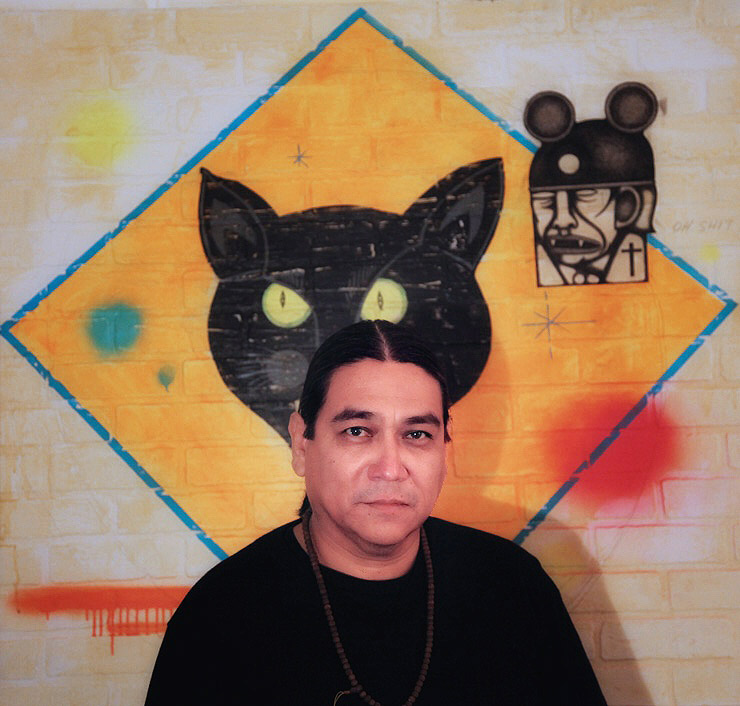

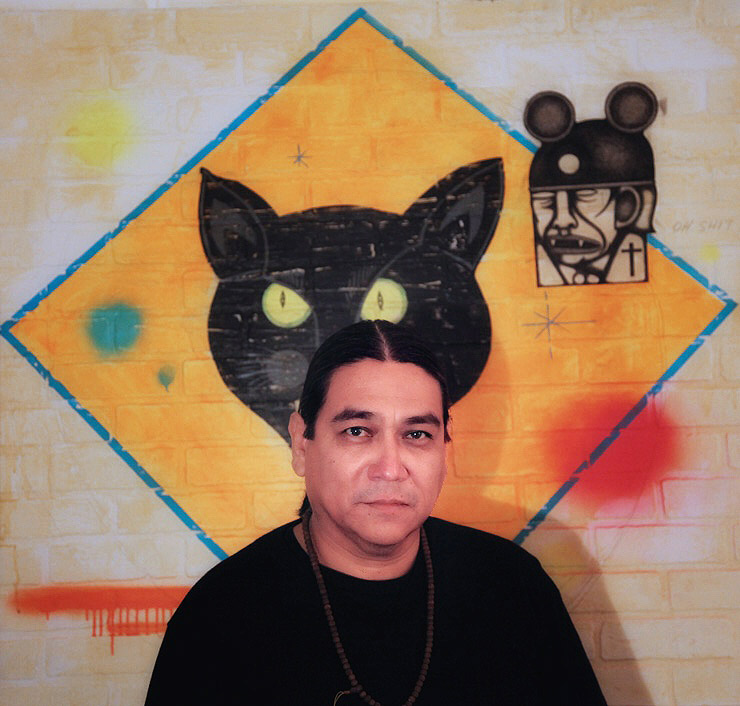

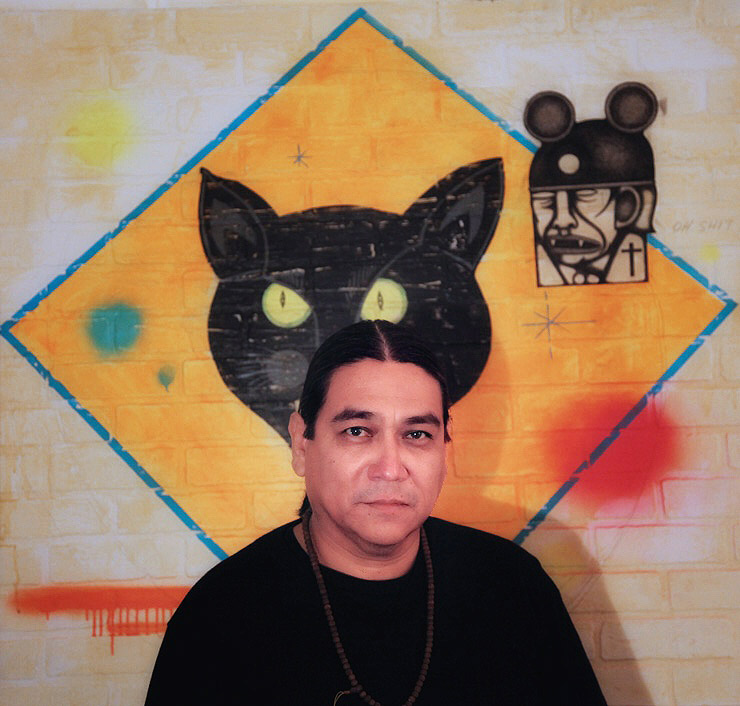

Carlos Ramirez. Bedstuy Art Residency. Februray 2018. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

“This is called ‘Cold Ass Soup’, he explains. “That has to do with latchkey kids who sit at home because you see them everywhere and my attention has always been drawn to that. Because what do these kids do, you know?” His familiarity with the term latchkey, which means a child who is often left at home with little parental supervision, relates strongly into his own experiences as a youth.

A Mexican-American, or Chicano, kid in the 1970s and 80s, the artist says he remembers what he did when he was left alone while his mom worked as a migrant agricultural employee picking produce in the fields. He entertained himself with daydreams and games, sometimes played with other kids, and he drew. Discovering this innate attraction and possible talent, drawing would become an increased focus for him over time, eventually opening doors – even though friends and family didn’t necessarily think much of it then, or even now.

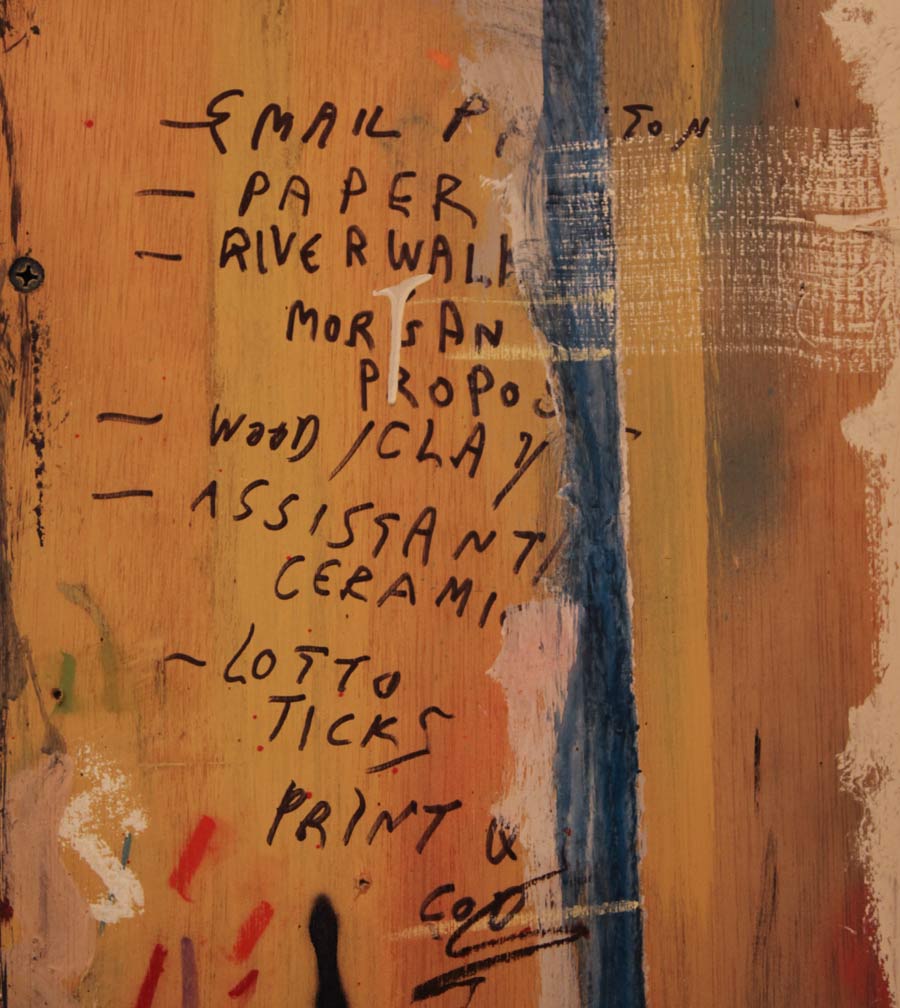

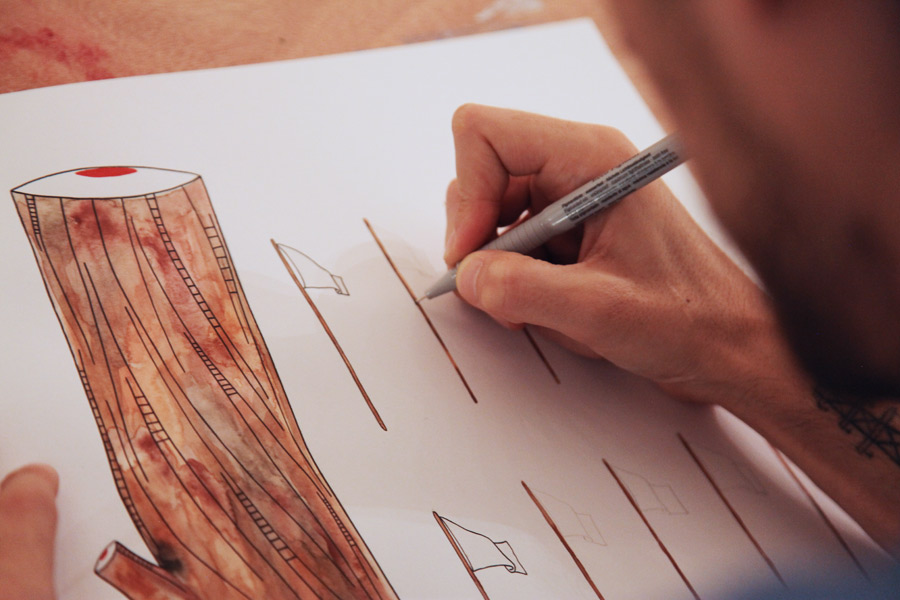

Carlos Ramirez. Work in progress. Bedstuy Art Residency. Februray 2018. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

“I think it was a combination of two things. When I used to go to the fields with my mom and I had to wait in the car like eight hours there were these old books like drawing books with an Indian chief on the cover or something and sometimes she was gone and I would be drawing for hours,” he says.

“She would come and check on me and she would say “oh that looks good” and she would encourage it. I think she was encouraging it so that I would sit my ass there — and then she realized that I guess I had talent or something and I just never stopped.”

Neither did the hard times. Remembrances and stories include drug and alcohol abuse, violence in the home and community, serious health issues and suffering, and long periods of time with very little money, sometimes very little food. With and without specifics, Carlos describes a lot of the situations that he and his family went through as “crazy shit,” possibly because it was confusing and hard to understand for a child, or because it is too painful to recollect the details today.

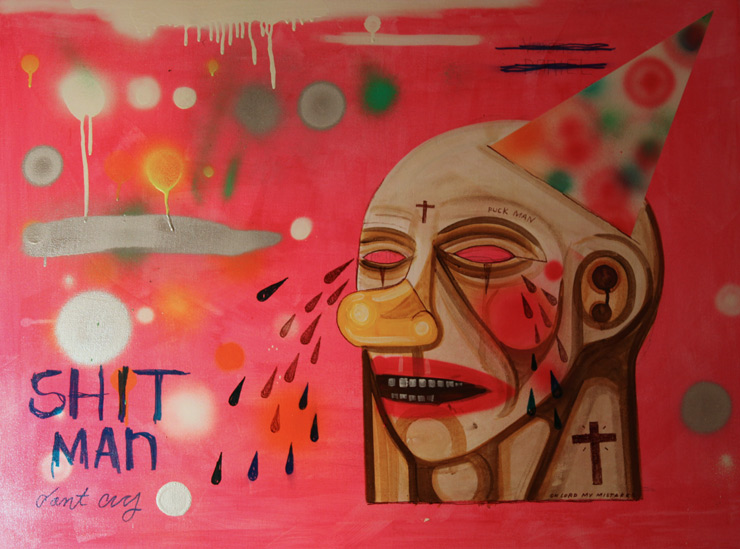

Carlos Ramirez. Detail. Bedstuy Art Residency. Februray 2018. (photo © Jaime Rojo) Refugees adrift, at the foot of the cross. “Life” is now “Lie”.

But the image of Jesus was always there on the walls, or at least the cross was – which is why that influence of Christianity is frequently mixing with Mexican pop culture, Low Rider aesthetics, street culture, Disney, clowns, devils, and the language of commercial advertising in his visual metaphors. Throughout are signifiers of power, influence, and the randomness of modern life that leaves many of us feeling uprooted and listing.

Would he say that he is into religion? “Yeah I believe it. I’m not too into it but I know that there is a greater power,” he says. Later on the topic of the image of Jesus at home and in the church, he says, “I’m not really religious but he kind of represents hope. I would see people kneel, you know. I didn’t know what hope was. Like troubled minds and troubled hearts and all that stuff – it wasn’t till I got older”.

Carlos Ramirez. Bedstuy Art Residency. Februray 2018. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

The concepts of good and evil and an interest in spiritual or mystic topics all appear periodically in the conversation, like the cell phone videos of UFOs in the sky over his home in recent years, or his necklace orbs that represent the distance of the earth from the sun, and a recent mind-body-spirit experience he had in Brooklyn with his mate Jeannette at a “sound bath” with Sound Practitioner Franck Raharinosy who guided visitors using music and hand-rendered auditory journeys performed while they lay quietly on mats.

“He started playing all these different instruments but when your eyes are closed you start to see all these patterns. I don’t even know what he used but it’s different frequencies, and I swear to you I started seeing patterns and I thought ‘Is that normal?’ I have never seen these – we saw colors, patterns …” he recalls.

Carlos Ramirez. Detail. Bedstuy Art Residency. Februray 2018. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

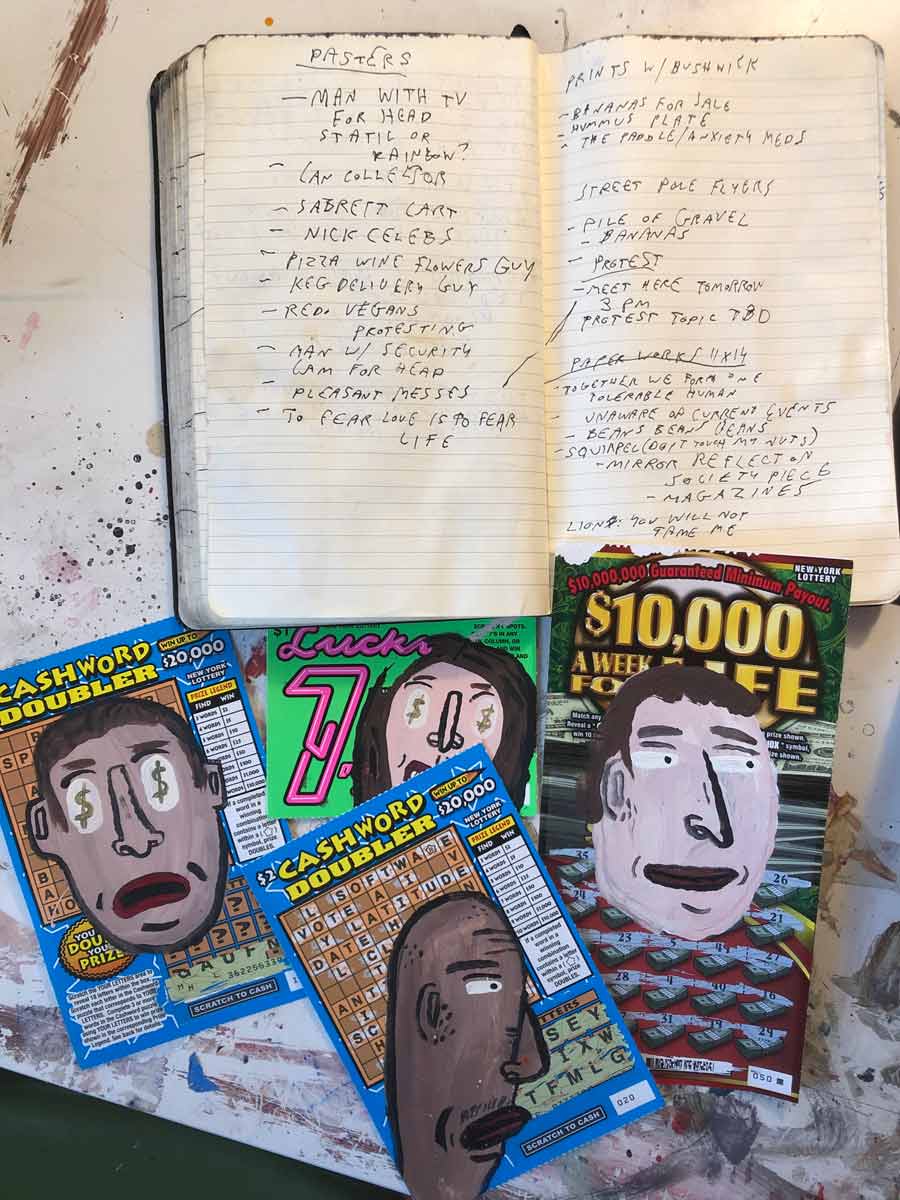

Talk turns to how the Date Farmers began as an official art duo when gallery owner and alt-art visionary Marsea Goldberg gave them the name. The two had had a little luck in their hometown selling work but tripped two hours to Los Angeles to basically walk their artworks around to galleries in their hands. He says that they’ve been working closely with Marsea since the mid 2000s but their personal and professional relationship dates back to those first days in the late 90s when she encouraged them to challenge themselves and to continue making more art.

“I named them, gave them their first show, wrote texts and books about them and I love them,” she tells us at a Brendan Fagen gallery opening this week in New York. Both the Farmers and Fagan (the artist formerly known as Judith Supine) are two of Goldberg’s genius picks whom she shepherded with her New Image Art gallery in LA while they were early in their careers along with other near-iconic or now-iconic names in Street Art/graffiti/Urban Contemporary art like Bäst, Ed Templeton, Barry McGee, Shepard Fairey, Chris Johanson, Anthony Lister, Neck Face, Cleon Peterson, and Retna.

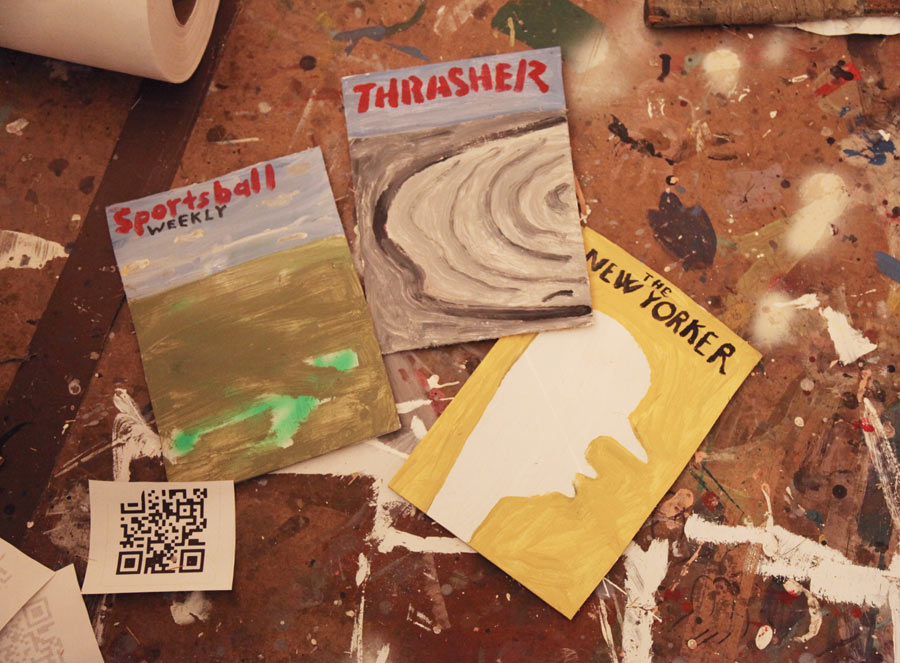

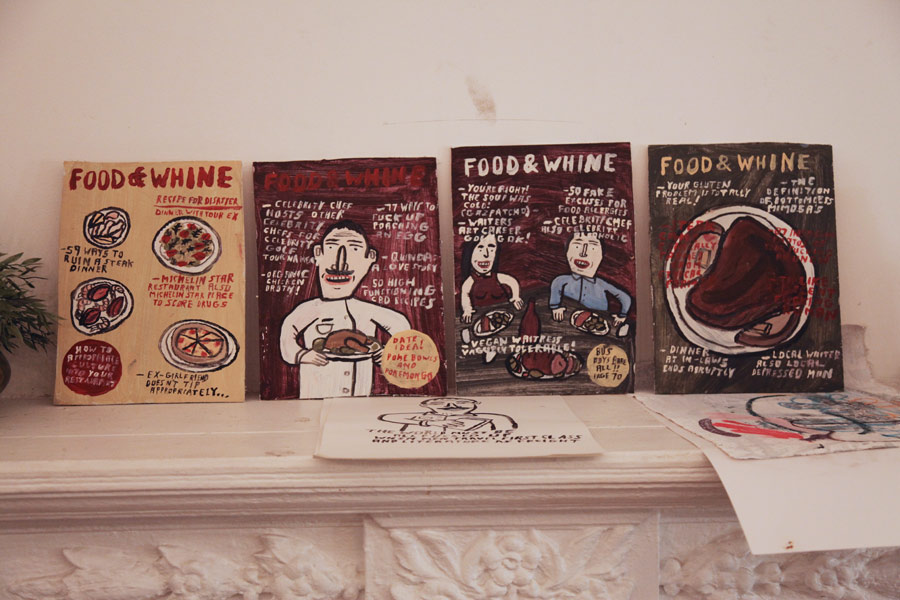

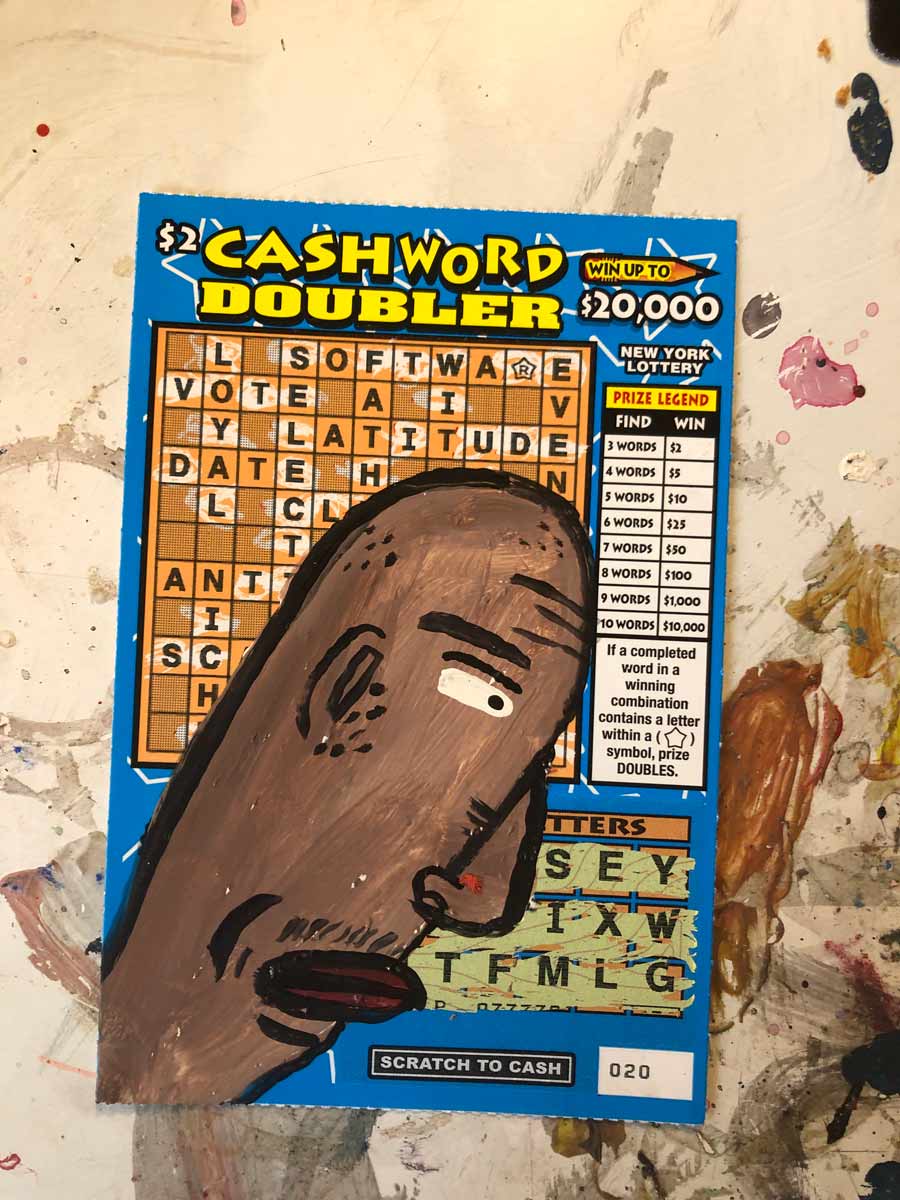

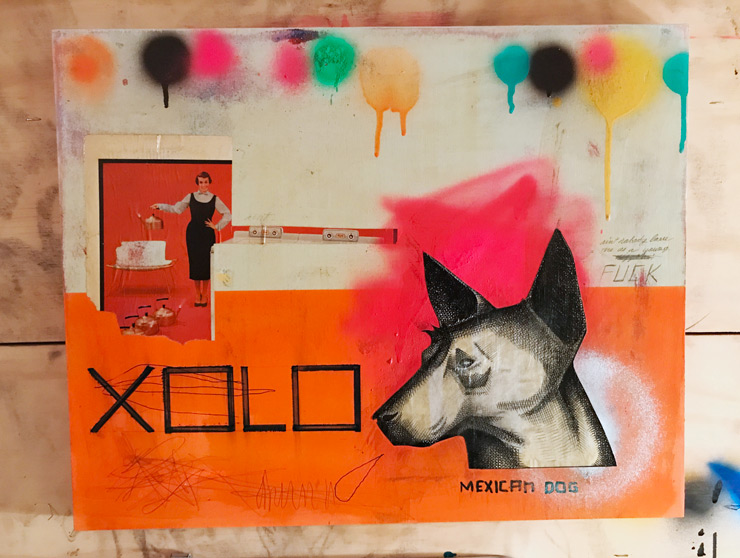

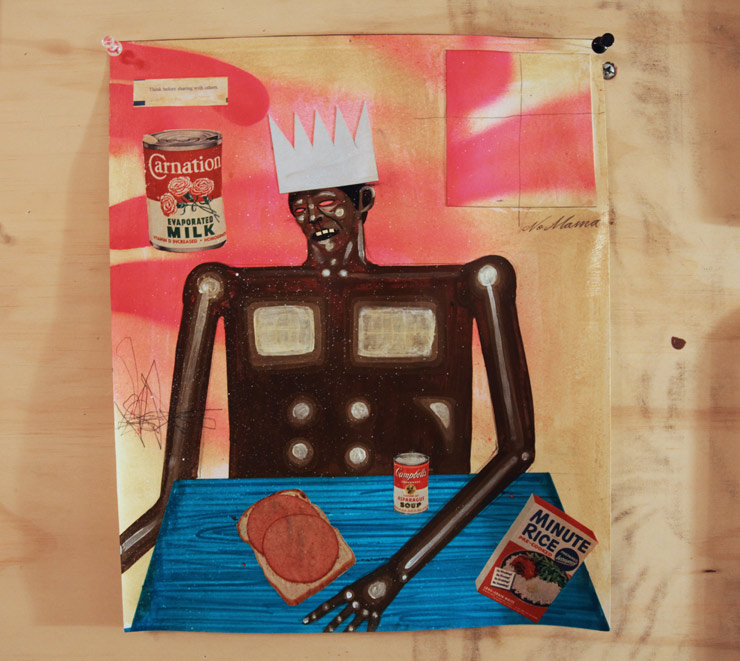

“This is a weird-ass black cat,” Carlos says of the midnight colored feline looking at you from his current canvas-in-process.

What is the black cat doing? “He is selling fireworks,” he says, referring to the logo he lifted from the oldest maker of fire crackers, sparklers, and bottle rockets in the US. “I kind of just took the words out,” he says, “It’s not done.”

Carlos Ramirez. Bedstuy Art Residency. Februray 2018. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

BSA: So you like to strip away the words?

Carlos: Yeah it’s kind of like composing with images. It’s a weird process, like random – like a scan.

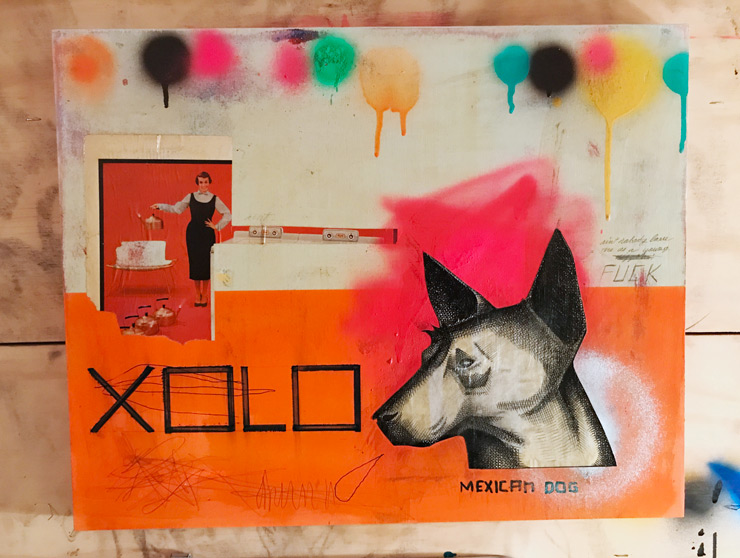

“Where do these images come from – like this guy with the horns?” we ask him. “Do Mexican wrestlers and demonic influences influence you?”

“They’re kind of bad kids you know,” he says gesturing to an old beer can with a densely drawn face glued onto it. “When kids drink they start doing evil shit and so this is kind of more symbolic to kind of say ‘oh here’s a fucked up kid’ – so I put like little horns on him. Obviously he’s wearing Mickey Mouse ears and smoking – stupid kid.”

Carlos Ramirez. Bedstuy Art Residency. Februray 2018. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

And the kid next to the fireworks black cat? Is he bad too? “Yeah you know fireworks … this is like – well, it’s a bad person and he needs to repent.”

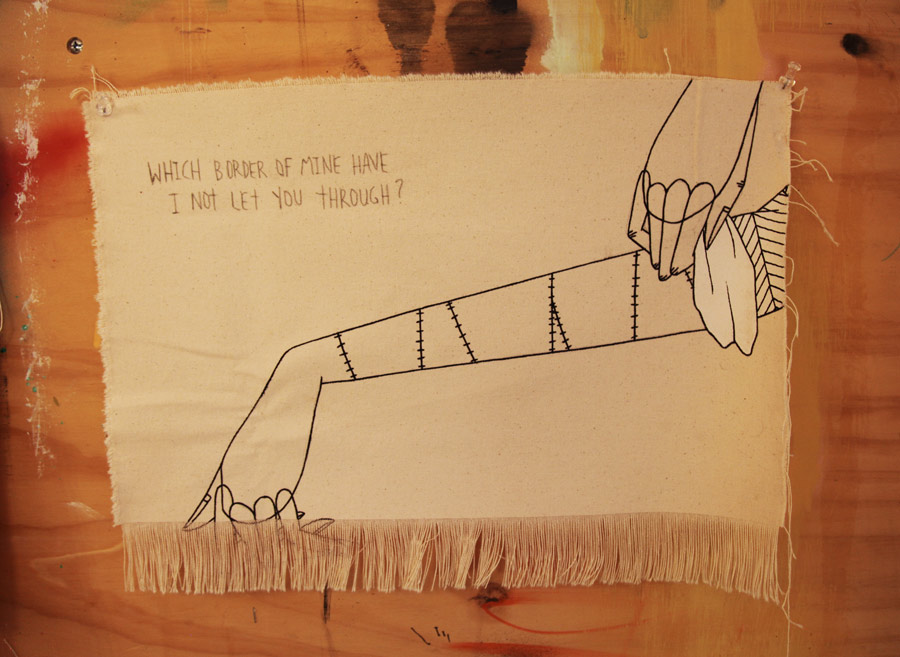

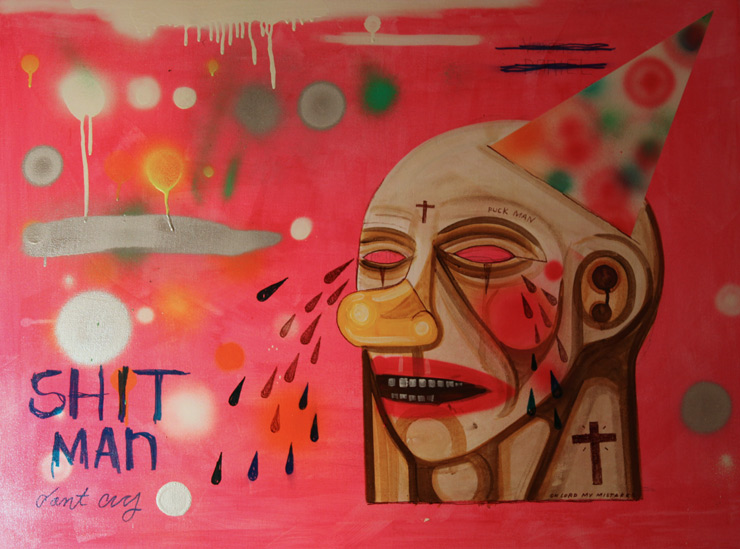

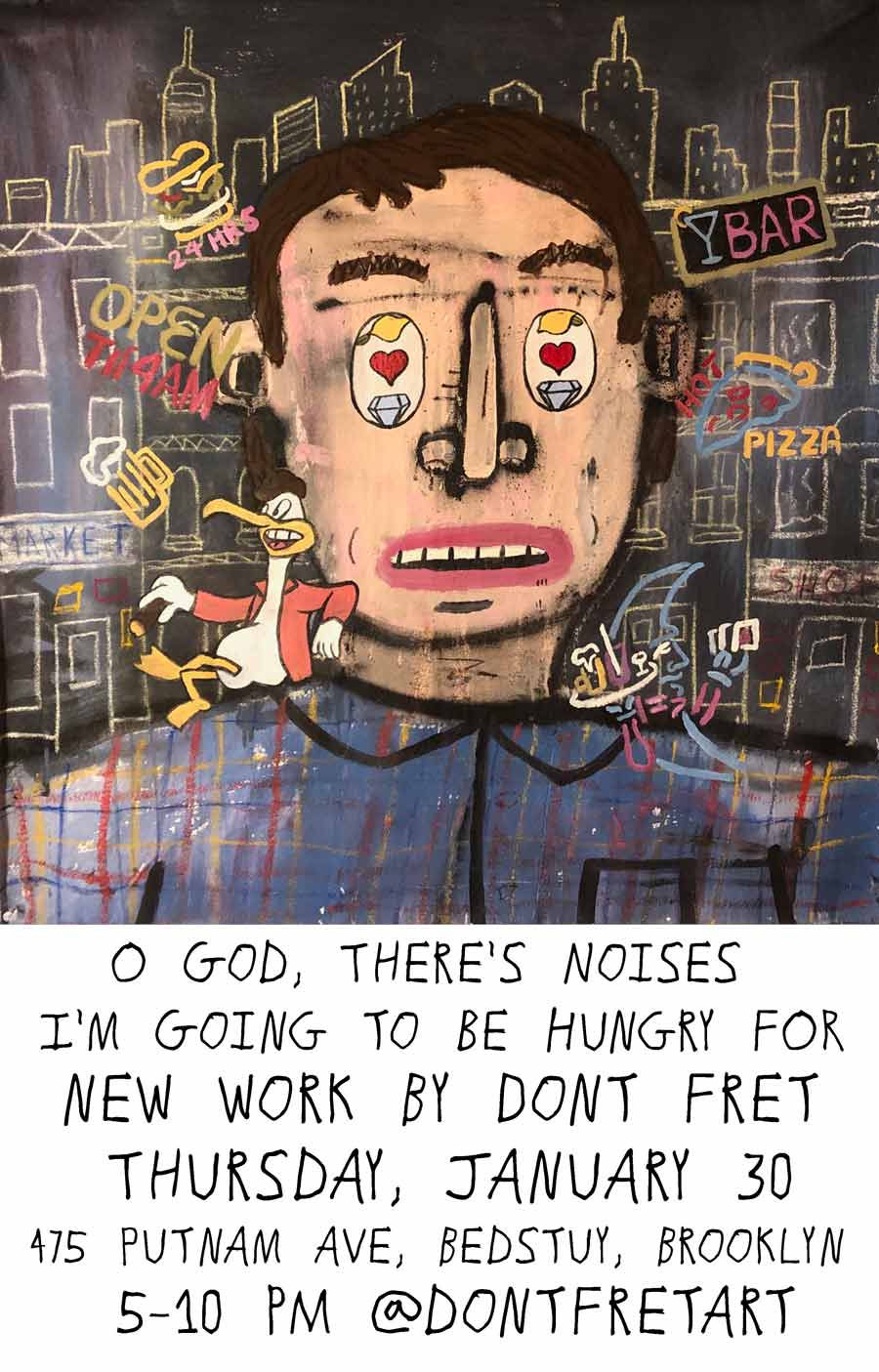

The figures are dark, heavy, labored, square shouldered and square jawed. Backgrounds are Mexican candy-colored pinks, yellows. The color contrast is emblematic of the lives of people he’s known in Mexico and those who have moved to the US; an insistence on optimism and humor in the face of institutionalized racism, social inequality, police abuse, and economic injustice. Again and again he describes the ebullient sense of humor seen across the culture as a pragmatic tool for psychological and spiritual survival.

Carlos Ramirez. Bedstuy Art Residency. Februray 2018. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

Clearly, he is a survivor himself, one whose mother worked for/with the American labor leader and civil rights activist Cesar Chavez in the late 1960s and 1970s, fighting for the rights of grape harvesters, among others. Even during some of the darkest days, including those when Chavez stayed in their home as part of an elaborate house-hopping scheme to escape being killed, Carlos recognized that his mother and his culture knew how to find ways to persevere and to be optimistic in a way that stems from Mexican roots and history.

“When I went out to places like Chiapas I noticed all these colors and it kind of represents their humor and how they can laugh at so much. And it’s not that they’re being cold – it’s just survival. They have seen so much that they are like ‘let’s use bright colors’ so they can keep their sense of humor – it’s some weird shit but I love it, man.”

Carlos Ramirez. Bedstuy Art Residency. Februray 2018. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

We ask why the figures are always dark, dense, strong, and inflexible-looking. His answer makes you realize how hard one has to become to survive sometimes.

“When I grew up if you were kind of like bummed out or sad they would look at you and say ‘Cut that shit out,” like “Knock that shit off.”

“And if I went to my mom and said my leg hurt she would fucking hit you with a belt on the other leg,” he says only half-joking, “to make it hurt more – then you could realize that your other leg didn’t really hurt”

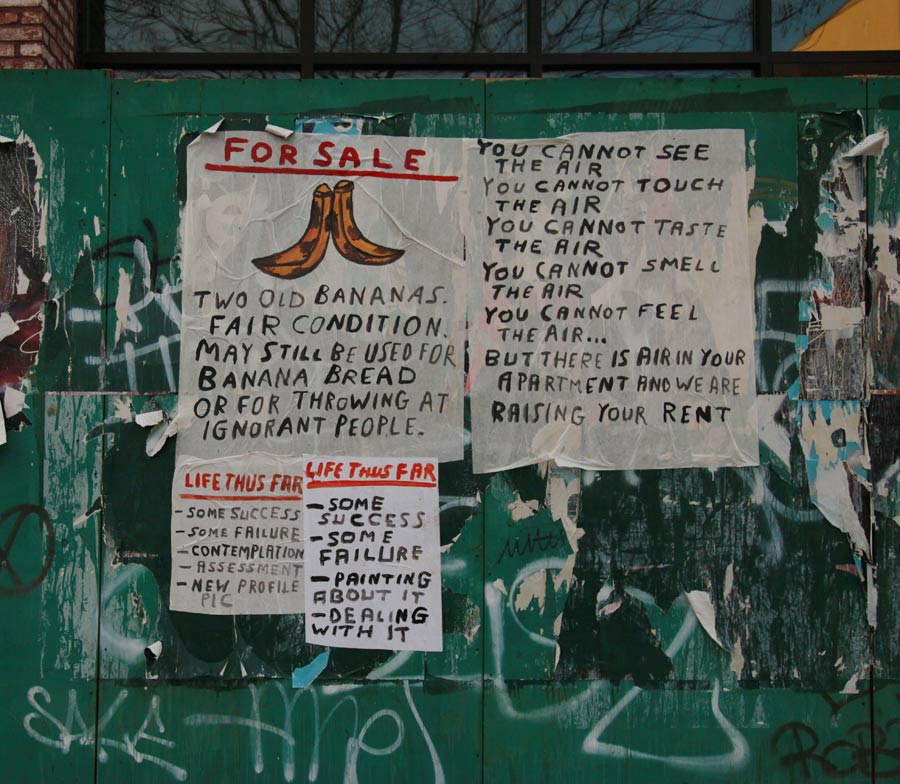

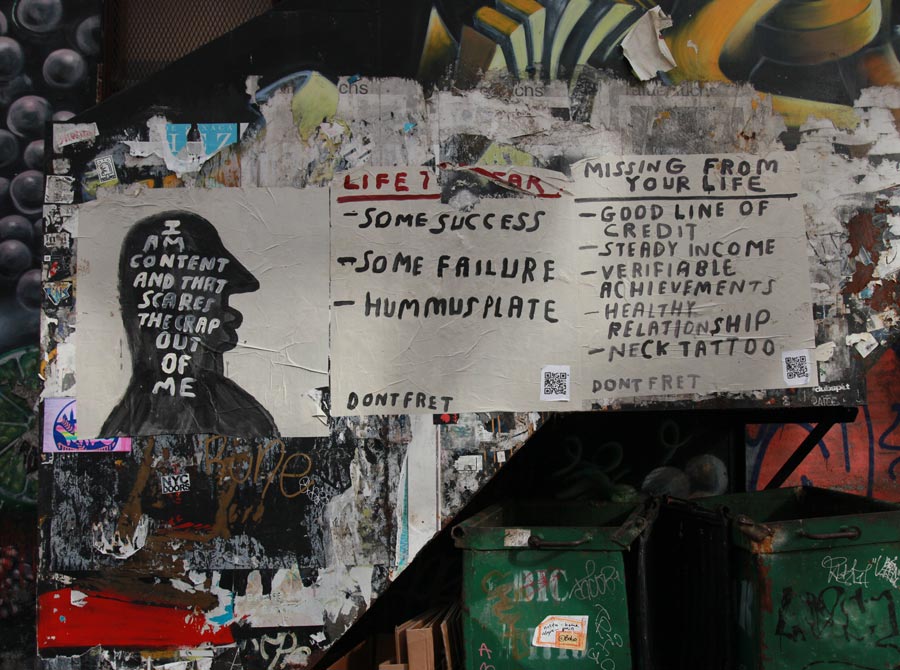

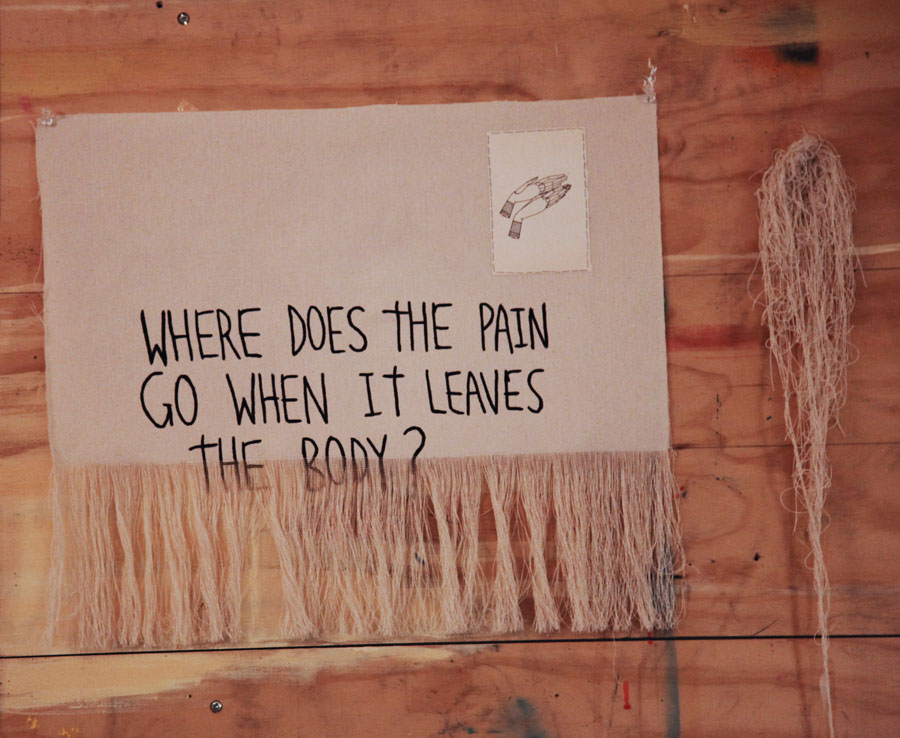

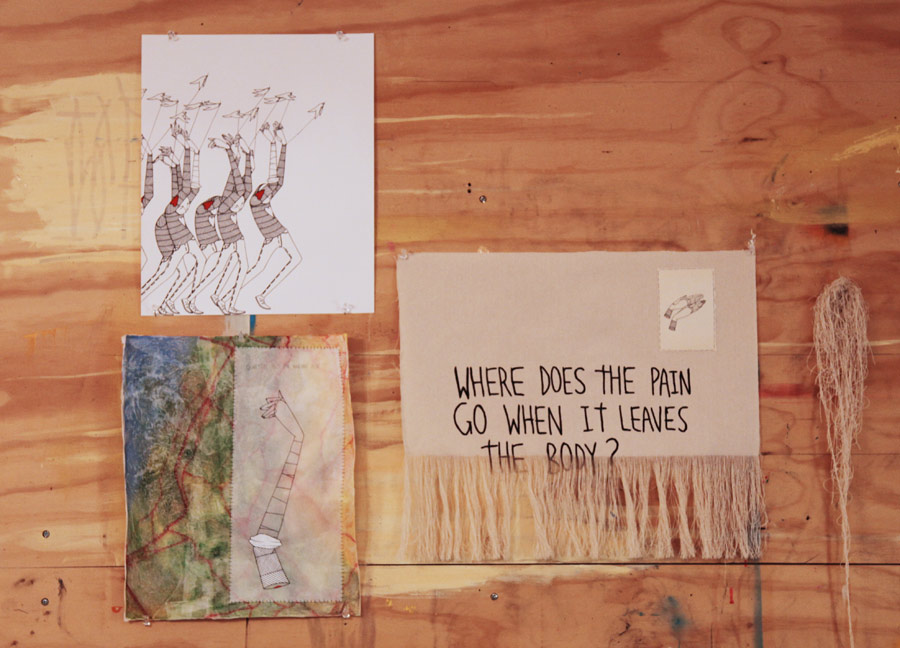

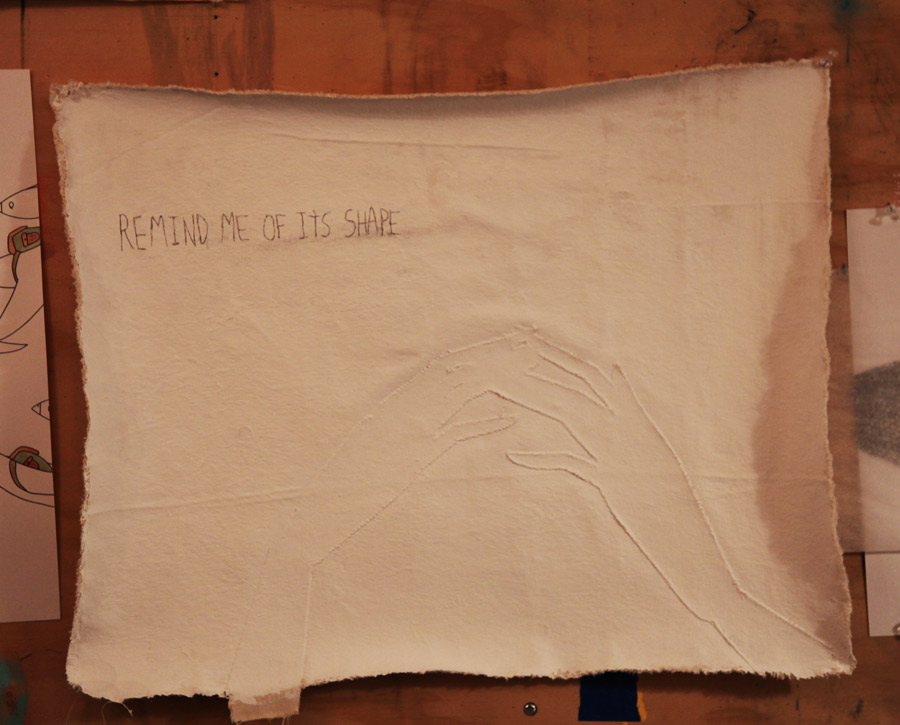

Carlos Ramirez. Bedstuy Art Residency. Februray 2018. (photo © Jaime Rojo) “I just take it from life and the shit I hear. Like the first day I got here there was this guy out of the street on the phone and he was saying ‘shit don’t cry don’t cry shit man.’ They’re kind of like human artifacts.”

Looking at the eye-popping bright colors that wash across his canvasses, he observes, “A lot of us go through this thing where we have learned not to be sensitive to things around with us, just do what you gotta do. It’s survival and suffering and the colors are just to get past it – to laugh at it.”

“I grew up with my mother where we would eat beans for like a month and we got through it and we still had happy times. And I’m not kidding, a lot of my family, when they got here, they would eat the armadillos in the street! They’d actually eat that shit and they were laughing – and who knows what else.”

Carlos Ramirez. Bedstuy Art Residency. Februray 2018. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

Are the difficult memories something that a person can move on from? “I don’t know maybe I’m still kind of healing from that shit because we went through some hard times and maybe that’s why these (figures) are kind of dark. I mean they are always dark but I see what you see. But I don’t know – it’s like something still needs to be said.

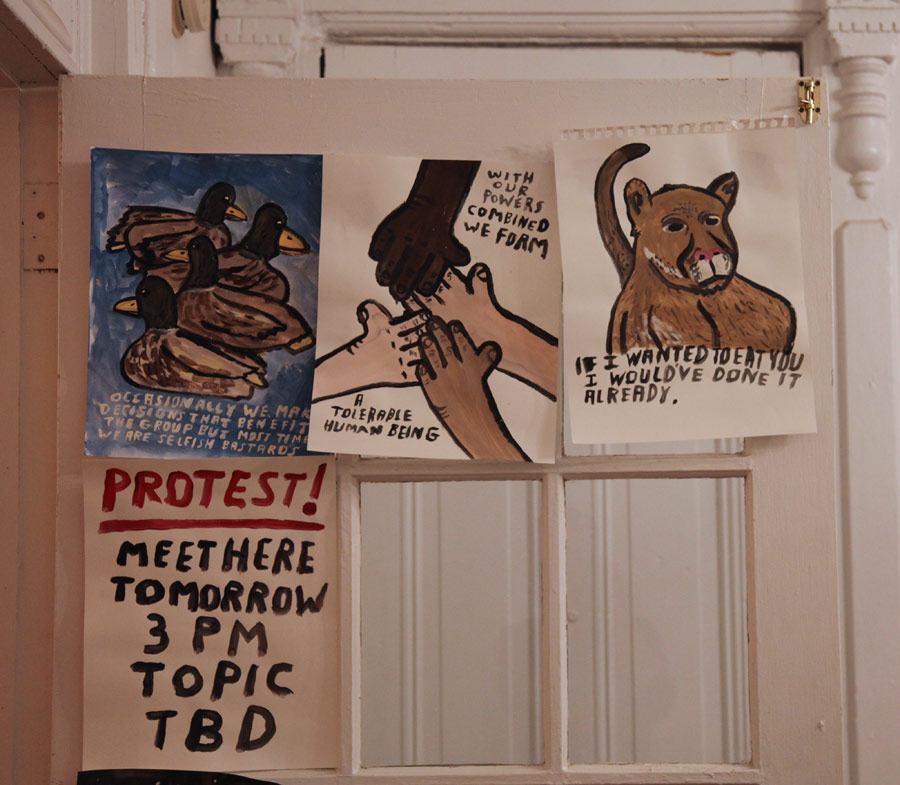

An activist at heart perhaps as a result of having people like his mom as a role model, Carlos looks at current political and social events and searches for ways to help the community. We talk about the DACA immigration program in the US that allows children brought to the country by parents who were not citizens to stay, known as Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. Since Trump took office, the DACA program has been under attack.

Carlos Ramirez. Bedstuy Art Residency. Februray 2018. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

“Yeah I find it so hard to ignore that shit because I feel that sense of urgency because you’ve got to say something. Like I don’t know if I say it enough.”

His advice to DACA kids sounds like the champion of the underdog that he says he is, giving advice that in some way applies to himself as well; from a perspective of a lifelong and wizened fighter.

“I think I would want to say to them that there wouldn’t be a DACA movement if they hadn’t done what they have done. So never give up, you know? You know everything, unfortunately, is gradual sometimes and its in small battles – but it’s a big war. It’s kind of like racism – like I think there are some other people we need to deal with their attitudes and find out why they need that shit.”

“But I think, ‘Never give up. Ever, ever, ever, ever.’ “

Carlos Ramirez. Bedstuy Art Residency. Februray 2018. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY