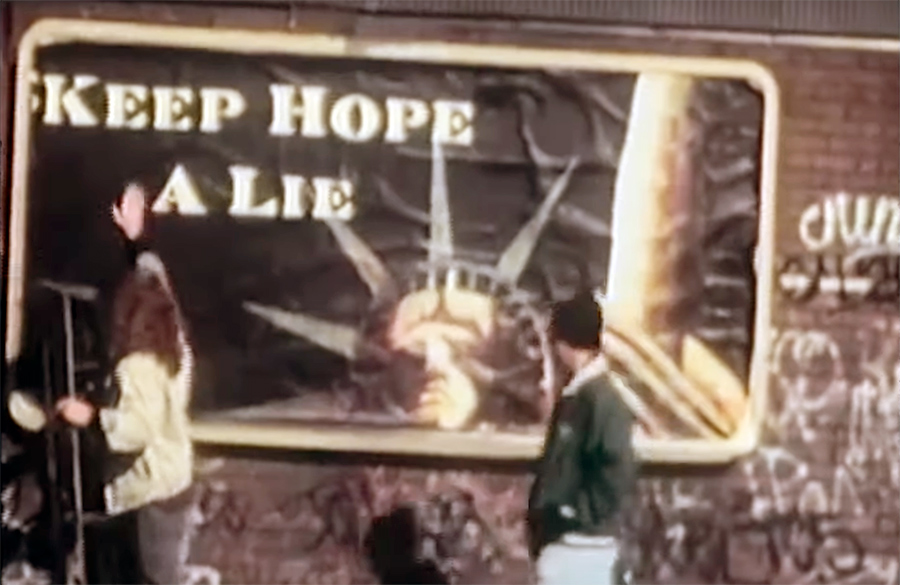

Long before he hijacked billboards, Ron English was growing up in Decatur, Illinois, tuning in to the everyday spectacle of ads and authority—and wondering why nobody was messing with them. By the late 1970s, English had begun altering billboards in Texas, driven by the realization that “making art was only half the equation.” The other half? Being seen. Advertising billboard culture became his unwitting canvas, a visual battleground where commercial power collided with public resistance.

From satirical cereal mascots to twisted cartoon icons, Ron English has consistently lampooned consumer culture, branding, and the corporatization of childhood. His warped advertising parodies echo an earlier tradition of subversion—perhaps most notably the Wacky Packages stickers of the 1970s, illustrated by artists like Art Spiegelman and Norm Saunders. These collectible cards spoofed products like “Cap’n Crud” cereal and “Crust” toothpaste, offering kids a gleeful way to question the slick promises of mass-market brands.

Alongside MAD Magazine’s fake ads, they helped cultivate a generation that cast a suspicious eye toward the messages pumped out by powerful corporations—corporations Ron would later stick his fingers in the eyes of, quite literally, on their own billboards. But beyond the pop surrealism lies a deeper urgency: the struggle over public space. As English notes, “Why should a company own a million billboards—and I own none?” It’s a question that resonates in a world where corporate entities can buy influence and visibility, while ordinary people are largely shut out of the conversation.

Street art and billboard takeovers in particular respond to that imbalance. They are risky, illegal, and often thankless acts of defiance. English’s work—sometimes carried out in daylight while wearing a reflective vest to pass as a worker—subverts not just the medium but the system that controls it. His collaborations with activist groups marked a turning point: art for art’s sake gave way to art with a message.

This video and interview by the next generation of political artist-activists, INDESIGN, pays tribute to English—not to glorify him, but to understand his path and purpose. His story helps illustrate why artists still take to the streets: not always for fame, but to reclaim space, to question authority, and to be heard in a world flooded with noise.

Other Articles You May Like from BSA:

Our weekly focus on the moving image and art in the streets. And other oddities. Now screening : 1. Petro Wodkins makes Putin Sing and Explode: Sound Of Power 2. PangeaSeed's Sea Walls....

It's when you have an opportunity to see a piece of art on the street in person. The combination of portraits, graphic design, and text treatments may spring more from the imagination of those in the...

GOAL! Call it the ‘World Cup Effect’ as your daily news features rousing updates about wild eyed athletic men kicking a ball on a grassy plane in Russia. How this impacts your day, one cannot be su...

Our weekly focus on the moving image and art in the streets. And other oddities. Now screening : 1. ONO'U Tahiti 2017. A video re-cap by Selina Miles 2. Private View: Ian Strange via Nowness 3...

Our weekly focus on the moving image and art in the streets. And other oddities. Now screening : 1. Richmond Mural Program 2014 2. Black ANZAC: Time Lapse of WW1 Soldier Wall 3. Adnate, Aske...

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY