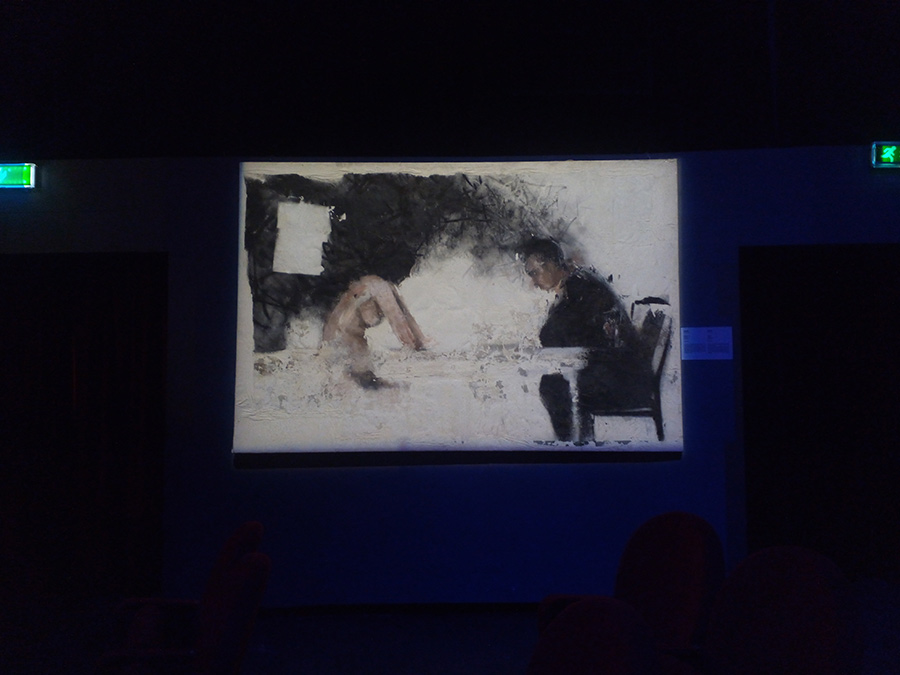

Borondo buffed his own work. It happens occasionally, not often.

Rarely inside an exhibition.

In a defiant act to reclaim the right to authorship and deny ownership and profit-taking, the Spanish graffiti writer/ street artist/ muralist/ fine artist is saying publicly that he, or one of his agents, has defaced his own work in an exhibition that is charging an entrance fee in Turin, Italy. The work in question, according to Gonzalo, was ripped out of a wall in an “abandoned” place by restorers who “claimed to be non-profit.”

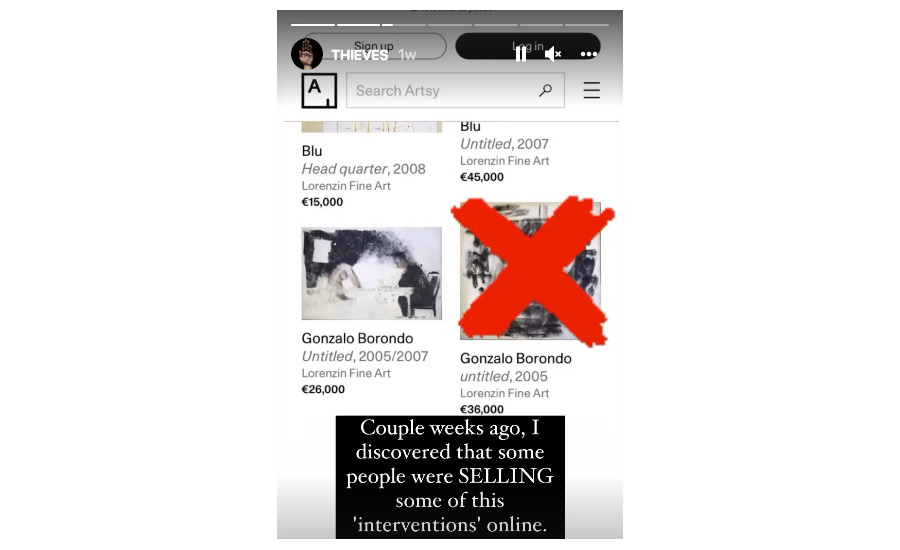

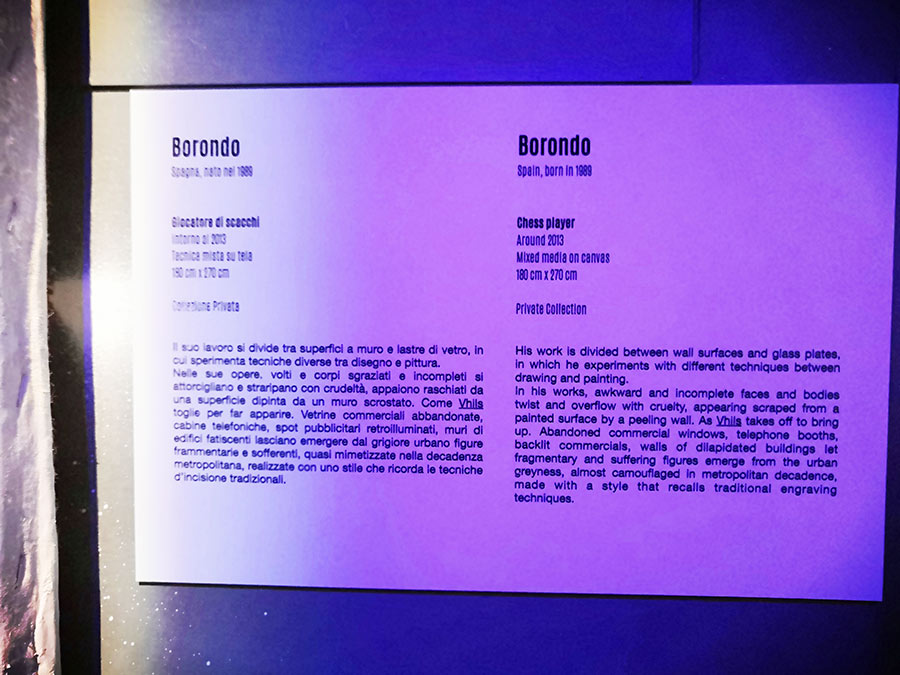

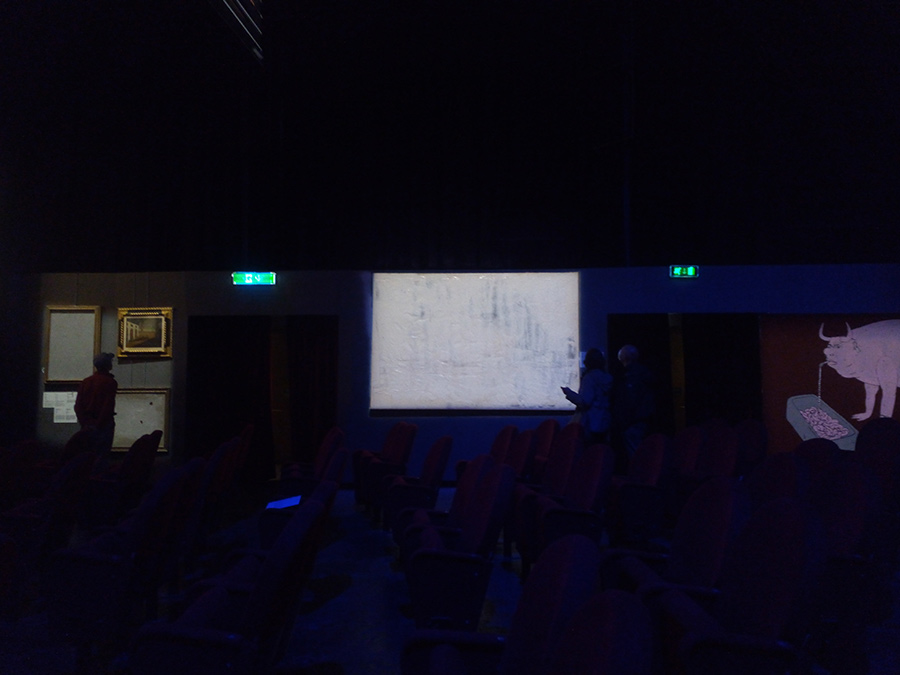

Not so, says the artist, who discovered some of the works for sale later on Artsy.com, and he posted about it on his Instagram stories. He also learned of one piece being shown in a commercial exhibit that opened in June called “Street Art in Blu 3” in the foyer to the auditorium at the Colosseo theater in Turin. Boasting 150 works by 36 artists, the ticketed show promised a spectacular experience and works by artists like Blu, Banksy, and 3D.

That was not what he had planned when he painted the originals in their location-specific installations, says Borondo in an email. “These interventions in public space weren’t made with the intention to create objects to consume, but to dialogue and accompany their surroundings,” he says.

“Without their context, the interventions make no sense, the will and the intent of the artist have disappeared, so, in the end, the artworks don’t exist anymore,” he continues.

True enough, but once an artist has created a work, no one will ever be completely able to control how it is interpreted, how it is used – it may even be destroyed or integrated into other works by other artists – regardless of the original ‘intention’. Piss Christ by Andres Serrano used a religious icon never intended to be employed that way, Duchamp’s “Fountain” urinal was originally intended to be, well, a urinal, and Hirsts’ shark in formaldehyde doubtfully was intended to be used as someone’s private art by the Creator, or by the shark.

People are even now debating if any of those examples we give above make sense, or are ‘art’ – especially after their transformation or removal from their original context. But we get Borondo’s larger point, and even more, we understand his interest in deleting the image from a ‘for-profit’ carnival show like this one appears to have been. At the very least, a presentation of his work in this context detracts from his carefully built reputation as an artist.

The larger debate is still raging. Who owns street art – installed legally and illegally. What are the implications and limitations of intellectual property, and physical property? What is the role of documentation, or preservation – in light of the artists’ intention and the greater edification of future generations? And at which point is it worth fighting for, or about? We expect to hear these arguments for years to come.

Here is a video of the action courtesy of the artist.

Other Articles You May Like from BSA:

Welcome to BSA's Images of the Week. In the past two decades, Asbury Park, New Jersey, has undergone a dramatic transformation, evolving from a struggling, economically challenged city into a ...

Among the various events at this years’ Miami madness called Basel were the multiple projects that intersect with Street Art in the Wynwood District. Walls of Change brought new large scale murals and...

In the heart of the Emilia Romagna region, close to Ferrara, a new mural brings a favorite cinematic moment to life. Towering on a wall as part of the "Gherardi città del Cinema project," it showcase...

As you would know if you waited in the dark out in the open night for a freight train to paint, the earth vibrates and the rumbling can raise adrenaline levels with fear and excitement, and anticipat...

Did you see that movie Words and Pictures? A bit sappy and chock-full of 1st world problems, but some good acting and an underlying premise that has been argued for centuries; The battle between the p...

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY