The Ljubljana Street Art Festival 2021 took place as a cultural festival this year in the capital of Slovenia with painting, lectures, panels, special events, and guests like street artists Escif, public installation artist Epos 257, cultural instigator/commentator Good Guy Boris, and global graffiti/street art documentarian and photographer since the 1970s, Martha Cooper.

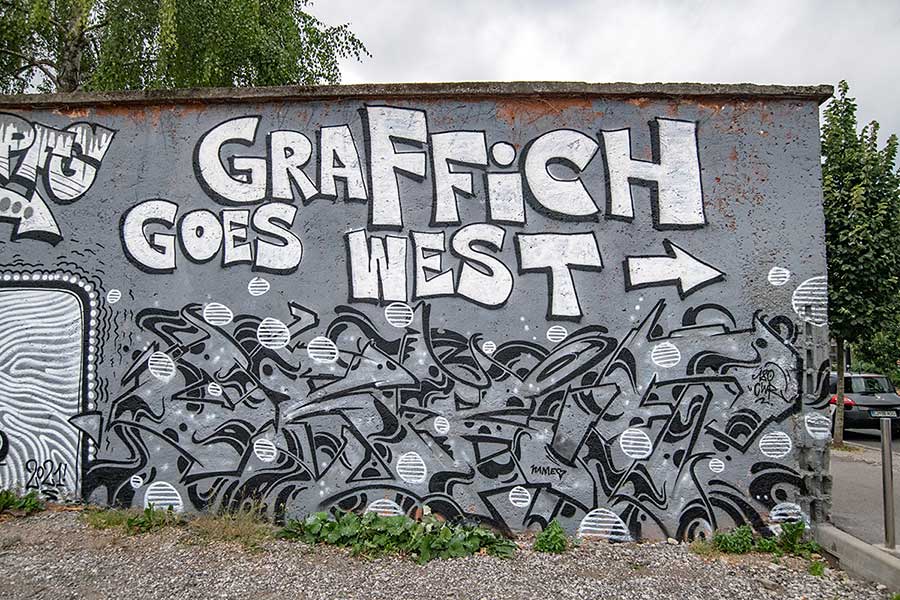

A unique event during this year’s festival included graffiti and street artists of various hand styles and influences crushing walls in monochrome. “The Left Over Graffiti Jam will give a chance to empty the leftover spray cans and hand the walls over to new generations to add to the layers of paint and subculture,” said the program’s description.

Based on the format of a graffiti jam, artists were invited to a series of walls to create while friends and fans set up impromptu picnics, parties, and took photos. The primary link between them all was their limited paint palette of whites, greys, and black paint that was allegedly “left over”. A historic place for many, this time the Hall of Fame was largely given over to new artists, aspiring writers, the new kids on the block. Whether it is still appropriately called a subculture or just “culture”, there is no doubt that the scene thrives on fresh blood and fresh paint.

The result brought more direct comparisons between styles and mastery – enabled by forcing artists to basically use the same materials for public expression. As an audience, you get a true sense of the writer’s personal style and poles of gravitational pull.

Luckily for us, Ms. Cooper shares her exclusive photos of the event here with BSA readers, while we speak with Sandi Abram, a co-founder of the festival with Anja Zver and Miha Erjavec.

A scholar and historian, Mr. Abram also gives us some context of graffiti here in the Balkans and helps us to position the significance of this festival.

BSA: Is there a history of the practice of graffiti and street art in Slovenia and specifically in Ljubljana? Or is it relatively new?

Sandi Abram: In Ljubljana, graffiti have a long history, beginning with World War II. During World War II, the territory of present-day Slovenia was occupied by German, Italian and Hungarian troops. The occupation of Ljubljana dates back to April 1941. The city was divided between Germany and Italy with barbed wire, roadblocks, military bunkers, machine gun nests and minefields.

In response to these events, the Liberation Front was formed. From 1942 to 1945, graffiti was used by individuals, various organizations and authorities as means of expression and as a reflection of socio-political events.

Soon after the occupation of Ljubljana, the so-called resistance graffiti by activists of the Liberation Front appeared on the walls. The first mass graffiti appeared in the shape of the letter V, short for “victory”, as a message to the occupiers that they would be defeated. Other symbols included the acronym for the Liberation Front (“OF”) or the stylized Triglav mountain (Slovenia’s highest mountain). The activists used numerous techniques to leave their mark on the occupied city, such as paste-ups, sgraffito, acid on shop windows, stencils, etc. I refer to these forms of expression as street art before street art; the techniques and strategies were a creative way to confront hegemony, a weapon of the weak, if I use the expression of anthropologist James C. Scott.

From this period, we also know of the so-called collaborator’s graffiti in the form of posters of Mussolini and the Italian king, leaflets also appeared on the streets occasionally. A particularly famous symbol of collaboration was the black hand with which the secret military units confronted the Liberation Army activists.

After the liberation of Ljubljana, post-war graffiti glorified leaders (e.g. Tito, Kardelj, Stalin) and the army (e.g., “Long live the Liberation Army!”). The symbols of communism (sickle and hammer) and praise for the Soviet Union (USSR) as representatives of the revolution and military allies were very common.

Graffiti as a predominantly leftist medium reappeared in socialist Ljubljana in the early 1980s as part of the punk movement, alternative subcultures, and sub political groups. This was also the time of coexistence between political graffiti and more sophisticated subcultural graffiti. On the one hand, punks sprayed “Johnny Rotten Square” to reappropriate space. On the other hand, fine arts students used graffiti as an alternative medium to paint canvases and the interior walls of underground cultural venues.

Finally, after a group of activists and independent artists occupied the former barracks of the Yugoslav People’s Army, today known as Metelkova, in the early 1990s, the first public and legal wall slowly emerged as a field of experimentation for new generations of budding writers. Today, the Metelkova City Autonomous Cultural Zone represents a cultural, artistic, social and intellectual hub where one also finds the Hall of Fame.

In the early 1990s, local artists incorporating the medium of graffiti started to emerge, an example being Strip Core. In more recent history, graffiti crews have left an important mark in the local public space, including ZEK Crew, Egotrip, 1107 Klan, Animals, and writers such as Vixen, Whem, Lo Milo, Rone84, and Planet Rick. Contemporary street artists who emerged from this scene include names like Danilo Milovanović, The Miha Artnak, Nataša Berk, Veli & Amos, Evgen Čopi Gorišek, Sad1.

BSA: We have talked previously about how your festival focuses on content, not on bringing in a dozen big-name artists just for the sake of having big names on your line-up. Why is this important to you?

Sandi Abram: Through LJSAF, we bring together international and local artists and scholars. The Programme Committee, which included me, Anja Zver, and Miha Erjavec, designed the festival events to encourage visitors to read the streets and participate in various activities.

For instance, the mission of the alternative tours and the street art conference is to interpret heterogeneous urban spaces, to explain the actors in the public space, the artistic and creative inspirations, the social struggles, to recognize and decipher ideologies of intolerance. So it is not only about producing the “text” (a mural as a thing-in-itself) but also sensitizing the public about the “context” of street art, i.e. the micro-location in the urban space. It is hard to understand a city if you do not “read” the screams on the walls – already the philosopher and sociologist Henri Lefebvre said that graffiti best illustrates the contradictions of contemporary society. They point out what is tolerated, what disappears.

Content co-creation is another important dimension of LJSAF. The festival events not only showcase young, emerging generations of street artists and scholars, they also provide a space, a productive crossroads for them to meet and collaborate. And for us, that is exactly the purpose of the festival’s art residencies, exhibitions, and graffiti jams. In short, street art is not only about big names, but a broad stream of unknown and underground creative minds joining forces.

“The festival events not only showcase young, emerging generations of street artists and scholars, they also provide a space, a productive crossroads for them to meet and collaborate.”

Mitja Velikonja

To learn more about Ljubljana Street Art Festival click HERE

Other Articles You May Like from BSA:

About a hundred years ago "fascist" was commonly used to describe authoritarian movements, such as Hitler’s Nazi regime in Germany and Franco’s rule in Spain. Mussolini was considered a socialist fir...

Innovative artist in the public sphere, Daniel Weissbach aka DTAGNO aka COST88 has charted new territory many times with his hand made experimentation that makes graffiti and street art search themse...

New York is gearing up for a deep freeze from the weather and Donald Trump's inauguration this weekend. With 100 Executive Orders reportedly queued up for him to sign, the forecast for the next f...

Uh-oh, looks like Jonathan’s stumbled onto something. A wild mushroom on a tree in the Enchanted Forest perhaps? A half-full dime bag on the deli floor? The contemporary art worlds Next Great Artist?...

A worthy companion to the original tome, Bjørn Van Poucke and Lanoo publishers extend the hitlist of favored muralists that he & Elise Luong began in Street art/ Today 1 - and the collection is u...

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY