A quarter of a century since falling in love with New York, WK looks at his route.

WK Interact was 8 years old, spending hours drawing on old floor plans. On the job with his father, even then he buried himself in his work while Dad rushed around giving orders at his interior design worksites in the south of France. A few years later, his drawings came alive with movement as he hung out all day in dance schools watching young bodies fly across the floor. Once more his style catapulted forward the day he discovered how to stretch and animate a figure just by dragging it across the glass of a photocopier. Action. Captured.

Without question, his love of the street, of art, and wild motion fully materialized and went on steroids when WK first laid eyes on monstrous, convulsing New York City. He was 16. He was blown away, frightened, and excited. Two years later, he gave into the magnetic pull of New York’s raw power.

“I remember I went downstairs and I said to my parents, ‘You know what, I am going to New York’, and my parents said ‘But why, what for? Are you going to be able to get a good job? Why do you have to go to a place where you don’t even speak English?’,” he remembers. A great struggle took place but he left for the United States anyway, alone for the first time. That’s when WK’s war began, almost a quarter of a century ago, on these streets. And he won.

If his work on the street is an indication, it has been a constant state of war. Look at these images and themes that reappear in WK’s work since he first came to New York; Ever-present fear, violence, anxiety, overheated sex-play, fishnets & firearms, contorted figures racing, martial arts kicks to the head, hand-to-hand combat, boxers swinging, prisoners tied and bound, hooded figures snapping heads of bound businessmen, terrifying escapes in progress, maniacal twined and twisted forms and faces, propaganda, undercover spies, official seals, gun assembly diagrams, digitized labels, ID fingerprints, cameras, surveillance, camouflage, radioactive symbols, streaming codes and bureaucratic text passages, black military choppers hovering overhead, contorted soldiers screaming “bring me back”, a permanent state of survivalism… All of these hellacious visions collide and collapse and expand in continuous motion and interaction almost exclusively in black and white in wheat pastes, paintings, screen prints, photographs, sculpture, and performance installations on the street.

You may think that some of this work is vaguely autobiographical, but for WK, all of this work is simply a reflection of the city he chose and the atmosphere here. “New York is extremely demanding and challenging”, he says, “If you do something sexy in the street in New York you are in trouble. If you do something violent, people will give you the thumbs up!”

In other words, he’s playing to the audience in this particular city and unfortunately it may give an inaccurate impression of WK, the person, “I’ll just say this; My work, the people always see one thing – fear, attack, violence. They have absolutely no clue of the other side. I don’t think they are ignorant. My work is very black, it’s very bold, it’s very graphic, it’s very strong. There is nothing really friendly like a little bird flying around or a pink piglet… it’s totally not that. But I live in New York City and I am responding to that kind of contrast. The weather is very strong, very hot and very cold. All the traffic is heavy, the structure of this city is almost like a double bladed knife. I wanted to adapt myself as a New Yorker and adapt my mind as an artist. I’m always fascinated by this fear, and the people who want to ignore it.”

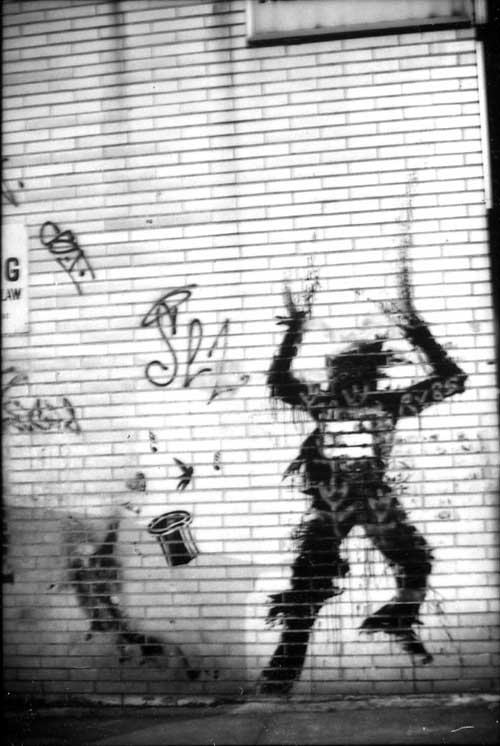

It was the mid-1980’s and there was not such a thing as “Street Art” yet, but “Low-brow” was in full effect, with graffiti as a new darling in the booming art market. The City had just pulled out of a deep recession, Wall Street wall was flush, newly minted “Yuppies” were ordering sushi and flashing their Swatches, Run DMC was rocking a tricky rhyme, and graffiti had been nearly scrubbed from all the subway cars. Kenny Scharf took his cartoons into the Tunnel, Richard Hambleton was doing shadows on the street walls in the Village, Keith Haring was doing his thing in the subways, and Warhol was fixating on Basquiat.

Image of Richard Hambleton shadow work by photographer Allan Molho

WK Interact knew very little about all of this activity, but he gradually learned. 18 year old WK looked for work as a graphic artist but because he spoke little English and had few connections, doors slammed in his face quickly one after another. Eventually he got work as a carpenter and painter, living in a tiny room on Houston in Alphabet City.

The Lower East Side was his first real school; “I was like a student. I was not that good in school, and all of that work, work, work to get a diploma! That diploma was absolutely no help to me. My own diploma was my own dream, it was my own need. It was not proving anything to anybody, just me.” What followed was the “School of Hard Knocks”; occasional opportunities, a lot of drawing and time alone observing city life and street life, experimenting with his work on the street, and missteps that included a period actually living on the street in a box. Socially, he wasn’t able to connect with other artists and couldn’t really understand how to navigate the city and street culture world he had thrust himself into. He spent a lot of time feeling a deep sense of alienation.

“When I started to do my stuff I was so ‘not there’. I was so different and without an understanding of the art, the graffiti, the branding. Nobody really understood me; I was a bit early to be put in this category so I created myself just to be “this guy”. There were groups there, but I was on my own. And it was very, very difficult to believe in myself. It was so difficult not to be a part of a group. It was so difficult not to be able to speak English. I used go seek artists because I liked their work, and they never replied, or never wrote back.”

While WK still values those hard years because his inner strength and knowledge of humanity and inhumanity was greatly broadened, not to mention his development as an artist, he wouldn’t recommend them to you as a friend, as those years haunt him today. Coupled with feelings of rejection from his parents, this sense of alienation made him a lone wolf in a hostile town.

A turning point for WK may have been the literal turning point of the corner of Prince and Lafayette streets in Soho, a garage and mechanics business. WK liked the multiple surfaces and angles of the lot, as well as their industrial rawness and he inquired about who owned it. After cajoling the owner of the garage to allow him do a piece on the wall, he eventually went on to “run” that whole corner that was a mechanic’s garage for a number of years. He likes to say no one noticed the racing, leaping, landing, crashing, chasing, panicked people in black and white on that block for many years, but in fact many New Yorkers around at that time still remember the sudden surprise of those images on the buildings and began to look forward to checking them out in when they passed through Soho.

A piece on it’s larger overhead walls one time featured model Alek Well – a bicephalous blur portrait of gut-busting joy and ebullience as one head is tossed back to the left and one slightly forward to the right, anchored by solid shoulders. The scenes and players changed but usually the entire space was a spooked by hair-raising scenarios which you may or may not want to understand more clearly.

Similarly many people remember as “classic” the view of WK’s iconic 2-story speeding rollerblader racing along a building on the southwest side of Houston street to jump across Broadway. To hit one of his spots in it’s context is to experience a sudden pick-up in pulse, or skip in the beat, and a little bit of confusion that sharply torques the wild energy of the urban environment. No one else endeavors to shake you like this. It’s safe to say that you admire the mind of the artist who brought you this jolt.

He lived frugally in a tiny studio and brought home left-over paint from his day jobs. It was pretty early in his career that he decided black and white paint was the best way to portray New York and it’s brutal contrasts. “If I go back to my country I will begin to paint blue and pink,” he explains.

Suffice to say, it’s been a long, arduous climb and not one he likes to speak about for a long time, understandably, but eventually WK Interact found his way in New York, and London, and Paris, and Italy, and Sydney, and Japan…. With labor, persistence and luck one opportunity turned another. He doesn’t appear unduly proud that his work today is in demand. He is thankful that he shows in respected galleries, is featured in articles, videos, and he is continuously on the move.

When looking at the rough times, he says, “Those limitations created what I did. That made me want to reverse it, to upgrade it – so I made myself do more. You can see the force in my work, that constant motion, the face. It is on the move, you can see the actual thing vibrating, and this has been my position, and it has been like this for the last 23 years. As far as what happened to me coming to the States, I don’t wish this for anybody. I think this was painful, and it will always be painful.”

Part 2 of this inteview continues here

1980’s New York Street Life (the MTV version) with Run DMC in “It’s Tricky”

Other Articles You May Like from BSA:

Doug Gillen's New Video Captures "Homeless" Void Projects. "Homeless" Miami, 2019. (photo still from the video by Doug Gillen/FWTV) “The aim is to create quality shows outside of the convention...

BSA is pleased that we were able to help bring NeverCrew to the US along with FatCap to realize this huge Mexican Grizzly on a celebrated wall in Arizona. "El Oso Plateado and the Machine” is the lat...

Box trucks are a favorite canvas for many graffiti writers in big cities and have become a right of passage for new artists who want the experience of painting on a smooth rectangular surface that bec...

Our weekly focus on the moving image and art in the streets. And other oddities. Now screening : 1. Fintan Magee / Nothing Make Sense Anymore / A Selina Miles Film2. Aufstieg (Rise) by Eginha...

“I surprised myself with the patience I had,” Olek tells us about the arduous bureaucratic game of waiting and preparing that she and her team played to get this big phallus up in Santiago de Chile fo...

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY