Street Artist Uses Art Installations to Study History, distant and close.

This scene depicts Jane McCrea, a British loyalist who was engaged to a man in the British army, who was captured by two Native Americans (photo © General Howe)

Street Artist General Howe participated this fall in an art/history show at Skidmore College by doing a site specific installation in Saratoga Springs, New York. The project; “Saratoga Smackdown: The Expendable Jane McCrea and the Soldiers of Fortune” consisted of a series of installations showcasing the 1777 “Battle of Saratoga” on a farm in the Adirondack Mountain region. According to historical accounts, Jane McCrea, a preachers’ daughter, was killed during a perhaps botched hostage-taking, and her death was used for propaganda purposes to enrage locals to enlist with the Patriots against the British.

As with his street pieces the General’s unusual approach to this outside environment and his choices of materials can call into question an observers feelings and perceptions of historical events, war history, and their relative meaning. Usually warriors are depicted in public space by grand and substantial sculptures of mountainous scale, adding to the perceived heroism of the actor depicted. General Howe miniaturizes the size and sometimes simplifies the rendering to merge with the memory of a child’s imagination and concomitant exaggerations, where many are encouraged to ‘play’ war. The Street Artist frequently refers to his own childhood and the endless hours of play in nearby woods with his multiple war toys.

As with his street pieces the General’s unusual approach to this outside environment and his choices of materials can call into question an observers feelings and perceptions of historical events, war history, and their relative meaning. Usually warriors are depicted in public space by grand and substantial sculptures of mountainous scale, adding to the perceived heroism of the actor depicted. General Howe miniaturizes the size and sometimes simplifies the rendering to merge with the memory of a child’s imagination and concomitant exaggerations, where many are encouraged to ‘play’ war. The Street Artist frequently refers to his own childhood and the endless hours of play in nearby woods with his multiple war toys.

“The Death of Jane McCrea,” oil on canvas, by the American artist John Vanderlyn, 1804. Courtesy of the Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut.

Below are excerpts from General Howe’s experience and from the project’s statement:

“The Battle of Saratoga occurred in September/October of 1777. 2 battles occurred, the first was a draw and the second was won by the Americans. The Jane McCrea incident was a Pearl Harbor/9-11 incident of the Revolutionary War. American media propagated it to increase enlistment into the war. Though not an explicit point in the project, this incident also illustrates the deceiving treatment of Native Americans by the “white man”, in this case the British. The terror these Native Americans brought was much scarier then anything we hear about today.

In preparation for the project my research on mercenaries brought me to the company formally known as Blackwater, now Xe Services LLC. According to many news accounts, they were hired by the US Military as contractors to provide various services in Iraq during the war. One of the main jobs they had was security for important peoples traveling in Iraq. There are reported incidents where these “security agents” opened fire on innocent people, causing much controversy. On the flip side there were incidents where members of the organization were caught off guard and were horribly killed. The multiple incidents eventually led to the Iraq government canceling Blackwater’s contracts to work in Iraq.” ~ General Howe

Americans in battle with Native Americans (Photo © General Howe)

As is customary and expected for General Howe and other historians, parallels are drawn between those events and the wars the US is currently conducting in The Middle East. It’s one thing to pose historical plastic soldiers around to commemorate a long ago event with people who have long been dead, as well as their loved ones, their politicians, religious leaders, and their captains of industry. This mornings’ free paper that they hand out at the subway entrance contains a special tourism section on Colonial Williamsburg, Va., featuring a misty glowing snowflake inflected photo of “re-enactors” dressed in uniform with “historically accurate” weapons in hand. When depicting war scenes of contemporary times, this art can be much more difficult to encounter, especially if you didn’t pay to get in. Perhaps because of the scale and it’s direct connection to current events, the installations can even inflame a viewers’ passions.

General Howe describes this scene as a contemporary middle eastern building with insurgents and military contractor soldiers (photo © General Howe)

In this piece General Howe refers to news accounts of an event during the Iraq war where military contractors were hung and their bodies were burned publicly. (photo © General Howe)

An overview of the art installation at one of the galleries on campus (photo © General Howe)

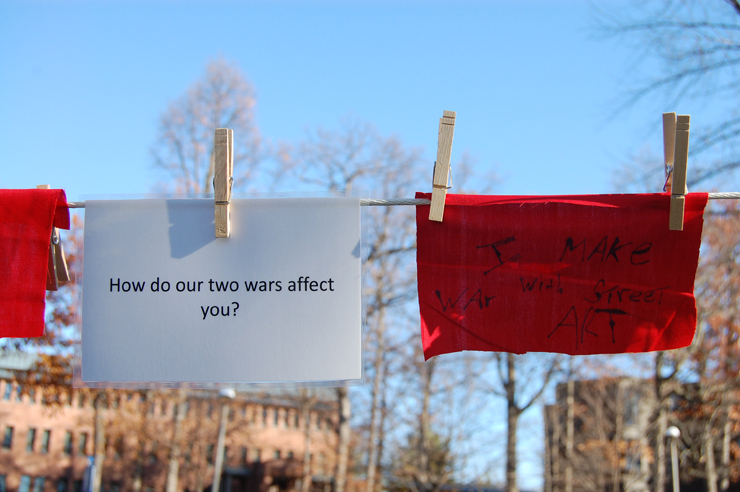

“While I was on this journey I captured images of other interesting things going on at the school, anti-war projects, graffiti, and street art” General Howe

A wheatpaste of a squirrel carrying a tomahawk. (photo © General Howe)

A student project on campus questioning war gives a platform for the people to voice their opinion (photo © General Howe)

Other Articles You May Like from BSA:

New York is bittersweet as we are welcoming summer this weekend and remembering those who served and who were lost in war as well (Memorial Day); amidst a changing political atmosphere where the c...

In honor of the 50th Anniversary of the Stonewall Inn uprising in the West Village in Manhattan, we are giving the spotlight this Sunday to the many artworks that have been created by dozens of a...

There used to be over 600 lace-makers here. Nespoon is remembering them with her new works on the street. NeSpoon. Le Locle, Switzerland. July 2019. (photo © NeSpoon) Part of a residency that ...

Amidst the fusillade of news from the Middle East these days, you may have missed that the young people of Baghdad in Iraq have been demonstrating in the streets against the government. They are figh...

Tito Ferrara, potentially the first Brazilian street artist to create in Norway, and his assistant, swiftly executed a remarkable feat – crafting a composition of two powerful jaguars adorned wit...

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY